- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Custom Article Title: Reminiscences of a Friend

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A few Australian poems from J.J. Stable’s Anthology, A Bond of Poetry (‘The Man from Snowy River’, ‘Clancy of the Overflow’, ‘My Country’), Robbery Under Arms and For the Term of His Natural Life are, to my shame, practically all the Australian literature I can remember reading in my school days. My interest in Australian writers was stirred, really, by two events while an undergraduate at Sydney University. The first was two lectures given by H.M. Green, Fisher Librarian, on Christopher Brennan (an interest reinforced by the first performance at the State Conservatorium of Music in November 1940 of Five Songs – poems of Brennan set to music by Horace Keats). The second was a passing reference by Ian Maxwell in a splendid set of lectures in 1939 on three modem satirists (Butler, Shaw, Huxley) to Christina Stead’s House of All Nations. Maxwell was certainly up to date in his reading, as Christina Stead’s fiction was not at that time widely known in Australia and House of All Nations had been published only the year before. These two events made me realize that Australian writers were part of that great world of English literature which were studied at universities.

It was 1943 before I set eyes on an actual book by Christina, which happened to be House of All Nations, in (of all places!) Thursday Island, where I was stationed for a time in the Australian Army. In the Headquarters centre near our camp, I found an Army Education library surprisingly rich in nineteenth and twentieth century fiction and for a few weeks I went on a reading binge of Scott, Dickens, Thackeray and D.K. Broster! I then found a copy of House of All Nations. I was now in training for long novels and started it eagerly, only to be moved on from Thursday Island after reading a few pages. Even so the first strong impressions stayed with me for about two decades, until I was able to read Christina’s work properly. Over that intervening period, I remembered the list of quotations (from characters in the story) which constitutes the Credo preface, and Henri Leon and his blonde prostitute, and Marianne Raccamond, who figure in the book’s first scene.

When in the late 1950s I read The Man Who Loved Children and For Love Alone (in copies borrowed from friends) the characters Sam and Henny, Andrew and Teresa Hawkins and Jonathan Crow stood out for me with the same immediacy and clarity of Leon and Marianne on the early fleeting acquaintance with House of All Nations and I began asking why such a gifted writer was completely out of print, and still relatively unknown (though admired by a few perceptive critics) in the country of her birth. A very different kind of book Joyce Cary’s The Horse’s Mouth was the other novel I read in the postwar years that made me wonder how influential critics and reviewers could overlook such powerful and original work. Wanting to write about her work, I started corresponding with Christina in the early 1960s, seeking facts about the writing and publishing of her early books and asking her help in getting hold of volumes such as The Beauties and Furies, A Little Tea, A Little Chat, and The People with the Dogs, of which there were, at that time, precious few copies, even in libraries, in Australia. Christina replied with characteristic courtesy, giving me all the information sought and making arrangements for me to borrow from her brother in Sydney copies of her rarer books. The relationship thus begun grew quickly into friendship when I met her for the first time early in 1966 on sabbatical leave in England. I now had a contract to write a full-length study of her work for Twayne’s (New York), who had recently begun a section on Australian writers as part of their World Authors Series. By this time I was well acquainted with Christina’s work, but I reread the nine volumes to date and found myself even more impressed by The Man Who Loved Children and For Love Alone, which had seemed to me on very first reading to be her best books.

My visits to Surbiton where Christina and her husband, William Blake, had been living for the past few years were delightful occasions. I would go conscientiously armed with a list of questions and topics for discussion only to be subverted by the hospitality. There was nothing to do but go with the tide of the conversation and forget about work and duty. And what conversation it was! Bill was a charmer and a brilliant talker, who loved to throw ideas around and who possessed an incredible memory for details. He seemed to know exactly where the Blakes’ rather roving life on the continent and in the United States had taken them, when they arrived and how long they stayed in each place. He was too, a mine of information in matters of economics and politics. When the time came to return to Australia, it was like leaving lifelong friends behind. I was not to see Bill again. He died in 1968.

In 1969 Christina, as a Visiting Fellow to the Australian National University, was back in her homeland for the first time in over forty years. We had corresponded regularly since my return to Sydney, and her long, chatty letters had kept her voice ringing in my ears. It was good to see her again in gatherings of friends and on the more formal occasions to which she was invited. Though this was a short visit, which did not allow much time for travel, she seemed pleased to be back, to rediscover her homeland and to observe the vast social changes that had taken place since she left it as a young woman in 1928. She decided to settle here and came back in 1974 soon after the publication in England of her brilliant short novel The Little Hotel. In this same year she won the Patrick White Novel Award. The year 1976 saw the publication of her most recent book Miss Herbert, in New York. Since her return to Australia she has contributed short stories and articles and essays of a personal kind to various literary journals and newspapers.

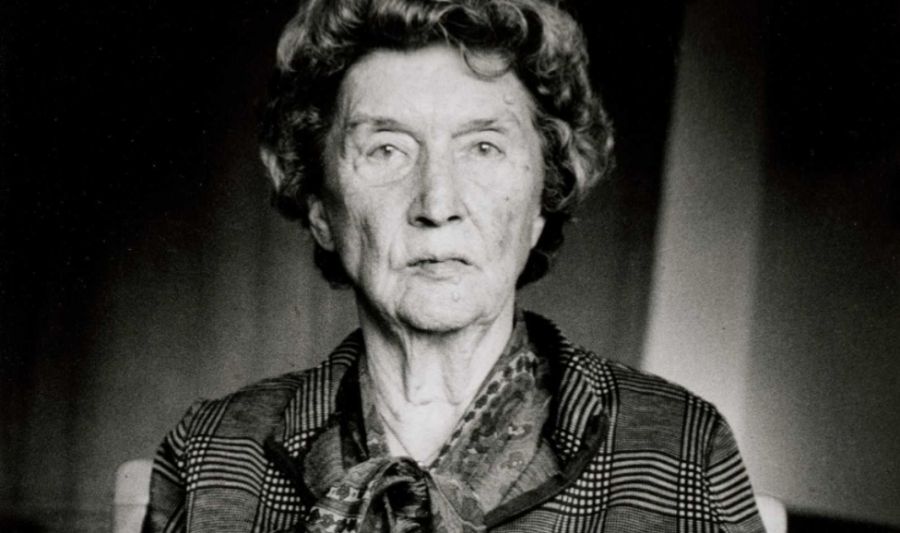

These reminiscences are those of a friend and admirer on the occasion of Christina’s eightieth birthday. I should like to think that my personal salutation carries with it the good wishes and gratitude of all who appreciate Australian literature.

Comments powered by CComment