- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Yoogum Yoogum is the second collection of verse by a young Queensland Aboriginal whose earlier volume, Kargun, did not get a great deal of attention when it was published in 1980. Fogarty’s themes are ones increasingly heard in contemporary Australian writing: the historical dispossession of the Aboriginals, the present decay and demoralisation of Aboriginal society, white greed and exploitation, the primacy and potential of the land as a key to fulfilled life, the plight of (Aboriginal) women, the pathetic dispossession of Aboriginal children, solidarity in the cause of redressing the wrongs to Aboriginals, the fundamentally positive values of Aboriginal society, the possibilities for solidarity with other groups in the struggle for social justice.

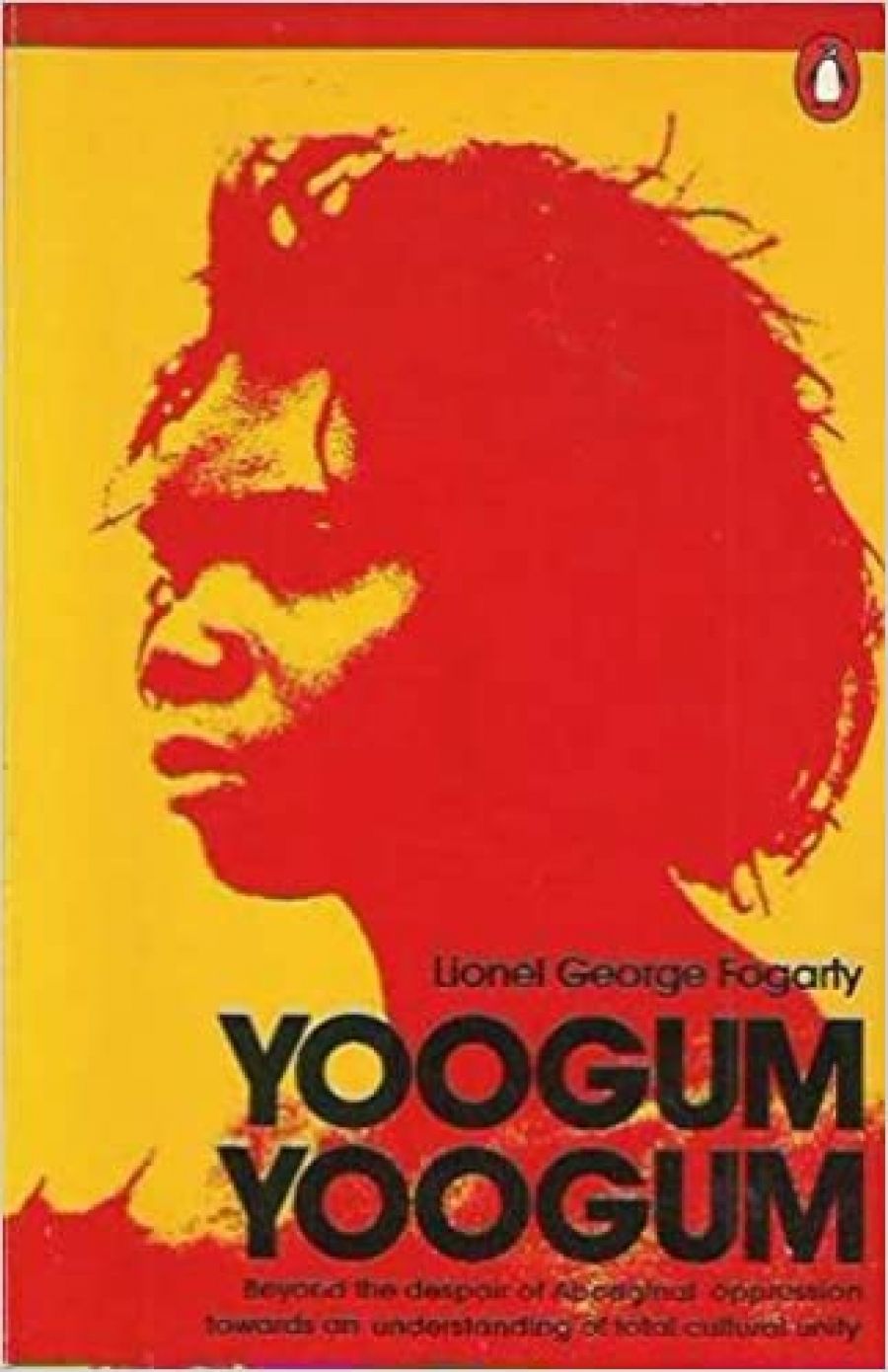

- Book 1 Title: Yoogum Yoogum

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, 132 pp, $4.95 pb

Fogarty is only the third Aboriginal writer to have produced two volumes of verse, so it is instructive to see where he moves away from his predecessors, Kath Walker and Jack Davis. His first volume was in the tradition of their verse, although angrier and more contemptuous of the perceived oppressors of the modern Aboriginal. Yoogum Yoogum moves inward to a private fragmented world in which the forcefulness of the emotions is held in tension with a surprising fondness for wordplay and a sense of the self-conscious opacity of language.

Yes, childhood measles killed away forty frontiers violently.

We declined they argued to prolonged exposure.

Getting tumbled relieves the pressures of

assimilation.

Renegade hostility conspires theory used by pale faced behaviourists.

Resistance rejected

rules stealing a free canoe away for strays.‘Have’

One of the most telling strategies of the ethnic protest poet is a simple, direct statement of plight, whether angry or lamenting. This is what makes poems like Kath Walker’s ‘We are Going’ or the Fijian, Raymond Pillai’s, ‘The Labourer’s Lament’ so effective. Fogarty eschews such directness in this volume, but exploits occasionally a different kind of simplicity: a chime that has suggestions of a nursery rhyme.

So I wrote.

But will you remote, note Space took a pace

Rat race

whata play, ace‘Tired of Writing’

Such chimes draw upon phrases from advertising jingles and from pop songs, just as other poems parody the officialese of committees and working parties. They help to structure verse which in a search for Dylan Thomaslike density has eliminated articles and punctuation, and in doing so risks obscurity. It is impossible, I think, to unscramble the relationship between words in:

Silence merits

muttered black stones

shine touch divine ballad wing tipped water lilies.‘Sentiment Transcends’

The principal sources of such difficulties seem to be the speed with which the poems were written and the lack of reworking. In every sense they are occasional poems. All but a handful of them are meticulously dated, and some of them are also flagged with other memoranda relating to their genesis: ‘The night I spoke at Trades Hall’; ‘I write before our new baby’. The dates show most of the seventy-odd poems are very recent, four fifths of the volume being written between 12 May and 16 August 1982, and as many as four poems have the same date. These then are the unburdenings of the mind at white heat – a journal of ideas, images and world combinations, and they never entirely escape from the selfreflexive quality which that implies.

They are occasional in a different sense also. Fogarty’s earlier book had been published by a friend from within the Aboriginal community. With his second volume they approached commercial publishers and were fortunate to catch Penguin just as that publisher was examining its soul over what attitude it should take to Festival 82 and the various calls for a boycott. Publishing an Aboriginal writer seemed a much more positive action, however, so they rushed production through in something like two weeks and launched the book as part of the Aboriginal Land Rights campaign in Brisbane. Consequently, one should forgive the greater than usual number of typos.

The poems suggest nothing so much as a journal-notebook with the sections divided off by Amos Tutuola-like titles: ‘The Worker Who, the Human Who, the Abo Who’, ‘Many Old Came Initiated, Ours Came Abandoned’, ‘Mosquitoes My People are Sweetened Air’. At their best they fuse passion with a thoughtful complexity of diction. European education is encapsulated neatly:

We chew snake accurately

careless when they civilize us

we technically rub daffodils, roses

lakes recreating for fluttering instincts.Morning Grey, Valleys Ray’

Published English-language poetry by Aboriginals is not yet so common that new volumes can pass without notice, as every new volume is likely to extend the range and change the contours of this nascent tradition. Despite its occasional incoherence, Yoogum Yoogum extends the range significantly by the ambitiousness of its language. These are not poems which will immediately gain the popularity of some of Kath Walker’s, but they are poems that will make possible other poems, by Fogarty and by others, and these will be richer for the experiments in the present volume.

Comments powered by CComment