- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letter collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The letters which form the body of this book are well edited and displayed, the biographical notes, although from necessity they are usually brief, are valuable – in these ways Decie Denholm has been a keen and careful editor. More about the letters later.

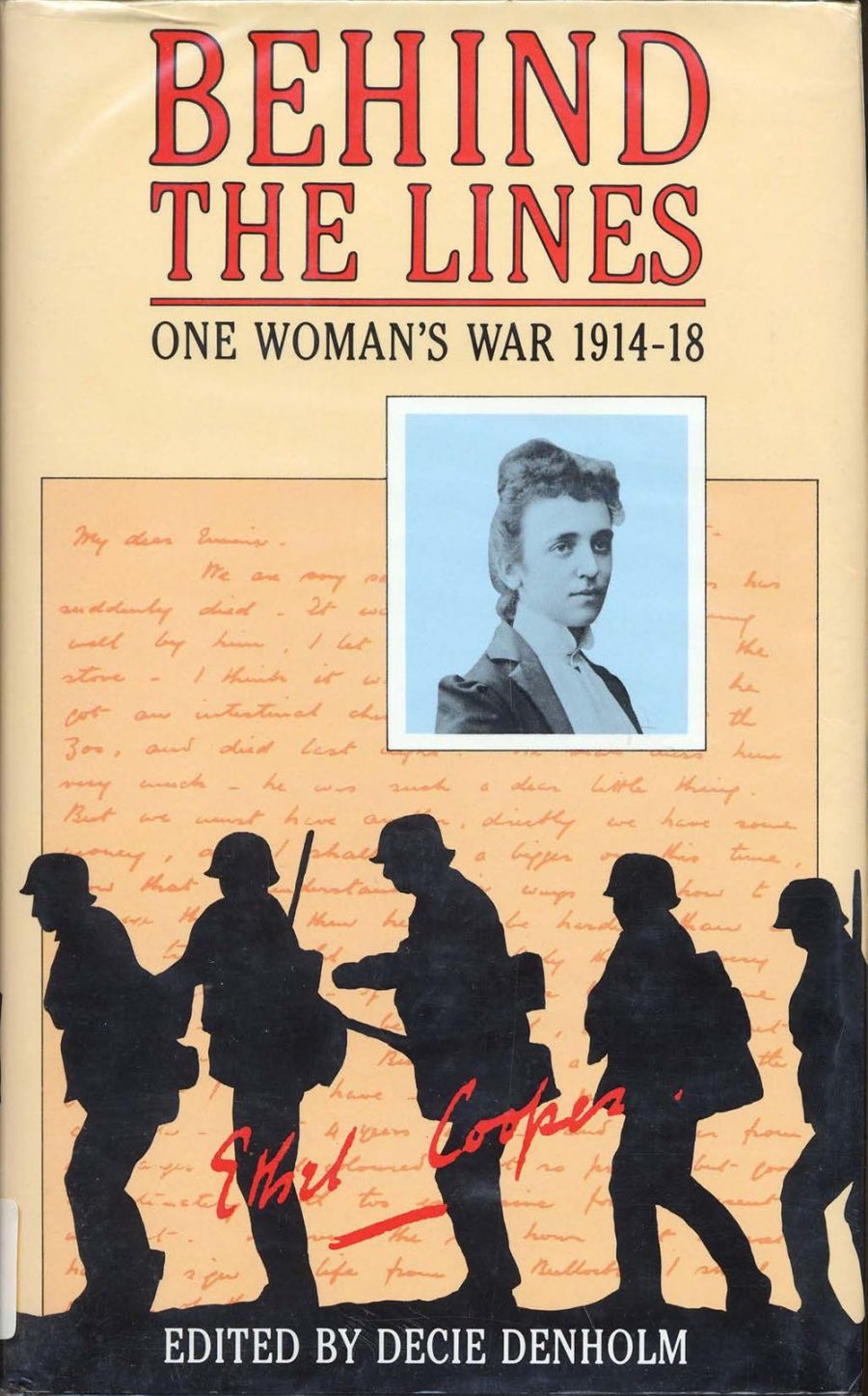

- Book 1 Title: Behind the Lines

- Book 1 Subtitle: One woman's war 1914–18: The Letters of Caroline Ethel Cooper

- Book 1 Biblio: Collins, 311 pp, $19.95 hb

In every age and era there are women, men and children who usually conform to whatever customs and traditions prevail. If this were not so Barry Humphries could never have succeeded with Edna Everage. But there are other people who do not conform or conform only in part. I’m not thinking of major eccentrics but, rather, of a woman I knew in my youth who was born c. 1850, and whose ideas of sexual morality would have made the Festival of Light look small ‘l’ liberal; but she smoked like a chimney, drank like a fish and cheated at cards.

As Virginia Woolf made plain, money makes it easier for women, and in fact for anyone, to live as they wish and please. Jane Austen made this plain too – there are more reasons than innate personality for Emma being forceful and Fanny Price docile.

This is by way of preamble to saying I find the introduction to Ethel Cooper’s 1914–18 letters inadequate, and irritating. If it is true, and it may be, that the Cooper’s sister and friends had unusually good educations and unusual freedoms of other kinds for girls born in South Australia in the l870s, at least six sets of parents (a grandmother in the Cooper girls’ case) can’t be seen precisely in the ‘mould’ of Victorian’ parents. And that being so this tally is only for one city with a fairly small middle-class population at the time, furthermore it takes no reckoning of certain other Adelaide families of the day who, in published accounts, seem not to have been exactly ‘Victorian’ in the stereotypic sense.

Yet, Ethel Cooper (1871–1961), whose letters from inside Germany throughout World War I are the real substance of this volume, was undoubtedly independent to an unusual degree for her times. Why? How? Chiefly, I surmise, because she had some regular source of income. In view of her four years’ preoccupation with getting funds through to ‘behind the lines’ I, for one, would be interested to know background details of her financial affairs and arrangements. Decie Denholm is silent on this central matter.

As well as being able to act, travel and live in an independent way, Ethel Cooper had a good and independent mind and considerable musical talent. She was small, nice looking but not beautiful and very energetic. She chain-smoked, drove very badly in later life, toasted sandwiches messily when, during World War II, some of her colleagues (she was an official censor) disliked her. Others were more perceptive. I’m not surprised because she sounds very similar to a peppery pioneer social worker who was once my boss and whom I came to admire, and even in a way to love, to the puzzlement of most of my friends and many of my family.

I can’t see that Ethel Cooper was particularly eccentric when young although by stuffy Australian standards she was unconventional. Rather, she was kind, passionately active on behalf of what she perceived as right, and brave. She had gone to Germany to study and teach music first in 1897, had returned to Adelaide between 1906 and 1911 and then she returned to Europe. She kept her friends both in Europe and Australia (including her sister Emmie) for long decades on end and over long separations.

Ethel Cooper was living in Leipzig when World War I broke out. Although it was very difficult to send mail from Germany, she decided to write weekly to her sister Emmie in Adelaide as she had always done. The letters add up to a kind of diary but, since letters are usually at least a little more distant than diaries from their composers, perhaps they were safer. All the same she kept them hidden against police visits, and, as the text discloses, sometimes destroyed sensitive passages.

At first Ethel truly wished to see the war through in Germany. About 1917, when she was heartily sick of being cold, unable to be with her loved ones during the griefs of war and tired of an insufficiency of wartime food (at least once she stole food from farmlands), it was impossible to leave though she then tried hard.

During those four years she had many friends and perhaps, very much perhaps, a lover. She befriended an English girl who bore a baby to a German and then, not without some problems, married him. Subsequently the girl acquired such useful lovers as a butcher who occasionally alleviated the food shortage for his lady love and Ethel.

There were concerts, lectures, and theatres too. All in all, Ethel’s four war years might have been a great deal worse and a lot more boring.

Decie Denholm speculates as to whether Ethel attempted a bit of spying. I doubt she did, though certainly when, in fortuitous ways, she became aware of the impending horrors of gas warfare, she patriotically, resourcefully and at some risk tried to get her news to England. (If you wish to follow ‘gas warfare’ through the index add page 140 which is not indexed but gives the triumphant end of the story.)

Ethel Cooper is no Rachel Henning, but her letters are literate, often amusing, affectionate, moving and, be it stressed, truly brave. Several good photographs add to the interest, and some of her news will interest historians of music.

Eventually, inevitably, and soon I hope, some historian either here, or in Britain, America or wherever will query and lay to rest the stupid ‘Victorian mould’ myth. One useful gun in that historian’s armoury should be Behind the Lines. Meanwhile for all readers it is an uncommonly rewarding book.

Comments powered by CComment