- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Indigenous Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When I was a small boy in Hobart, my mates and I would often go down to the Tasmanian Museum after school; and one of the exhibits that interested us most was what we called ‘the human skeleton’. It stood in a glass case on the stairs, and it was only when we were older that we took in the fact that these were the remains of ‘Queen’ Trucanini, last of the Tasmanian Aborigines. There was no general notion abroad then that there was anything wrong with exhibiting these bones; but I remember a vague sense of unease – of being in the presence of something shameful. Such a sense exists in all of us; but there is no god so powerful as science in persuading men to suppress it.

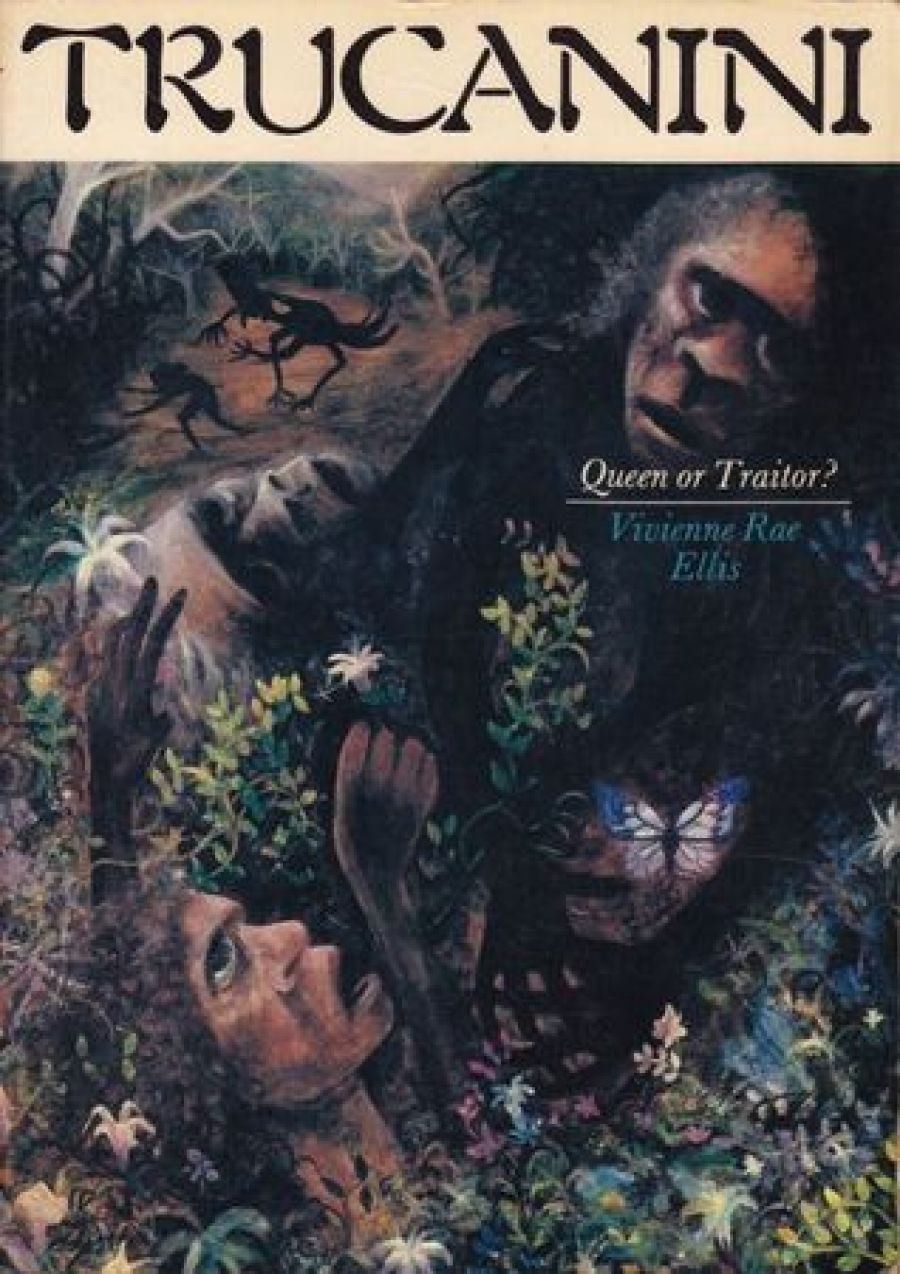

- Book 1 Title: Trucanini, Queen or Traitor?

- Book 1 Biblio: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 196 p., $9.95, $6.95 pb

Until I read Vivienne Rae Eilis’s moving and finely executed history, I didn’t know that Trucanini’s greatest fear about the disposal of her body had been disregarded. In her old age, she had been deeply troubled by the fate of her fellow-Tasmanian William Lanne, whose body had been illegally dissected by Dr W. L. Crowther. In the mid-eighteen-sixties, scientists all over the world were eager to obtain skeletons of the last few full-blood survivors of the Tasmanian Aboriginal race, and Trucanini was well aware of this. At the end of her book, Mrs Ellis tells how, at that time, Trucanini was taken fishing in the D’Entrecasteaux Channel by the Rev. A D. Atkinson, and how she suddenly broke down and sobbed. All her people were now gone, she told the vicar, ‘and the people in Hobart have got their skulls’. Then she knelt before him in the boat. ‘Oh father, father,’ she exclaimed, ‘bury me here. It’s the deepest place. Promise me!’

But despite the efforts of the Reverend Atkinson’s son, Archdeacon Atkinson, science had its way until 1976, the centenary of Trucanini’s death, when her ashes were scattered over the Channel.

European Tasmanians are haunted by Trucanini, and I doubt that anyone but a Tasmanian could have written her biography with such poignancy. Vivienne Rae Ellis is fast becoming one of the best historians currently writing in Australia, and this book is likely to become a classic.

‘Queen or traitor?’ This theme has aroused a good deal of controversy since the book’s first appearance in 1976. Some emotive and ill-informed comments have been made about it, including some that have suggested that Mrs Ellis was intolerant of her subject, and had somehow smeared her. Nothing could be Jess true; but what seemed to anger the lovers of stereotypes was the fact that Mrs Ellis had depicted Trucanini without sentimentality, but with absolute truthfulness – and also, I believe, with real sympathy instead of spurious emotion. The Trucanini who emerges is a vital, curious woman who was irresistibly drawn to the white men who had invaded her island – and who was, in the end, seen by her fellow Tasmanians as having betrayed them, however unwittingly. This was because of her remarkable association with G. A Robinson, the leader of the ‘Friendly Mission’ which brought the Tasmanians in to be delivered to their last home on the Bass Strait islands.

Mrs Ellis has drawn heavily on the gargantuan Robinson journals, as edited by N.J.B. Plomley; and in this she has done us great service. The journals do not yield a clear or compact account of the association, and Robinson’s references to it are cryptic. But by putting this source together with others, Mrs Ellis not only shows us what devoted service Trucanini gave Robinson (she saved his life on more than one occasion) but leaves little doubt that the two were lovers.

This startling contention is at the heart of Mrs Eilis’s story, which has all the elements of a good novel. It is not just Trucanini’s story/ but that of the little London bricklayer and lay preacher who was a genuine friend to the Aborigines but helped in the end to seal their fate.

He was contemptuous of the Black Line, and wrote to this wife: ‘What can be more revolting to humanity than to see persons going forth in battle array against the people whose land we have usurped?’ His concern to protect the Aborigines from the viciousness of the ex-convicts and seamen who preyed upon them was what drove him to per-suade them to come into safety: but in that safety, their true home gone, they would pine away.

And Robinson’s success plainly made him vain and ambitious; as his official importance grew, he saw less and less of Trucanini. One of the saddest moments in this account is his final farewell to the last remnants of the Aborigines on a visit to Hobart before his return to Europe, in 1851. He made no mention of Trucanini in his journal, and she did not travel with the other Aborigines who saw him off. Yet once she had fascinated him; and without her, he could not have succeeded.

Now she lingered in Hobart like a ghost, a plump little old woman pointed out as a queen – every one of whose subjects had vanished. She had never been a queen, and was not particularly virtuous; in Victoria, she was involved in a murder, and Mrs Ellis shows her in her youth deliberately seeking out the company of white men, and sleeping with those very convicts and whalers who had killed so many of her people, including her mother. Mrs Ellis believes that she instinctively knew then that her people were broken, stripped of the dignity of their tribal life, and consciously decided to cast in her lot with these white men, since the future of her island was in their hands. Whatever her character, there is little doubt that she was remarkable: a tiny human being of about four feet three inches, whose beauty, in her youth, no-one ever forgot, and whose realism and curiosity led her into a special and tragic future. Here is the real Trucanini, with all her frailties, pathos and courage. Vivienne Ellis has made her live.

Comments powered by CComment