- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Embrace all these experiences

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Migrant writing in this country isn’t just burgeoning, it has begun to flourish. The writing itself and the study of it begin to look like a ‘growth industry’. What I know of it is varied both in kind and quality, but I’ve no doubt at all that the poetry of Dimitris Tsaloumas is an important achievement by any standard.

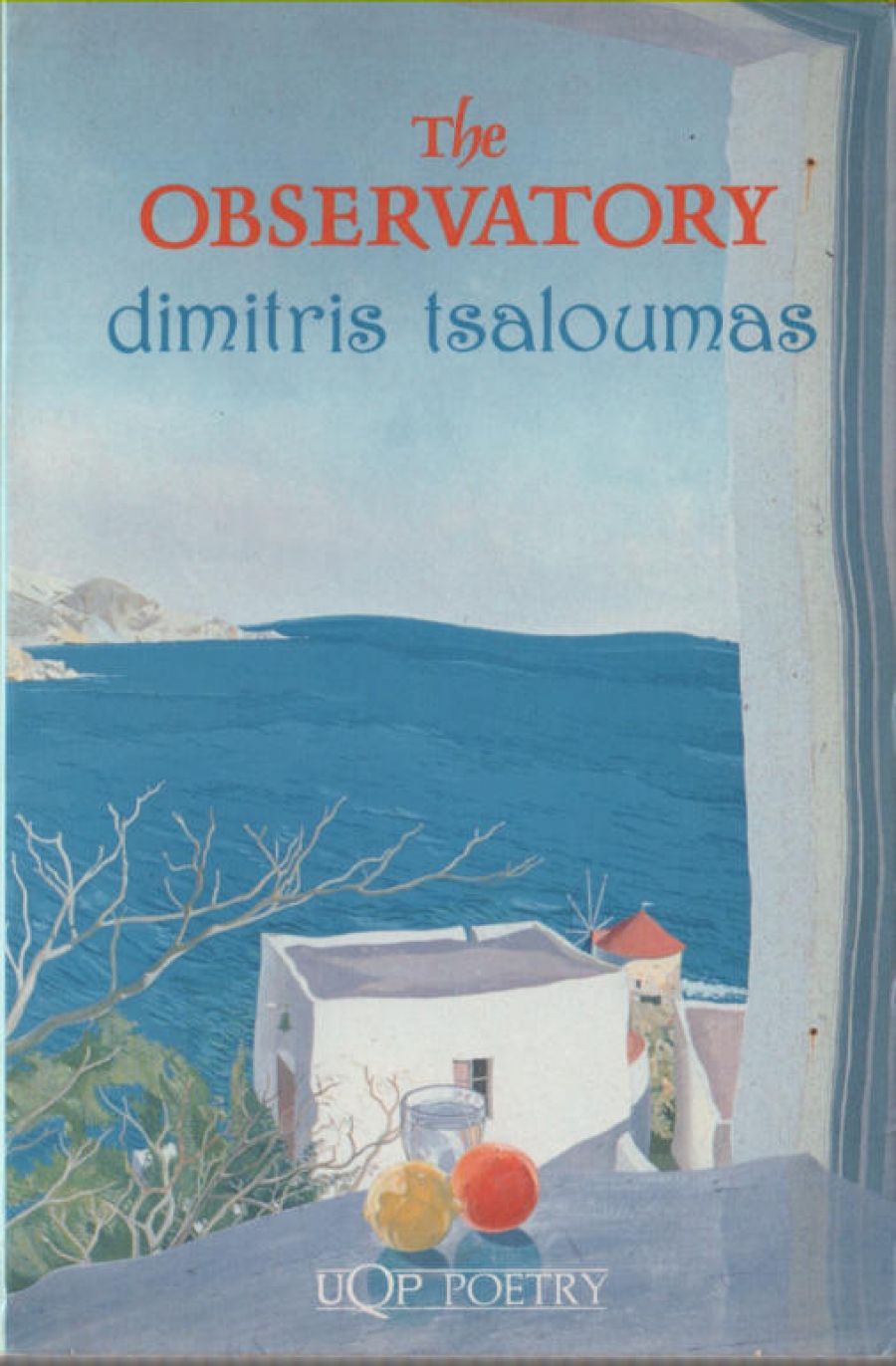

- Book 1 Title: The Observatory

- Book 1 Subtitle: Selected poems

- Book 1 Biblio: UQP, $14.95, $7.95 pb, 169 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/the-observatory-dimitris-tsaloumas/book/9781761280986.html

It’s a reminder, too, that Australian migrant literature is multilingual. Tsaloumas is one of many writers who, in Antigone Kefala and Ania Walwicz for instance, work here in their original languages. He came to Australia in 1952, having already published in Greece, and all the poems in The Observatory were written here. Yet he and I had lived in the same city for thirty years before I encountered his work. In 1981 the Poets’ Union staged an ‘ethnic’ reading in Melbourne: eight writers took part, Tsaloumas was one of them, and the publication of this book is a direct and major result. To many of us it was obvious, as he read in Greek and then in Philip Grundy’s translations, that this was a poet of real stature. His book strengthens that conviction.

The publishers have, ‘for your convenience’, made it bi-lingual: Greek and English texts facing each other, as in earlier books by Vasso Kalamaras and others. This doesn’t, alas, add to my convenience, but a friend with fluent Greek tells me that the translations often capture the original rhythms astonishingly well. What’s more, and this does come from me, they are fine examples of verse in English. An earlier reviewer has thumped one passage as ‘translatorese’: well, to locate it he must have used his fine-toothed comb.

And in praising the translations I’m praising three people: not only Philip Grundy whose name appears above the title page and who has (in collaboration with the poet) done most of them, but also Margaret Carroll and Tsaloumas himself, the ‘M.C.’ and ‘D.T.’ who contribute several more. The important observation here is that, whoever the translator may be, one unmistakeable voice emerges. (A comparison with Cavafy, in most ways a different poet, comes to mind).

How to define this poetic voice and personality? First, there’s a sense of unity and diversity at once. Diverse the poems certainly are: in length, for one thing, they range from the six lines of ‘The Chill-room’ to the six pages of ‘The Sick Barber’ and the sequence ‘A Rhapsody of Old Men’, from which we have six poems of the total nineteen. Then, too, there’s the diversity of forms and of speakers, from shorter poems in the poet’s ‘own’ voice perhaps, to longer ones like the outstanding ‘Barber’ poem, where the attention is focussed on another figure, to dramatic pieces like ‘An Overseer’s Letter’: this last a striking dramatic monologue which starts with straight evocation of the late roman Empire and then moves to deliberate and daring use of anachronism.

Further, there’s a wide range of tones. From ‘Observations of a Hypochondriac’:

Take off him the informer’s gaze.

and from the lever thrusting the same thought

from temple to temple take away the barb

that gangrenes the brain. Fear alone

now inflates the lungs of the bottled-up spider.

Let the crime bring darkness to the culprit’s eyes

From ‘Morning Lullaby for a Sick Child’:

Sleep now the bells of heaven are hushed

and I’ll send for my mother …

in the hills where the thyme thrives

and in the butterfly glen where the dewdrop is born

to witness the nativity of colour.

From ‘The Panoply’:

to the messengers of need new releases

I’ll speak like those

who sing of love, my love, like those

who make a fool of fate.

And from ‘Consolation’:

to have held something in your hands

is worth the bitterness of losing it.

These mere scraps will suggest some of the range of emotion: appalling facts are presented, and so are things which quicken tenderness and wonder. At times, too, as in ‘The Holy Inquisition’, we get a tough, self-mocking humour.

Tsaloumas is a poet who can embrace all these experiences and more, and can make a whole of them. Like some other poets, Greek ones especially, he has a wide historical range: ‘Newspapers full of ghastliness’, and at the same time, from Constantinople:

from the gardens’ ageless cool

in the City you pillaged

the nightingale sends greeting.

This is no sentimental yearning for a beautiful past: the City, you notice, was pillaged. Nor does he get his ghastliness from the newspapers only. He’s witnessed some of it himself:

The war’s been over now for forty years

and you’ve still to take the enemy off the wire.

Who opened up his back so that his lungs hang out

from behind? Haven’t you tied of his shallow moans in a whole lifetime?

(‘The Return’)

Or this, on the town informer during the same war:

[you] stick your ugly mug against the pane

and my soul is wild with fear in the dim lamplight,

or when you you crawl up night’s hair

in the rumbling of the surf and the groaning wind

to put your ear to the chimney.

Most of these poems are emotionally demanding, as I discovered in reading some to an audience. And rightly so. This is poetry which shirks at nothing. Perhaps the strongest note is one not of sourness but of bitterness (a frequent word): a recognisable and honourable bitterness which goes back to the ancient Greeks. And in fact, one thing I prize here, as in Cavafy and other Greek artists, such as Xenakis in his Oresteia, is the sense of that unbroken, living continuity. For Tsaloumas the past is present. This persists in poems which make overt reference to the Australia he has adopted. Not in all of these, I must say, but certainly in such poems as ‘Message’, one of the thirty selections from The Book of Epigrams which end this present book. (For Tsaloumas as for Ben Jonson, an epigram is more than usual witty two- or four-liner: here it’s a pithy, formally strict piece of between six and sixteen lines). ‘Message’, sub-titled ‘Green Cape, New South Wales’, is a migrant’s ‘triumph of life’ poem: ‘Tell her that I’ve made up my mind today that I shall never die.’ The words are addressed, the poet tells me, not to Greece (as some have thought) but to his mother. As the poem ends he quotes a famous cry from Xenophon with the naturalness found only in those to whom the past is not alien, nor foreign in another hemisphere:

Tell her that her son came down to the spray-misted headlands

of the South and saw the onslaught of waves

huge as island hills and cried out

The sea! The sea! And tell her that he changed his mind.

She wasn’t mean-spirited. She’ll understand.

There are some poems which I find a trifle arid, ‘Text and Commentary’ being one, and some which, as R.F. Brissenden suggests, need explanatory notes. But it’s no mean tribute that the more I read this book, the richer and more rewarding it grows.

Comments powered by CComment