- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Theatre

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The twelve-month period which began in February 1982 saw an unprecedented growth of interest in Aboriginal drama in English, both within Australia and overseas. In that month, Jack Davis’s second play, The Dreamers, made its début in the annual Festival of Perth and was generally well received by the critics. Five months later, Robert Merritt’s 1975 play The Cake Man was revived briefly in Sydney, in preparation for its two-week season as an Australian representative at the World Theatre Festival in Denver, Colorado. So popular was it that tickets for the entire season were sold out in advance of the first performance, thereby breaking all box-office records for the festival.

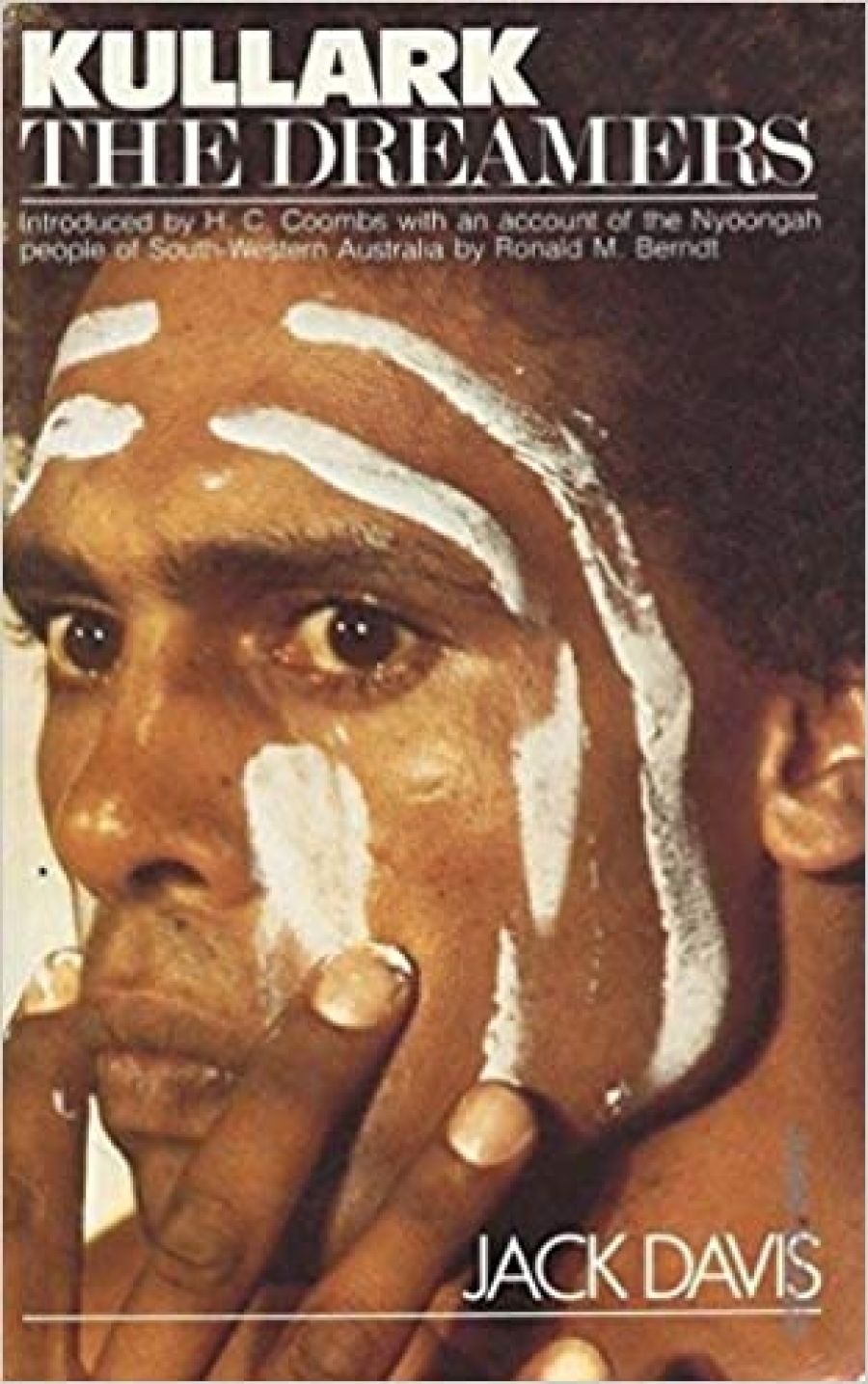

- Book 1 Title: Kullark / The Dreamers

- Book 1 Biblio: Currency Press, $6.95, 146 pp.

As a result of the enthusiastic overseas reception of the work – Merritt’s first and only play to date – The Cake Man moved directly to Melbourne upon its return to Australia, to enjoy a sold-out two-week season. After receiving further favourable publicity via a segment on ABC television’s Nationwide, The Cake Man was selected for performance in Brisbane during Festival ’82, in conjunction with the Commonwealth Games. Finally, there are reports, as yet unconfirmed, that the play will be adopted for the New South Wales High School Certificate syllabus in 1984.

While Merritt’s work has made the greatest international impression of any Aboriginal play to date, this is not likely to be the case indefinitely. For, in December 1982 Jack Davis’s two plays, Kullark and The Dreamers, joined it in print and were officially launched by Currency Press in Perth at the First National Aboriginal Writers’ Conference in February 1983. Indeed, firm plans are in train to bring The Dreamers on a full-fledged eastern states tour later this year. If past experience is any indication, it will not be long before invitations to perform the work internationally begin to arrive.

In view of all of the above, it seems incredible that in his review of the Davis plays in January 1983, John McCallum commented, ‘It used to be a maxim in the theatre (and may still be) that plays about Aboriginals don’t succeed’! As is frequently the case in the realm of Australian performing arts, it appears that international kudos is once again an essential prerequisite for domestic acceptance – and even then, does not absolutely ensure it.

As is also frequently the case, reviewers run the risk of distortion when they indulge in non-specific generalisations, as in McCallum’s assertion that ‘the dominant theme in Davis’s work, as in all Aboriginal literature in English in the last 20 years, is the search for a black identity for modern town-dwelling blacks’. Kullark, in particular, does not detail the search for an urban Aboriginal identity; it celebrates the distinctiveness, humour, and resilience of that identity. The poem with which Davis ends the work is a clear indication of this fact:

With murder, with rape, you marred

her skin,

But you cannot whiten her mind.

They will remain my children

forever,

The black and the beautiful kind.

In The Dreamers, too, where many despondent aspects of urban Aboriginal life are brought to the fore, Aboriginal identity is far from elusive. The ever presence of the Nyoongah dialect, the repeated framing of scenes with traditional Aboriginal music and dance, and the awareness of otherness which the young Black children of the Wallitch family possess, clearly indicate the continued strength of a separate sense of Aboriginality. As twelve-year-old Shane remarks to his white friend Darren: ‘I know what Wetjala [whitefella] is, that’s you’. And when his fourteen-year-old sister, Meena, is preparing to go out with her boyfriend, he counsels her to ‘watch it’, not for reasons we might expect, but because ‘he might be a relation, you know we got hundreds of ‘em’.

Both plays are, in quite different ways, celebrations: of family, of love, of tradition, and, above all, of Aboriginal uniqueness, humour, and endurance. There is realistic violence, sorrow and suffering in both, but Davis conveys such an honest tenderness in his Black characterisation that the sense one is left with at the end is bittersweet: a feeling of stubborn faith in the face of loss.

Kullark is far more of an occasional play. Designed for presentation during the Sesquicentenary celebrations of Western Australia, it relies heavily upon European documentary evidence for its historical perspective. In short, it portrays Black Australia for the most part within an overriding and impinging white framework: from first contact with settlers and soldiers to final contact with magistrates.

The Dreamers, on the other hand, comes far closer to being a totally Aboriginal play in setting, as well as in characterisation, music, and dialogue. The only real intrusions of the outside European world are the hollow, white hospital corridors at the beginning and end of the work, the white child, Darren, and various European characters seen through the eyes of the Blacks.

The Dreamers is definitely more foreign to European experience – and, in my view, is written far more for Aboriginal Australians – to the extent that the constant presence of the Nyoongah dialect causes the uninitiated to refer repeatedly to the glossary for assistance. (In fact, even the editors have occasionally come to typographical grief in their attempts to standardise the usage of the dialect.) For these reasons, White readers may find Kullark a more familiar and accessible piece of work. But, in my opinion, The Dreamers is worth the effort: it is the most culturally independent and autonomous Black Australian theatrical statement to date. It portrays urbanised Aborigines as they see themselves, without artifice, without embarrassment, and frequently with humour and lyrical sensitivity. In short, I feel it is the superior play.

Currency Press must be congratulated for their part in bringing the drama of Jack Davis into print and for reaffirming their commitment to the publishing of Black Australian playscripts. Above all, Jack Davis must be congratulated for his lucid portrayal of the fact that, in spite of what White Australians have done in the past, the Dreamers – and the optimistic realists – live on.

Comments powered by CComment