- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Short Stories

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

This collection of twelve stories by the author of The Savage Crows and A Cry in the Jungle Bar seeks to explore and define what Drewe sees as a part of our national psyche, the preoccupation with the coast and with the ‘careless violent hedonism’, as one of the characters puts it, of beach life. In ‘Looking for Malibu’, David Lang, who appears in several of the stories, defines it for a then fellow expatriate in a discussion about criminals on the run. ‘If their enemies were middle-class Australians they’d know where to look for them,’ he says. ‘You know something? When Australians run away they always run to the coast. They can’t help it. An American vanishes, he could be living in New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, the mountains, the desert, anywhere. Not an Australian-he goes up the coast or down the coast and thinks he’s vanished without a trace.’

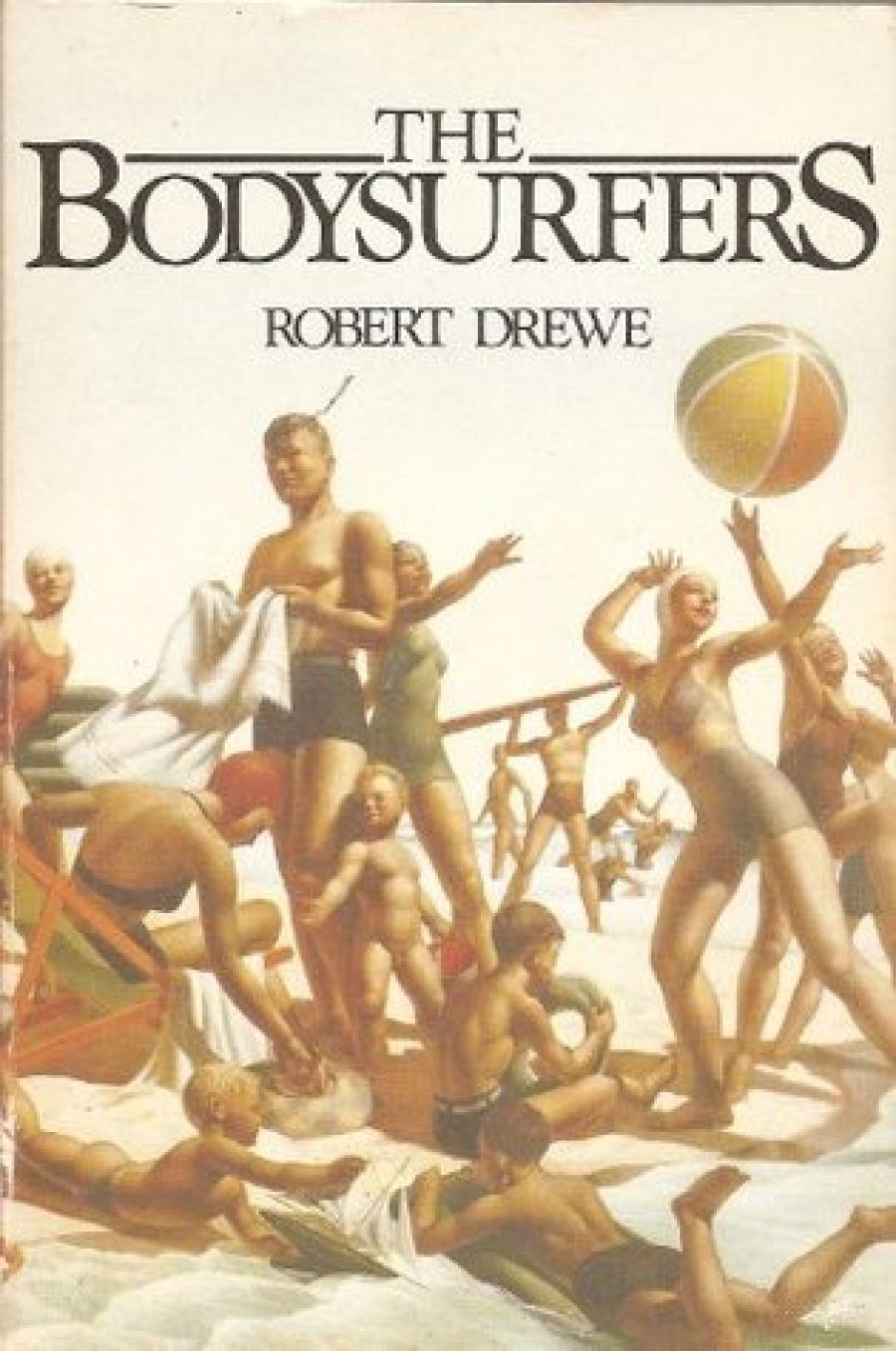

- Book 1 Title: The Bodysurfers

- Book 1 Biblio: James Fraser, 6.95 pb

All of the stories are set on the coast somewhere – Sydney, Western Australia, California – and all have something to do with it. The opening story and one of the best in the collection, ‘The Manageress and the Mirage’, is set in a hotel on the coast of Western Australia. The narrator, Max, and his brother David and sister Annie are having Christmas dinner with their father; their mother had died in July. The children become aware that there is an intrigue going on between their father and the hotel manageress. The story ends with the children’s disappointment and disillusion subtly evoked in impassively described details: ‘One after another, David, Annie and I snatched off our party hats, crumpled them and threw them on the ground.’ The last lines are these: ‘From the car you could see into the manageress’s office. She was combing his hair where his party hat had ruffled it. He came out whistling ‘Jingle Bells’ and the stench of his cigar filled the car.’

Another memorable story, ‘The Silver Medallist’, narrated by David Lang this time, hinges beautifully around the absurd incident of a swan which has drifted ashore and which the central character Parnell, a vain ex-Olympic swimmer, sets about returning to its natural habitat. At the second attempt he succeeds but he has made something of a fool of himself in the progress. Later that night, he returns to the surf club and burns it down. In ‘Stingray’, David has had a wretched day at Bondi and feels like getting drunk but instead decides to go for a swim. ‘The electric cleansing of the surf is astonishing, the cold effervescing over the head and trunk and limbs. And the internal results are a greater wonder. At once the spirits lift … The brain sharpens. The body is charged with agility and grubby lethargy swept away.’ As he thinks these thoughts, David is attacked by a stingray and comes close to losing his life.

Perhaps more than the motif of the coast, what links these stories is the sense of crisis and disconnectedness in the lives of the characters. Marriages are breaking up, affairs are unsatisfactory, parents worry about their children, successful professionals (the majority of Drewe’s characters) experience periods of crisis in which their lives suddenly become meaningless to them. In a manner that seems almost obligatory in collections of short stories now, Drewe links many of the stories by having certain figures recur. Perhaps consciously, his portrayal of the three generations of the Lang family seems to mirror some of the changes that have taken place in Australian life over the last quarter of a century). Confident business man gives way to subdued, maritally unfulfilled professional, who in turn gives way to aimless, would-be artist son, living off the dole and occasional cheque from his father.

This is a rather pessimistic collection. Drewe’s prose, low-key subdued, searches constantly for the telling detail as in ‘The Managere and the Mirage’, concerning the children who had recently lost their mother: ‘Annie’s plaits looked irregular; one was thicker than the other; Dad still hadn’t mastered them.’ The endings are most often inconclusive, enigmatic. On the rare occasions when Drewe tries to spell things out, as in ‘The Silver Medallist’, the conclusion looks falsely imposed. In a way, it could be argued that Drewe is confirming the national stereotype of Australians living out lives of quiet desperation papered over by material comfort and hedonism (it is no surprise to see a quotation from Manning Clark as one of the epigraphs to the book), but the stories are more original and humane than that: they are sharp-eyed and sardonic but rarely cynical. The exceptions are two passages referring to women, who in general are not as sharply differentiated in the stories as the male figures. This is Max, thinking about his new lover Anthea: ‘Women were so wonderfully dishonest and dismissive when it suited them. In the face of this treachery Max quite often felt more in league with the husband or boyfriend he was cuckolding than with the woman in question – equally, eternally ignorant of the extent of female fraudulence.’ Or his brother David eyeing his new wife, who is sunning herself, topless: ‘I wonder if women know what they’re doing ... How did those tits which had been used to sexually tempt him at 3.00 a.m. suddenly at 11.30 become as neutral as elbows? Who’s kidding who?’ Such lapses into shallowness, fortunately, are rare.

Comments powered by CComment