- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Norman conquests, Lindsay style

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

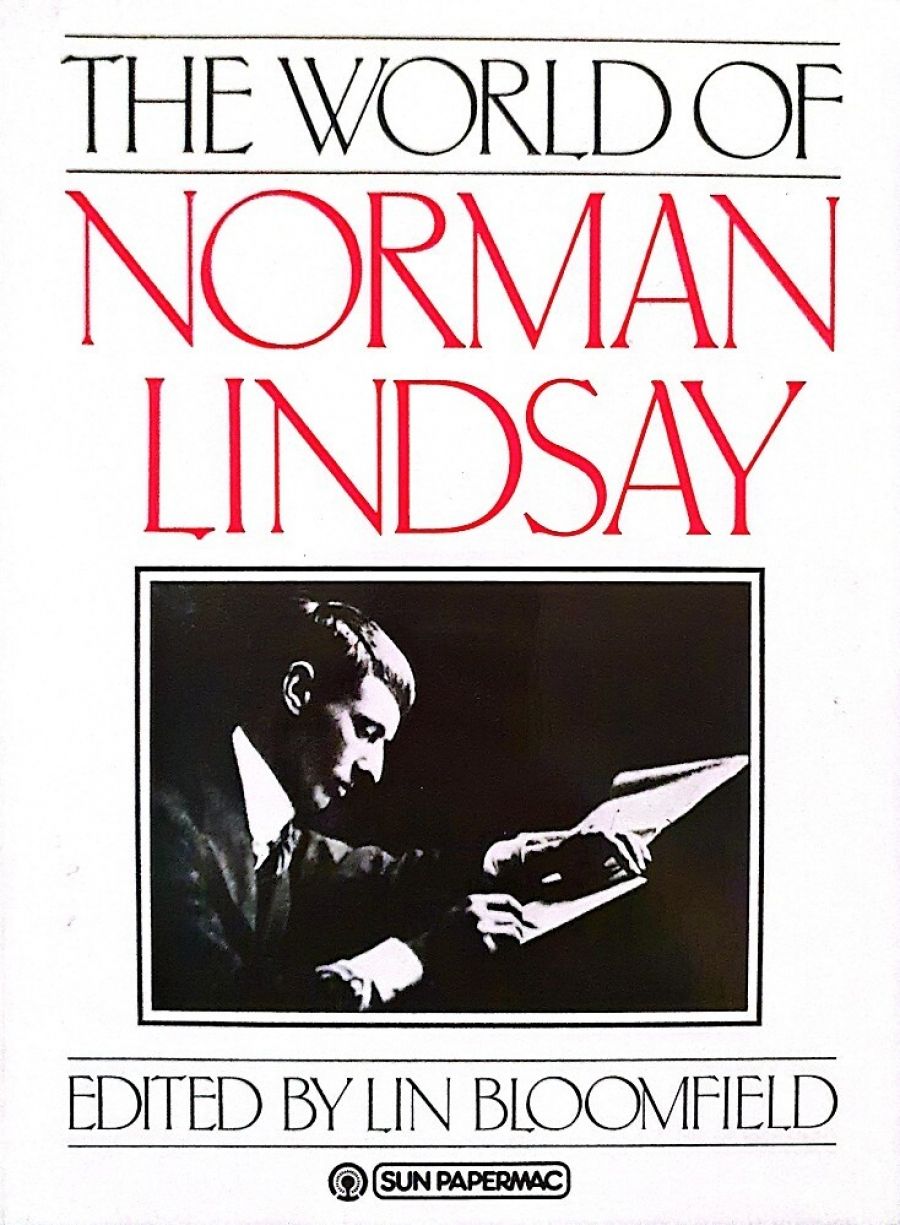

The World of Norman Lindsay is compiled by Lin Bloomfield, proprietor of the Bloomfield Galleries in Paddington, NSW, and an authority on Lindsay’s work. It was first published more expensively in 1979. This elegant paperback will make it widely accessible, which is a matter for satisfaction. It contains comprehensive, short, expert articles about Lindsay’s life and achievements as an artist and the reminiscences of Lindsay’s children, grandchildren, models, friends, and colleagues. Good illustrations, some in colour, cover every era of his works in all their variety, and the book also includes photographs of people and places.

- Book 1 Title: The World of Norman Lindsay

- Book 1 Biblio: Sun Papermac, $14.95 pb, 150 pp

- Book 2 Title: A Letter From Sydney

- Book 2 Biblio: The Jester Press, $27 pb, 58 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

As to Norman Lindsay, whether or not posterity gives him the accolade ‘genius’, he was undoubtedly a late flowering of the Renaissance universal man. Nearly a quarter of a century since he died at the age of ninety it is obvious that, having been a contentious legend for most of his lifetime, he is now an established myth figure likely to be as enduring as Ned Kelly and far more interesting.

Some cynics maintain that the continuing publication of books about Norman, his achievement and his ‘circle’ is a mere commercial exercise directed at avid collectors. This attitude begs two questions: firstly, Lindsay’s circle, throughout his long life, included, or touched upon, most of the talented artists and writers of his times as well as many of the country’s most influential people in other fields. No one now or in the future can assess either the arts or events of his period without coming up against Lindsay. It might be argued that several of his weekly Bulletin cartoons shaped events – certainly they helped, for better or worse, to shape Australian attitudes. Secondly, though there are undoubtedly many avid collectors of Lindsayiana their numbers cannot account for total print runs, or for the public popularity of his house at Springwood, now a National Trust museum, and Gallery – 20,000 visitors a year, says Douglas Stewart in his article about the Gallery.

Fashions and experts come and go. . . people continue to admire Lindsay’s paintings, etchings, drawings, sculptures, ship models, novels, and The Magic Pudding.

Good for people! Sydney people have continued to like the Queen Victoria Markets Building which is about to be restored at great cost with the blessing of the City Fathers and the National Trust. Had people listened to Ray Lindsay and his generation of opinion-makers, the old building would have been demolished long since. Ray writes of: ‘… the Queen Victoria Markets building in George Street. near the Town Hall. Don’t you remember it? A hideous bastard Byzantine structure with an immense green dome. It still stands but there is frequent talk of tearing it down.’

Ray’s letter was never intended for publication. It is a racily paced and candid picture of Sydney life and personalities written in no particular order: ‘I have just re-read this long letter and it seems to me to be terribly amorphous, discursive and disconnected.’ Ray adds that: ‘it does not have much information, I am afraid, that will be of any use to you. Most of it seems too scandalous and libellous. If as you say in your last letter, you intend to quote me verbatim, please be careful! Remember I’ve got to live in this damned place.’ Ray frequently warns Jack about the 1958 Defamation Act, for after its passage it is possible in this country to be sued for libelling the dead.

Ray forgot to be careful when he wrote in vitriol of P.R. (‘Inky’) Stephensen after his return to Australia. Jack either did not regard much of what Ray told him as a part of his own autobiography, or else he heeded his brother’s warnings about PRS’s litigious proclivities; instead, he quotes Stephensen in a footnote (p. 735, Penguin edition) giving Inky’s own short account of his return to Australia, his involvement with the Australian First movement, and his internment during World War II. Ray’s comments on Stephensen, and also on Christopher and Anna Brennan, are the most important parts of his letter.

Douglas Stewart remembers Ray in the 1940s (Norman Lindsay, Nelson, 1975): ‘... a feckless wild dissipated good-natured utterly likeable fellow with a red nose and a face like a potato, with the characteristic Lindsay volubility and loud barking laughter. Sometimes he and his father would paint from the model together ... but [Ray] never really settled down to work and died early of tuberculosis. “They’ve got no stamina, those boys” said Norman severely when one or another of his sons died, Ray or Philip, I forget which. It was typical of his refusal to indulge in what he called “false sentiment” but… he was fond of Ray and Phil… and what his real thoughts on their early deaths may have been no one will ever know.’

John Arnold, the editor of the letter, in an introductory section says, ‘Although derogatory of several people, especially women, it must be remembered that it was written as a private letter and in a period of antifeminism’, thus alerting a few early reviewers to voice disapproval when Ray refers to ‘bitches’, ‘wenches’, etc., but not to comment on some of the exceedingly coarse things several of the women in question are reported to have said to or about men!

I find this inconsistent, naïve and ignorant historically. Works that concern past eras must be considered in the context of their own times.

Low life and Bohemian people and places are central to Ray Lindsay’s account. He is not writing of La vie de Balmain or Carlton two decades after his death, but of a very small subworld of Sydney in 1920s that liked to think of itself as ‘roaring’ or ‘flaming’. Nowadays utterly conventional suburban mothers and their daughters drink in hotel bars and licensed clubs and take such relaxation for granted. In the 1920s respectable Australian women simply did not visit even well-conducted hotel bars, let alone the raffish wine shops and other places Ray describes. (Exceptions might be the wives of an occasional Bohemian like Jack Lindsay’s wife Janet but when Ray speaks of Janet in a ‘dive’ she is always in her husband’s company.)

The women who did frequent low dives, no matter how talented and interesting few of them were, and how creative and intelligent a few of the male habitues, were almost by definition not respectable. Every age has its words for them – Ray and Jack shared the slang of their times. Ray’s account does not mince words or suppress incidents concerning these girls – Christopher Brennan’s beautiful doomed daughter Anna was by anyone’s interpretation a loose woman. Also, according to Ray directly, and Jack more circumspectly, she was the object of Brennan’s incestuous passion.

Jack who could not admire Anna as greatly as did Ray said of her, ‘she oppressed me as too luxuriously blonde and strong minded, despite her angelic smile. . . and the fact that she was buyable hedged her round, as far as I was concerned, with an inviolability. Not that I ever tried to find out the exact line between her caprices and her finances’ (Life Rarely Tells, Penguin, 1982).

Lindsay’s sons did not inherit heavy drinking and wild wenching from their father who was a virtual non-drinker and too busy with work to bother with promiscuous affairs. The public of course believed he had passionate episodes with all the models for those lusty paintings and etchings. The public was wrong, except that his long second marriage was to Rose Soady, one of his chief models before and after they wed.

Rubery Bennett, painter and gallery owner, in The World of Norman Lindsay expresses what he calls ‘Norman’s philosophy in a nutshell’ and in doing so gives some of the reasons why the man who worked with myth has become one. ‘Norman said to me one day, “I am not interested in portraying womanhood narrow hipped and flat chested. I am only interested in portraying the woman who is the mother of the race”.’

‘... If, as Norman once said to me, we live on a planet called earth which exists for a reason that man tries to define and it produced life by some process unknown to man and it is reasonable to assume that the earth exists to produce life, then the greatest physical function of life is to produce life. The greatest mental function is to create; sex is creative, so the intellectual mind must worship sex as it is the basis of creation.’

Comments powered by CComment