- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Racism at work

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The bias in settlement and exploitation of nineteenth-century Australia was essentially English. These Antipodes were classed as a wide white land, for the Anglo-Saxon. A Scot or a Welshman could have a place. They were Celts, and classed as ‘British’, close to the centre of England’s Empire, the greatest ever seen.

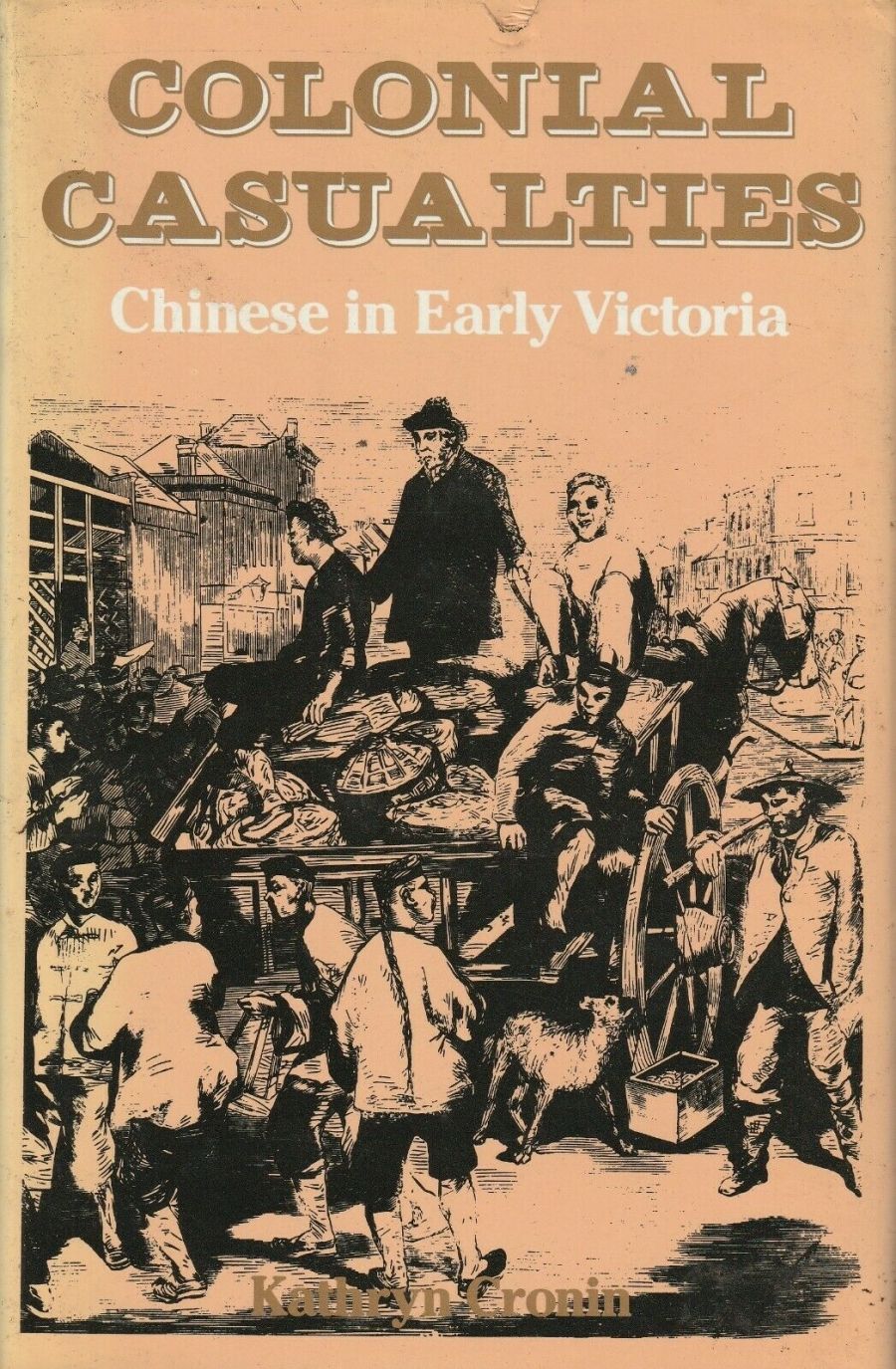

- Book 1 Title: Colonial Casualties, Chinese in Early Victoria

- Book 1 Biblio: MUP, $17.95, 175 pp

When gold was exploited in Victoria from the 1850s, and with the swift influx of many thousands from many countries, continental Europeans were often treated quite well – better, the scan suggests, than the Irish. Differences of trade, politics, and attendant brands of Christian religion were sorting out through wars and the marketplace. The grand new age of imperialism was shaping the English way. Differences might still be strong, yet linkages had to be maintained.

No so with aliens, those of exotic, largely unknown languages, customs, and beliefs; foreigners to the factory floor.

Colonial Casualties examines the experience of our most populous, alien, gold rush borne immigrants to Victoria: the Chinese. Kathryn Cronin tells of ignorance, culture clash, suppression, injustice, savagery; also of dashes of sympathy or cases of mercantile success. She quotes Sire Frederick Roger of the Colonial Office in 1861. Having read, ‘with very great and painful interest the accounts of the Colonists’ dealings with aborigines’, he opposed importation of Indian ‘coolies’ to Queensland, where they might be ‘exposed to casualties of this kind’. Even those from alien lands won for the Empire might not be safe. Kathryn Cronin readily transmits the observation to Victoria’s Chinese immigrants. Her message is that prejudice and assumed superiority will be aggravated by insecurity and fear; that the clearest target will be what is alien.

So, when Victoria’s gold yields fell and recession came in 1857, there were savage anti-Chinese riots on north-east Victoria’s Buckland field. Attitudes which bred legislative measures such as discriminatory taxes escalated to organised physical violence.

Exodus, through emigration or death, reduced the Chinese population. Historians, says Kathryn Cronin, tacitly suggest that persecution relaxed in the 1860s and 1870s; revived in the 1880s. She claims that it was just as strong in the intermediate decades. Her evidence is slender. A number, notably Geoffrey Serle and Graeme Davison, have worked Victoria’s 1850s or 1880s; but a gap persists for the 1860s and 1870s. A spanned base is lacking for Kathryn Cronin.

In addition, work on the Chinese has rested on diaries and letters of European diggers, on reports of government officers, and findings of government enquires; or the newspapers, of which some like the Bendigo Advertiser has a heavy anti-Chinese bias. Where, however, is quantitative work from records of courts, the police, or solicitors? Andrew Markus has suggested there is a lack of such work (see his ‘Chinese in Australian history’, Meanjin, March 1983). For example, records for Beechworth or Creswick. I am told by Morag Loh that samplings, fresh from previously unexploited material at the Melbourne University Archives, suggest that the Chinese while often preferring to remain an alien group (see Cronin’s ‘clans’), would contest a law, even against each other, and receive treatment, parallel to European cases.

Further, Cronin translates clanism to mean defence against unjust ‘mining bigotry’. However, the bigger the target, the more it will be aimed at. Irish Tipperary boys were persecuted. So too pairs or small parties of Germans or Italians; even Danes, as evidenced in the emasculatory editing of Gold! Gold!: Diary of Claus Cronn, by his Castlemaine descendent Cora McDougall. But these were small shifting targets.

Which leads to a notable, but scarcely explored element in this, the first book to draw together thematically, with integrity and indignation, the story of Victoria’s colonial Chinese immigrants. The ‘clan’ arrangement, whereby Chinese miners were financed by monied people back home and Chinese merchants here, assiduously ensured repayment of loans with interest, and a tithe of the first year’s yield of gold. This was a structure familiar to making a ‘British Empire’, to the power of money. The defection of 150 Melbourne Chinese merchants in 1859 from support for passive resistance by thousands of their countrymen in Bendigo and Castlemaine against discriminatory taxes is to the point. Kathryn Cronin observes that Geoffrey Serle is the only person to have noticed this resistance, equal at least she says to the rebellion at Eureka. But the merchants paid the tax, and the power base of the resisters on the goldfields was obliterated. This is not an alien scene.

At the end of her book Kathryn Cronin complains that old prejudices persist, in ‘an armoury of anti-Chinese images’. I don’t think so.

England recedes; new times are with us. Certainly Australia has been and can be racist. But the 1939–45 war introduced big changes. We were shown by Mr Winston Churchill, spokesman for a dying English Empire, that our English ‘Mother Country’ would dump us on any other doorstep; but would of course want recourse to later investment in our lands and mines. I remember Arthur Calwell (and he repeated it in his autobiography) speaking many years ago to Geoffrey Blainey’s students of Economic History on his experiences as post-war Minister for Immigration. Late in the war, he said, the government knew we would need migrants, that Britain could not fill the quotas. Whereas Hitler’s Ayran belief had been fought against, Calwell had to ensure that the first boatloads of continental European migrants were fair-haired and blue-eyed; not the ‘Jews’, ‘wops’, or ‘dagoes’ who arrived in the 1930s. The Anglo-Saxon myth was still with us. The new migrants, as I saw, growing up in Albury, were immediately ‘Bloody Balts!’ That changed. It was found they were useful at parties, to sing and play the piano; also, like ourselves, they faced a new world. They assimilated. More importantly so did we.

More recently Australia sees its place, economic and geographic, in Asia. And increasingly Asia supplies our migrants. We shape as a truly multicultural country; towards a distinct identity, but of a global image. Kathryn Cronin can take heart … unless the empires strike back, making casualties of us all. Look to the Falklands; not too far away. And what might the United States, USSR, Japan, or China do to us? Colonial Casualties, an angry book, provokes images beyond its content. That is a significant part of its value.

Comments powered by CComment