- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Those who have hopes or fears of a Reagan–Thatcher hardline conservatism arising in Australia can forget it, if this newest attempt by the local ‘right’ to define itself is any guide. For a major topic, it is a listless, sickly growth from Australia’s whiggish soil that struggles – mostly unsuccessfully – for anything new to say.

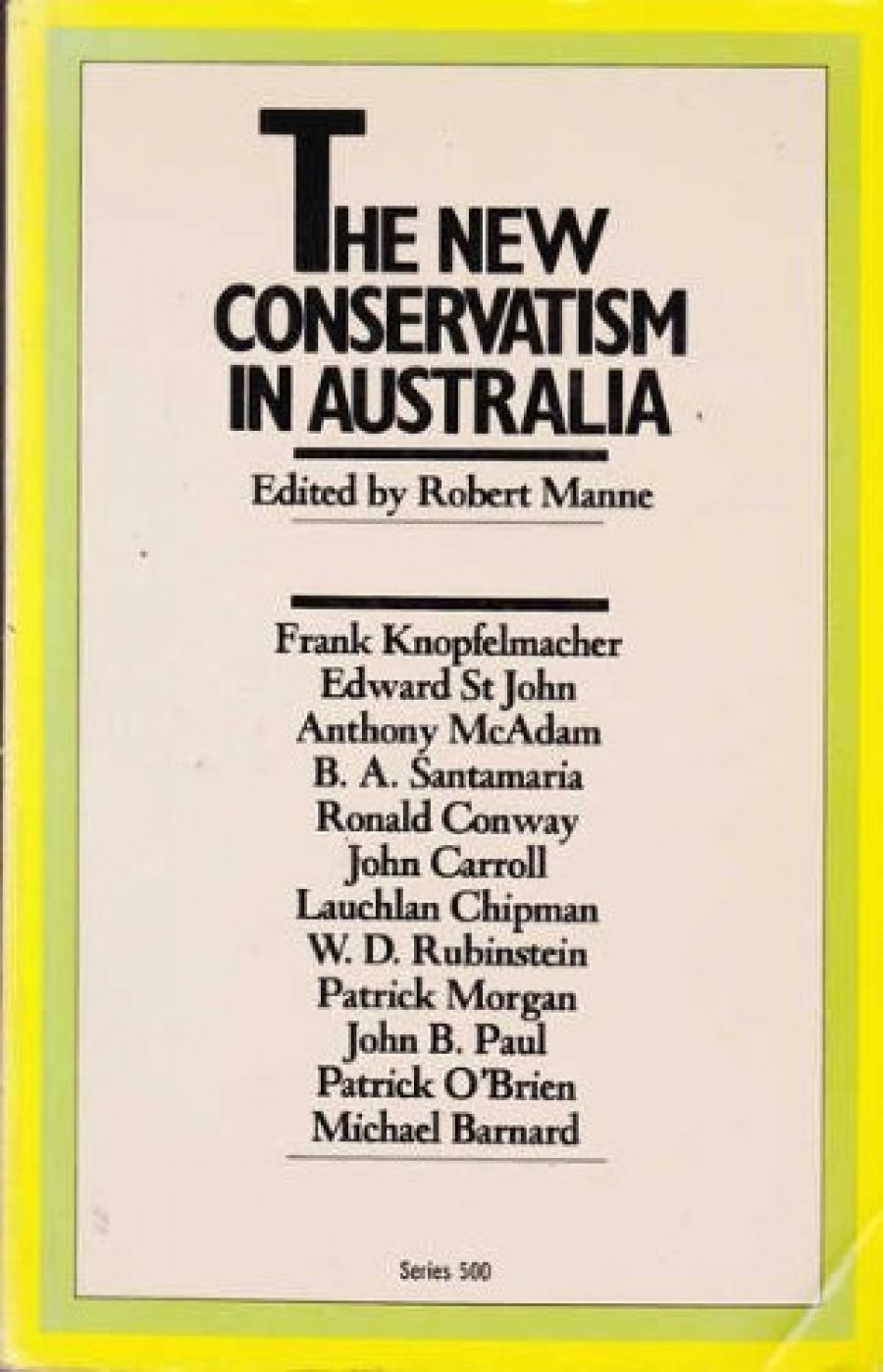

- Book 1 Title: The New Conservatism in Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: OUP, 290 pp, $25 hb

Indeed, the editor himself confesses in his foreword: ‘At one time I was tempted to include a section on the tension between Keynesian and libertarian economics, but quickly lost heart. I must admit to having no competence in economics whatsoever and little sympathy for some of the social consequences apparently acceptable to the more doctrinaire enthusiasts of monetarism and the un-shackled free market ...’

No one attempts to argue conservative approaches to, to name a few current issues, the constitution, law reform, the environment, Aboriginal affairs, feminism and the family, South Africa, trade unions and industrial relations or free trade and protection.

So we get back to the time-tried, not to say worn, favourites of the Australian intelligentsia: university and educational politics, mateship. the media, the Labor Party, Marx, Petrov, the Whitlam sacking, élites, the Cold War, etc. There is little that could not have been said at any time in the past ten years and much that has already been said. Even within the chosen ground of argument there is one most pointed omission, Vietnam: surely central to the issue.

Why ‘new conservatism’? The editor explains that most of the contributors ‘live in a complex and somewhat ambivalent relationship to the old and untroubled conservatism of the Menzies era and in particular to its Anglophile essence’.

Apart from the superficial and indulgent suggestion that Anglophilia was the ‘essence’ of the Menzies years – heyday of the tight American alliance and postwar Keynesian boom – it is now seventeen years since Robert Menzies retired.

This gaucherie suggests one of the many problems of the book: despite the name, it bears hardly any relationship to the Liberal Party or the governing of Australia.

The connecting theme, as far as there is one, is the enemy: the middle-class, Marxist, tertiary-educated left and its impact on education, journalism, broadcasting, and the public service. But it is an enemy whose cohesion and strength are presumed rather than demonstrated and who never comes into focus sufficiently for a reader to assess him – or the contributors’ understanding of him. I get the impression, however, that the enemy is viewed in highly stereotyped terms as a debauched, drug-taking new leftie fraud, instead of a multi-faceted phenomenon affecting most of the population to varying degrees.

As for the individual essays, the book gets off to a bad start by putting the silliest up front. La Trobe University sociologist John Carroll’s ‘Paranoid and Remissive: The Treason of the Upper Class’ is meandering, conspiratorial, and jargon-ridden. Like a lot of sociologists, he obscures further by an attempt to scientifically define the elusive and barely definable.

The Carroll contribution – and thus the book – begins b) discussing without explaining the campaign rhetoric of the 1980 Commonwealth election; I, for one, found it hard to remember two years later what distinguished that election other than that the Liberals, Then there is a defence of Malcolm Fraser’s left-baited prime ministership, which switches, half-developed, to an analysis of ‘remissive’ (which I presume means ‘trendy’ and is equally inexact) culture and ends up with a diatribe against the food and wine pages of the Australian. The author seems to see the new left rather than advertising revenue as the reason for such pages in the daily press.

If he is saying that the easy, undisciplined life has gone too far, he may be right, but most people are saying it today anyway.

‘The Children of Cynicism’, by Lauchlan Chipman, a Wollongong University philosopher, is the conventional criticism of ‘trendy’ education. I found nothing new in it, certainly no more than token suggestions for combating changes now many years entrenched. There is also an irritating flavour of the lecture theatre; surely there could be a bit more classroom experience, more smell of chalk in such discussions.

Frank Knopfelmacher can be an amusing and perceptive, if eccentric commentator, but he writes like an earnest sociologist and is uncharacteristically dull in ‘The Case Against Multi-Culturalism’. As noone is sure what multiculturalism means, the case against it is hard to mount. The argument that Australia should avoid splintering into ethnic communities and that the present rate of progress towards migrant absorption should not be artificially interfered with should have much support, but it does not need twenty-four pages of jargon and tables to make.

W.D. Rubinstein (Social Sciences Deakin University) demonstrates how small the larger Australian capitalist fortunes have been in the past, compared to those of Britain and the US. This weakens Marxist analyses of Australian society, for those who care to follow the ins and outs of this little argument which has raged so long and obscurely on the far left.

Patrick Morgan (English, Gippsland Institute of Advanced Education) struggles to fill eighteen pages with establishing a home ownership tradition to pit against the left’s mateship. It reads like notes for a good although not every exciting idea, rather than the completed article.

Those who have persevered so far may baulk at the next three essays: J.B. Paul (politics, University of NSW) demolishing yet again ‘Labour’s Petrov Legend’; Patrick O’Brien’s (Politics, University of WA) ‘Alternative History’ of the Whitlam years; and Sydney QC and former Liberal MP Edward St. John’s defence of the Kerr dismissal. Anybody who cares to retread these heavily trodden paths will find biased but fairly unexceptional summaries. O’Brien and St. John though, left me with the uneasy feeling that they believe a government going through a bad patch in mid-term should be consigned to the electors as a matter of principle.

The editor, Robert Manne, also gives a fairly unexceptional summary in ‘The Rise and Fall of the Communist Movement’.

B.A. Santamaria’s latest overview of ‘Australia’s Strategic Environment’ interestingly analyses the implications for this country of cold-war power plays over Middle Eastern oil. Though developing a familiar topic, it is the best of the bunch and shows more signs than most of thinking ahead. But over nearly half a century and countless millions of words of punditing, the grand old man of anti-communism has built up, as well as experience, a lot of lead in the credibility saddle.

The ‘Soviet Danger’ by Michael Barnard is a collection of six columns by the Age’s house conservative, published during 1980 and 1981, in which he trenchantly warns about the Czar over Poland and Afghanistan. He makes a good case against the Russians, but I have yet to hear anybody say the opposite.

Anthony McAdam, another controversial columnist, demolishes the Marxist analysis of imperialism as a fashionable catch-all approach, though he admits it has sometimes been right. He then abruptly switches, towards the end of ‘Imperialism and the Third World’, to an attack on the Brandt Commission’s proposals for redistribution of the world’s wealth from ‘north to south’ and criticizes Malcolm Fraser for supporting it. Perhaps there is a connection between the Brandt Commission and Marx and perhaps Mr Fraser is really going to do something, but I must admit I did not readily grasp the connection between all three.

Ronald Conway concludes the book by arguing for a Tory-Conservative approach to life, as opposed to his pet hate, Australia’s dominating Whig-Liberal tradition, on ‘The Level Vision: The Religious and Ethical Basis of Conservatism’. It’s interesting, but I couldn’t think of one current public issue or problem to which this theory could be usefully applied. One must also note how beguiling a case can be built up for almost anything by seeking out long historical traditions and then presenting them in a few pages.

To summarise, the significant thing about the essays is how dull they are: too far from the mainstream of Australian issues, too restrained by the campus view, too jargon-ridden and ‘academic’ in style, too backward-looking, too preoccupied with countering the enemy; and really with too little to say.

The overall impression is that the book has been put together for students to prepare them against the campus heresies of the left and it would certainly help to be 19 and not have heard it all before.

But I suspect that, here, the Banquo’s ghost of Vietnam may be waiting to haunt the editor and his contributors over its omission. Even nineteen-year-olds may suspect that the famous credibility gap originating in Vietnam is still with us.

Comments powered by CComment