- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

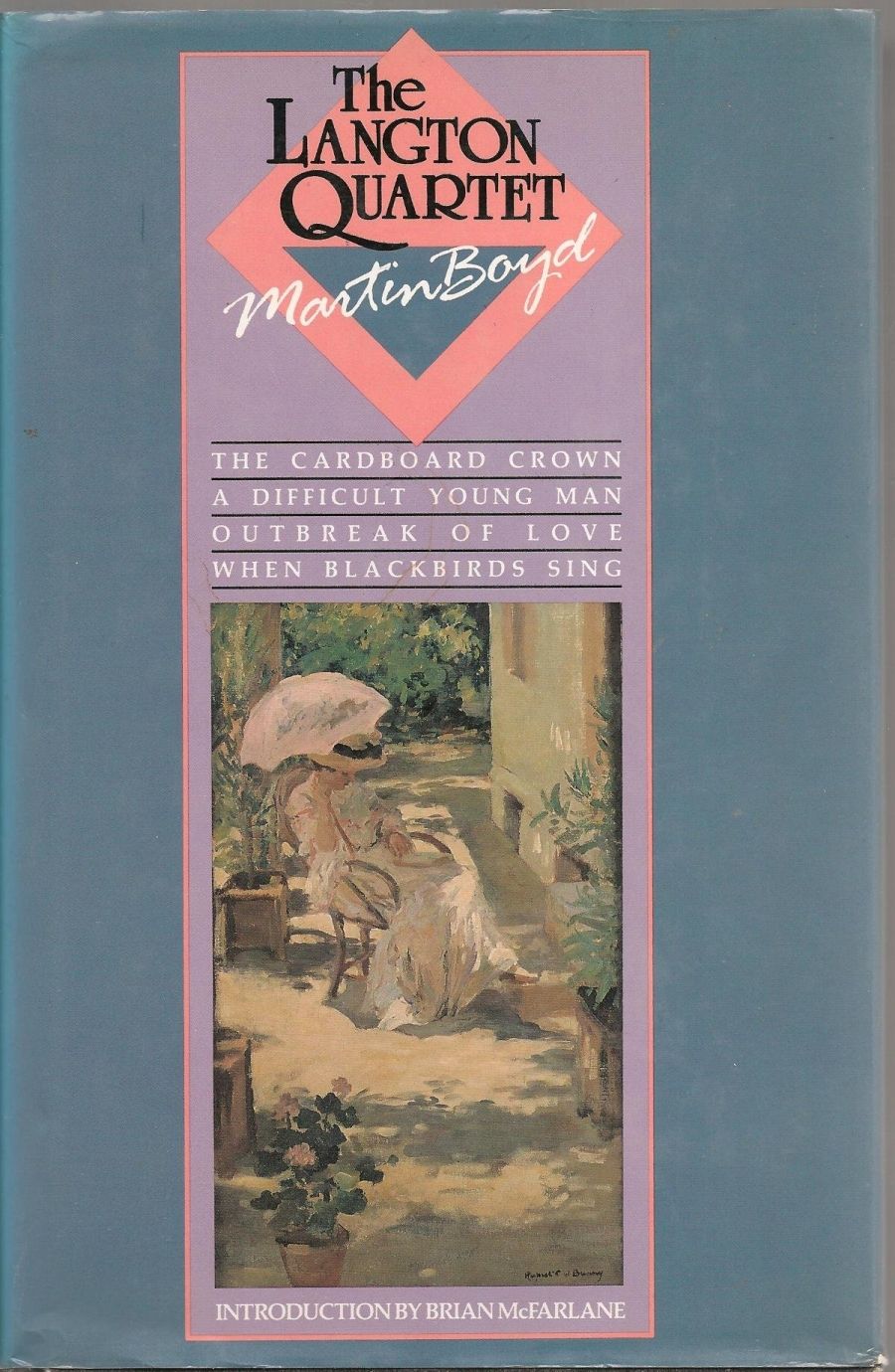

Brian McFarlane’s small book on Martin Boyd’s Langton novels is a particularly measured and useful study. He makes no grand claims for Boyd but sees and appreciates him for the writer that he is when he is at his best, and the Langton novels – The Cardboard Crown, A Difficult Young Man, Outbreak of Love, and When Blackbirds Sing – certainly see Boyd at his best.

- Book 1 Title: Martin Boyd’s Langton Novels

- Book 1 Biblio: (Studies in Australian Literature) Edward Arnold, 60 pp, $4.95 pb

The blurb on the back of this little volume states that this series ‘offers an incisive account of a major Australian work or body of poetry which is often studied in schools, colleges and universities. The chief emphasis is on structure and meaning, but such work is also posed in its appropriate historical and cultural context.’ This is, extraordinarily, just what Brian McFarlane does. The intellectual task of discovering ‘meaning’ in the Langton novels is possibly not spectacularly daunting, but McFarlane has a very impressive, and very sympathetic, grasp of Boyd’s special qualities. He is quite illuminating about those especially pleasurable aspects of Boyd’s work – his tact, his grace, his pithiness, his subtlety, and his remarkable ability to reverberate an entire chamber of understanding and feeling with an apparently slight phrase. He makes one recall, for instance, the artful conception of Cousin Hetty, that ‘moral thug’ who, when she telephones Arthur fifty years later has a voice that is ‘deep and kind and old’. Boyd also has compassion.

In his later rambling autobiography, Day of My Delight (1965), Boyd recalls being ‘very happy in that limited world’ of his parents, where life was ‘consistently witty in a rather “Punch” and Anglican style’. He never really escaped that limited world. McFarlane recognises and accepts this and although he can see some of the really bad things about Boyd’s work – the quite simplistic and shallow philosophies; the not infrequently haphazard structures – be himself has the grace and the tact to face these failings within the context of the vitality and charm of much of the best work. Boyd, after all, stands not as a novelist of any great intellectual distinction, but as a novelist of Manners. Manners – of what the manners and mores of a particular society reveal about particular people and vice versa. As McFarlane points out it is only in social interaction that human relationships function and it is only here that one finds meaning. It is too easy to slip the novel of Manners into the genre of Trivia. Life is primarily concerned with trivia, it functions through trivia, yet this doesn’t automatically make life worthless.

As McFarlane’s sympathetic treatment makes so clear Boyd’s central characters are not at all trivial. Their lives may appear to be, but they are not. Even a figure as banal and as irritating as Aunt Mildy has dignity and poignancy in her frustrated and wasted life. McFarlane’s perceptions about character in the novel are wise and always worthwhile, if not surprising.

So – this is a most valuable book to students of Boyd. It is encompassing, introductory without being too general and it maintains a generous detachment. Early on McFarlane notes Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s comment about the Langton novels being ‘distinctly private houses rather than public buildings’. It is obvious that McFarlane appreciates that some of our most pleasing and delicate pleasures take place in the intimate charm of the private house, not m the splendour of the public building.

Comments powered by CComment