- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Exiles at Home is a fascinating work by a feminist of the 1970s about a group of anti-fascist feminists of the 1920s and 1930s. From it we learn as much about the world view of the author as we do about the politics of its subjects. A serious book, about serious writers, it examines novels for their historical rather than for their literary interest. It offers no real criticism of writing styles, and no comparison with modem feminist authors. Nor is it a book to be read in the hope of rediscovering almost forgotten characters from our literary past.

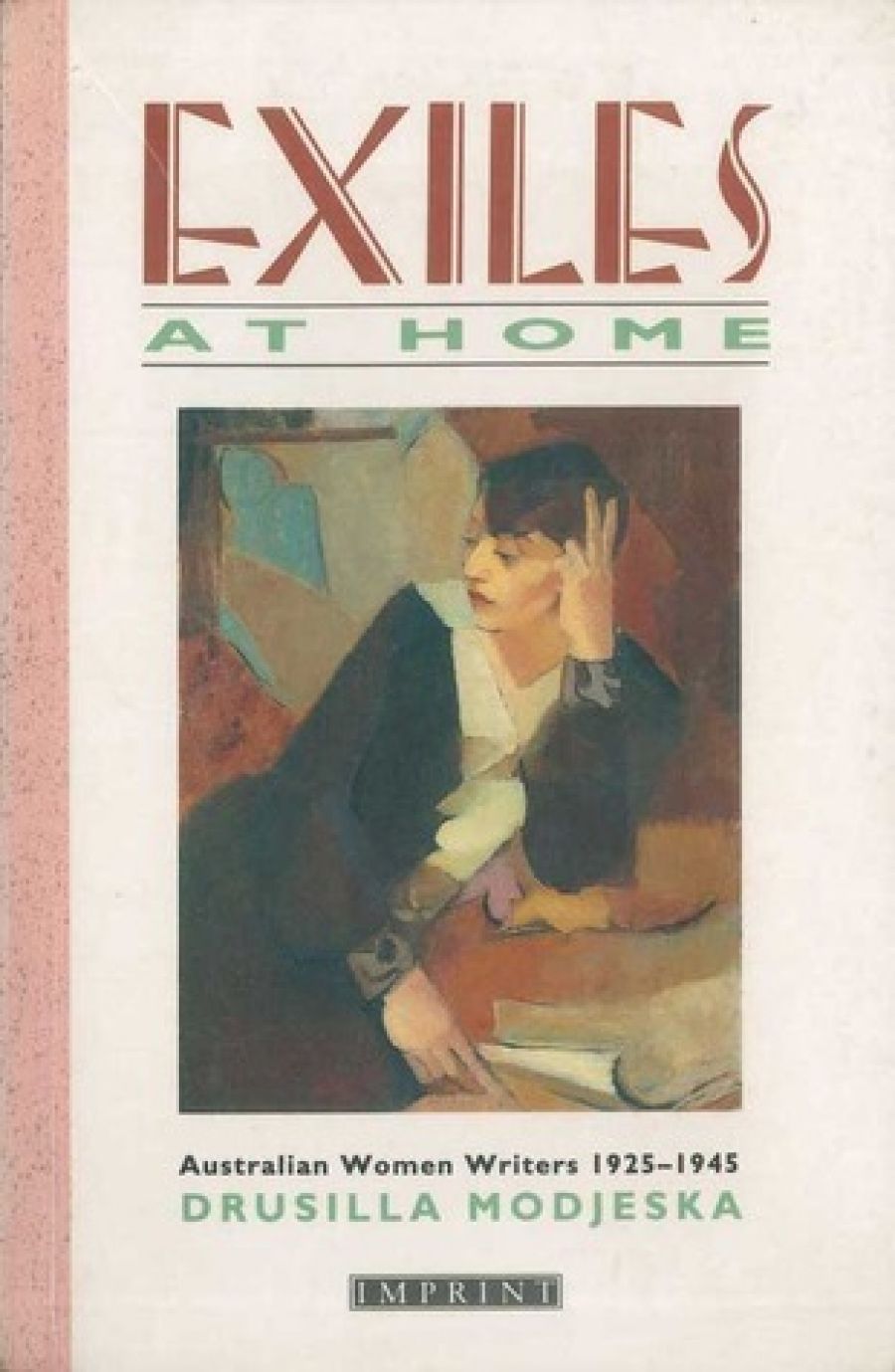

- Book 1 Title: Exiles at Home

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australian women writers 1925–1945

- Book 1 Biblio: A&R, $19.95, 283 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/PXG4q

One of the standard responses of classes, races, or nations that believe themselves to be culturally oppressed has always been ‘affirmative action’. Ten years ago among feminists this was called ‘positive discrimination’ and took the form of promoting all products of female artistic labour over those men, regardless of quality. Fifty years ago, Nettie Palmer, one of the few serious critics of novelist contemporaries, put it this way: ‘Our writers, of serious quality, are so few … we can’t afford to use one to knock another down even a bit.’

Nettie Palmer, whom Modjeska casts as the patroness of Australian literature, saw her work as having a dual purpose. Firstly, her private criticisms of their works would encourage and inspire novelists used to being ignored or patronised. Secondly, her public insistence on the healthy state of native artistic endeavour would loosen the stranglehold of imported culture on the public consciousness.

Modjeska’s unashamedly ideological reading of the texts leads her, too, to exaggerate the merits of her women writers. She devotes considerable space to novels (for example, Eleanor Dark’s Slow Dawning) and to authors (for example, Jean Devanny) which simply do not merit such scrutiny. Dark herself long ago disowned Slow Dawning, thus casting doubt on the authenticity of its characters, their responses and emotions. What to its author was a mere pot-boiler, remains interesting to Modjeska, ‘because, of these early novels, it alone offers a hint of collective political action by women’. Similarly, Modjeska exaggerates the worth of the novels of Jean Devanny, whose characters are rarely remotely believable. Non-feminist authors, such as Dorothy Cottrell and G.B. Lancaster, are beneath Modjeska’s consideration because of their silly and romantic plots. Yet Devanny’s plots are every bit as silly and romantic. Ideological overtones intrude so far into her novels as to make them positively laughable at times, such as in Sugar Heaven, where Dulcie thinks of ‘the need of a man for a woman ... a physical necessitous urge like food hunger, satisfaction of which meant clearer action for the class, clear heads, quiet bodies, better men’.

Kylie Tennant, to my mind the best crafter of the entire group, and the only one whose sense of humour survived her awareness of the corruption inherent in capitalist society is criticised as lacking punch. According to Modjeska, ‘her humour ... [operates] as a shield to avoid confronting the political implications of what she describes, and as a device to reconcile her characters to the acceptance of intolerable conditions which are shown as the outcome of their social and economic situations’. Yet of all the novels by women in this period, the one which remains as a vivid account of the victimisation of one class of Australians by another, is Kylie Tennant’s The Battlers.

The ideological constraints under which Modjeska wrote this book lead her to lecture both authors and characters of these between-war novels on what their responses should have been to the crises they faced. This is tedious but is offset by fascinating accounts of Miles Franklin in America, of the relationship between Vance and Nettie Palmer, and of the conflict in the life of Prichard between Party and artistic work. Modjeska is intensely aware of the problems facing women who try to produce works of art in ‘that still blue hour before the baby’s cry’. She skilfully contrasts the lives of Nettie Palmer and Marjorie Barnard, to illustrate her claim that from the point of view of an aspiring artist there was not much to choose between married drudgery and the life of a dependent spinster. The material on political conflicts within the Fellowship of Australian Writers is interesting, as is the tantalisingly brief glimpse of Norman Lindsay and the King’s Cross bohemians.

Modjeska has successfully created the impression of a group of women at the same time highly moralistic, increasingly anti-capitalist, emotionally and politically confused, with ‘very little theory’ but very many ‘political anxieties’. She calls for their work to be understood in the context of ‘a critical history of culture and politics in this country’. Modjeska herself has written a selective history of this period, leaving out of her consideration women who were not interested in questioning the position of their sex, or the existence of inequality and exploitation in their new country. Thus the excellent index, which abounds with references to progressive writers, is devoid of a reference to Mary Grant Bruce, that most popular and prolific woman writer. Norah and Jim and the eternally jolly Wally have always had, and no doubt always will have, incorrect politics, but I for one think they rate a mention alongside Coonardoo, Sybilla, and the Watson’s Bay Ferry.

Comments powered by CComment