- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Aviation was a myth still in the making to my generation of Australian children. We cricked our necks watching a patch of sky for Amy Johnson’s arrival and, indeed, whenever an aeroplane engine was heard aloft, as if the watching itself was a necessary act of will, or prayer, to ensure the safety of those magnificent men and women whose photographs showed them always ear-muffed, be-goggled and leather-jacketed, smiling and jauntily waving thumbs up to us their earthbound worshippers.

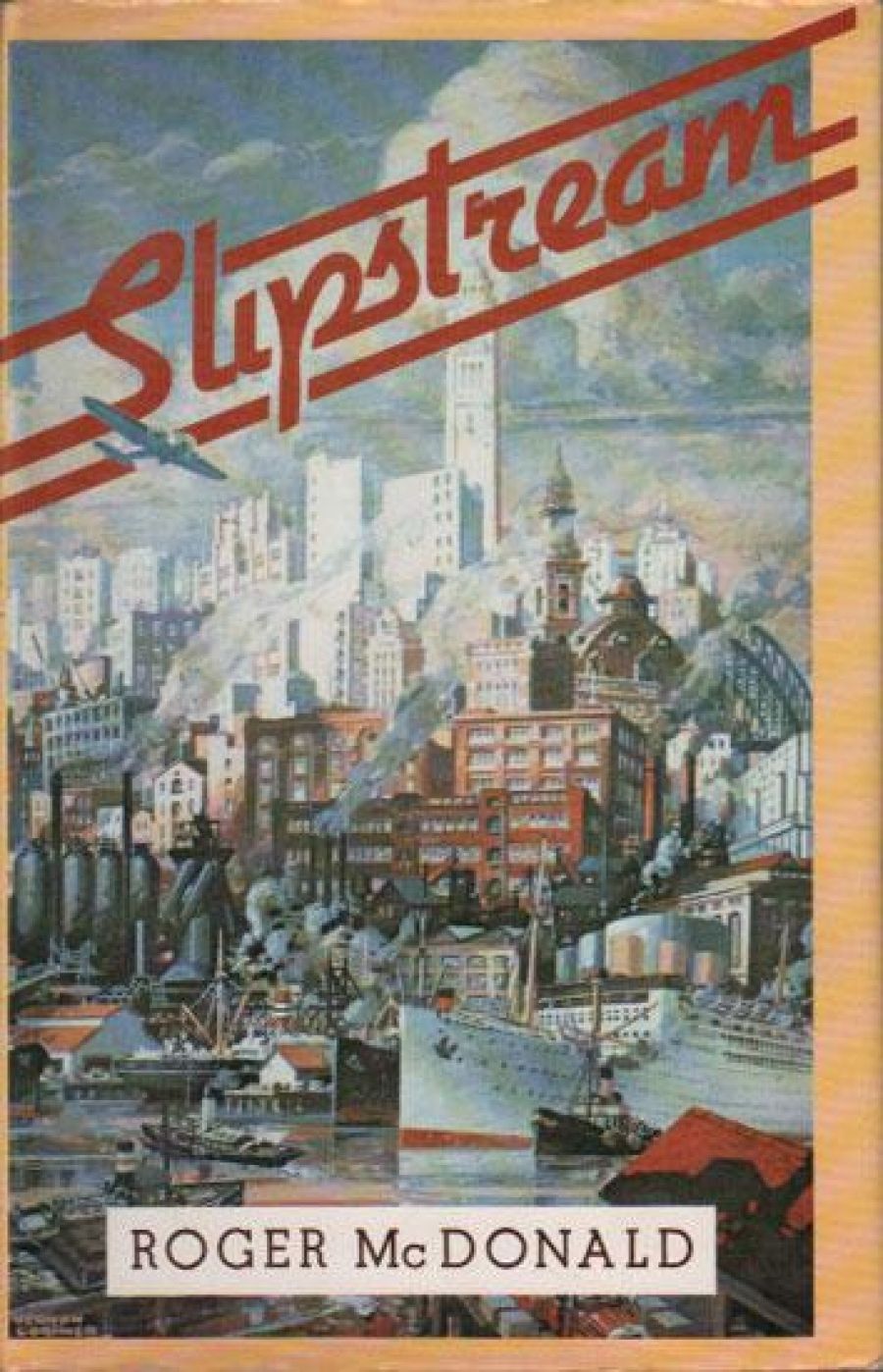

- Book 1 Title: Slipstream

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, 388 pp

We, like the peasants of pre-Homeric Olympus, might if fate willed see a god in the flesh, though Smithy, minus goggles and jacket, looked very much like anyone else at the tram stop. At Pittwater, fishing from a rowing boat with Dad, we were hailed by P.G. Taylor whom Dad knew at a mysterious haunt called The Club. He was pulling a dinghy out to the sea-plane he kept moored nearby. No Arcadian maiden I, but nevertheless my lumpy, sunburned, and very nervous self was abruptly hoist from rowing boat to dinghy and then jostled up a perilously swinging ladder and into the cockpit of the plane where I was instructed to sit at the controls and wiggle the joystick and never to forget the adventure. As if I could.

Some fifteen years later it occurred to me that, now I was earning $880 a year no less, I might fly to Brisbane for a holiday with friends rather than take the train. I’ve never forgotten the wonder of that first flight in a DC3 either and wrote one of the best poems in my first book about it.

So it may seem strange that no Australian of my generation wrote a memorable novel about those magnificent people in flying machines except, so far as I know, for Barbara Jefferis’s excellent and exciting Solo for Several Players, which is not really the kind of work I have in mind though it should certainly be back in print.

The delay is not strange at all if one takes into account the perspectives of time that are necessary as a rule before community myths enter highly imagined literature. This process once took centuries but accelerated in historic times although about fifty years still seems to be needed.

First we, the folk, select our heroes, sing songs and tell stories about them in their lifetimes and avidly read their biographies whether in books or newspapers. If the folklore is sufficiently compelling it lasts for generations until a Douglas Stewart is inspired by Ned Kelly or a Marcus Clarke by stories that are already myth to his creative mind. Slipstream appears just about when and as one might expect (and any day now Phar Lap, Les Darcy, and the Pyjama Girl may appear in first-rate fiction or drama).

For Slipstream Roger McDonald has invented a pioneer aviator called Roy Hilman who is a fiction although his career contains elements of well-known feats and events. This is not a novel for guessing games. By this device McDonald can embrace other myths of the 1920s and 1930s World War I pilots and dog-fighting; early Hollywood; the crazy graziers of the Australian high plains; the New Woman and, for good measure, a small serve of 1930s fascist secret armies in Sydney.

Earth and air, both in actuality and through representative characters, are frequently opposed, dangerous oceans must be crossed, fire is a constant risk and preoccupation though what consumes Roy Hilman is never-satisfied ambition and his mystique of perpetual youth they shall not grow old ...

Hilman is in many ways a simple character but a complex hero. Was he a great man ‘who bored a hole through the air for the first time’ as he, and many men who admired him believed, or ‘a three-ply hero typical of our times’ as Leonard Baxter, who probably analyses him more exactly than anyone else, thinks? Was he daring, far sighted but exceedingly careful and reliable or cold and, at least once, callous almost beyond belief? Was it fair to believe that ‘there was nothing inside him’ and that he was ‘once a brave youth but had never arrived properly at manhood?’

Readers must make up their own minds about Hilman but their task is perhaps more difficult than it need have been if the novel had run to greater length. Some of its ideas and events are over-compressed; some of its important characters are insufficiently explained; some of its questions are too abruptly posed, and this leads to fuzziness at the book’s very heart. To justify these harsh statements I give two examples. First is Hilman’s wife Olga.

Olga was a puzzle not only to me but to Claude McKechnie, a youthful reporter whose journalistic reputation soared with Hilman’s exploits. When, in 1957, two decades after Hilman’s death, McKechnie published The Roy Hilman Story he omitted almost all reference to the women in the aviator’s life. Overriding the reasons given for this curious decision in the novel I suspect that McKechnie, no more than I, knew what to make of Olga Hilman. There is a brief throwaway mention of her Russian-Jewish background but essentially, like Venus emerging on her seashell, beautiful Olga simply is.

The people among whom she exists are not Olympian in the least. Charles Coulter, an American millionaire whose money keeps Hilman aloft is perfectly human though his wife is another unexplained enigma, and perfectly human are Roy’s partner, horrible Harold Pembroke, and Leonard Baxter, pastoralist and politician. Venus/Olga deserts Coulter’s bed for Hilman’s wedding ring and eventually shuttles or scuttles back to Coulter again. The baby she bears to Roy Hilman dies; her crazy escape plan to an Australian alpine sheep station proves unworkable. Her parents are dead but had she no friends anywhere? No money of her own? No independence or pride? No possibility of working to support herself? No real choices? If not, why not? Her lazy sensuality is several times mentioned but in fact she is usually quite actively doing this and that. About the most understandable, if least forgivable, thing that Hilman even did was to smack her face much too hard and very bitterly.

My second example of over-compression is when, c.1934, Hilman is preparing his Hummingbird, a last word in plywood and doped fabric aeroplanes, for what will be his final fatal flight. A small, all metal plane lands near Hummingbird’s Mascot hangar and rates no more than a brief mention but it represents, I’m sure, a future that will hold no place for pioneer aviators. It is a precursor of huge, pressurised, stable aircraft. An attentive reader who notices the prophetic little machine may well ponder a better reason for Roy’s suicide, if his last flight was suicidal, than any character in the book realises. Roy Hilman would understand its implications. I am sure this incident is important because McDonald is that kind of craftsman.

Slipstream, however, is not shorter than standard novels, and I do want to emphasise its readability, pace, and gallery of interesting characters. Two mad women and one crazed man have parts to play which stress the opposition, in fictional terms, of Leonard Baxter and Hilman. Baxter, himself an adventurous man, is earth and rock with a salty tum of phrase as when he remarks of a monstrously villainous villain, ‘he should be boiled down and used on various weeds’. Baxter is also one of the characters whose tough honesty contrasts with devious Harold Pembroke. Baxter’s mad, abandoned wife who understood him very well says ‘In a counter revolution ... Leonard would be the one they called in from the provinces, the passer of sentences’. One of his roles is to balance Roy’s sister, a literally drunken Sybil. She and Leonard are the antiphonal chorus.

I have, until now, avoided reference to McDonald’s fine poetry because in one sense he keeps his poetry for itself he does not write or attempt that absurd contradiction in terms, ‘poetic prose’; but fine poets have fine ears and whatever faults are to be found in Slipstream they are not in its language which is splendid for its period. The journalism, and journalese of the time is fairly easily reproduced consider this caption for a newspaper photograph:

As Roy Hilman prepares for his record-breaking flight to the West he takes a well-earned tea break with his closest family (from left to right) Mrs Roy Hilman, Mr Ted Hilman M.M., and Mrs William Hoskins (nee Sybil Hilman). In the background is the mechanic T.C. Tandy, adjusting a propeller fitting. Absent from the photograph is Harold Pembroke who will serve as co-pilot.

That is perfect, but can be got from a library. Dialogue and tone of narration are far more difficult to reproduce. Certainly there are plenty of people still alive from Slipstream’s period but their ways of speech have altered down the years behind the novel I kept hearing voices, not as they sound now but as, though I had forgotten, they spoke when I was a child.

I have avoided the plot, which is strong, and the ironies that it leads to which are, in the concluding sections, handled with moving assurance. As a final comment Slipstream’s jacket which miraculously fits this well produced book deserves praise. It is reproduced from a water colour and gouache by Vernon Lorrimer or Lorimer, an English artist who worked in Sydney from the 1920s and painted his extraordinary Futuristic Vision of Sydney somewhere between 1928 and 1932.

Comments powered by CComment