- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Science

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Frigid Fascination

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

While most of us know something of the great figures of the heroic age of Antarctic exploration, the more painstaking and routine, although often equally courageous, work of the scientific expeditions in the last fifty years rarely commands public attention. Dr Phillip Law, Leader of the Australian National Antarctic Research Expeditions from 1949 to 1966 redresses this neglect in the first volume of his autobiography, reviewed here by Clive Coogan, who assesses Law’s own contribution and the Importance of his work to Australia.

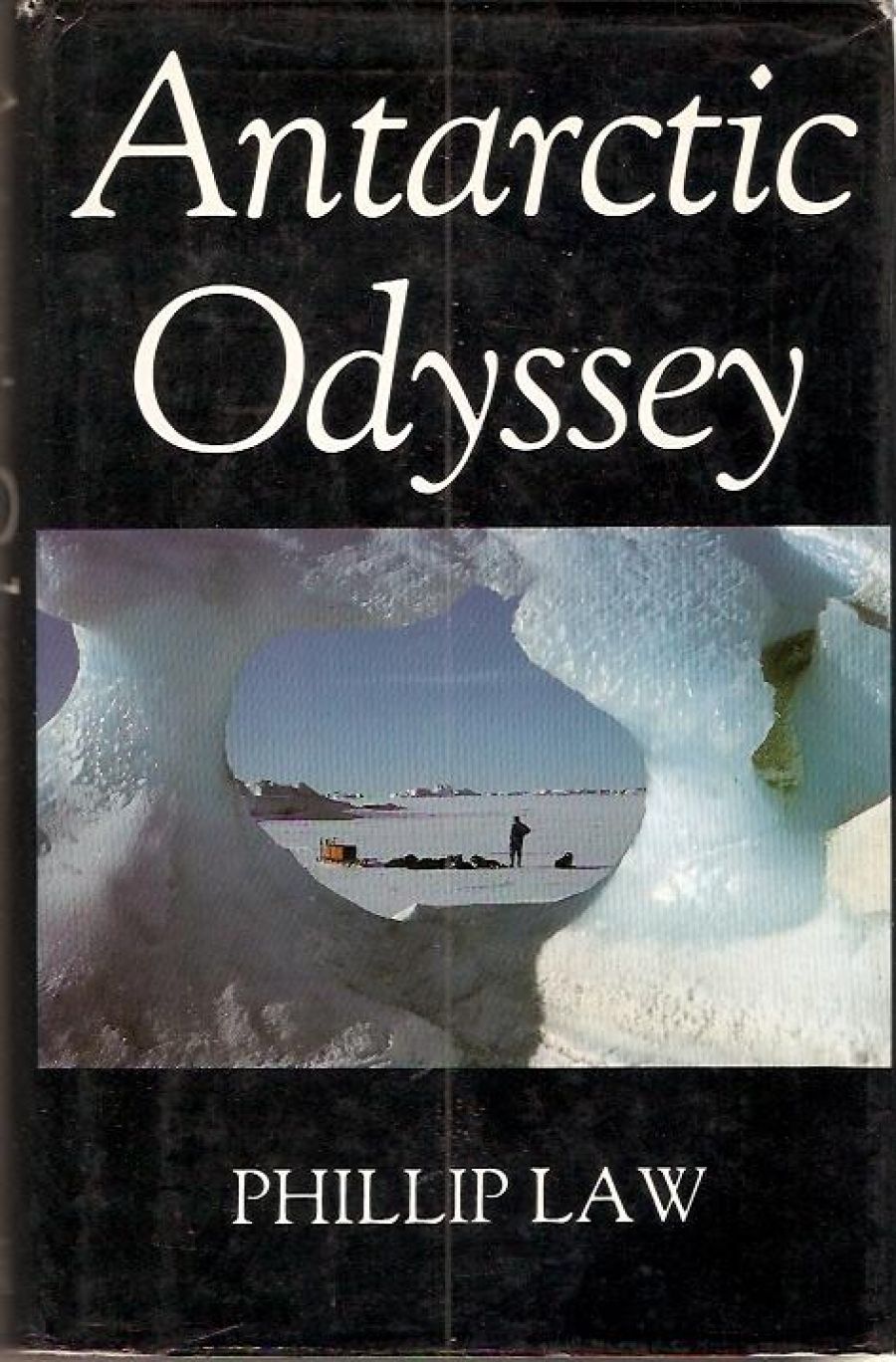

- Book 1 Title: Antartic Odyssey

- Book 1 Biblio: Heinemann, $35, 282 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Australia, the parched and scorched, has always had a peculiar love affair with the Antarctic, ‘that accursed land’ of the South. This is a perennial Oz summer fantasy, with ANARE ships leaving from North Wharf, Melbourne, every December, on the month. It turns out, under the analytical gaze of Science, that the Antarctic is an even drier continent than Australia, as many parts receive less than 4 inches precipitation per year.

This fascination with Terra Australis Incognita Frigidus seems to have started with Australia’s ‘discoverer’, James Cook, just 210 years ago, when he became the first man to cross the Antarctic circle, sailing within 75 miles of Enderby Land. Cook’s encounter with floes, icebergs, brash-ice, growlers and frozen sheets of ice for sails (which gloveless seamen had to furl) led to the formation of strong opinions, and a rapid retreat to the North with recuperation in an idyllic inlet in New Zealand. Quoth Cook: ‘I can be so bold to say no man will venture further South than I have done’ as he warmed to his description of the Antarctic ‘doomed by Nature never to feel the warmth of the Sun’s rays but to be buried in everlasting snow and ice’.

Until then, only a few other English men, like Admiral (‘Foul-Weather Jack’) Byron, the annexor of the Falklands and grandfather of the lyrical Lord, had braved these climes. Later multitudes followed them because the Antarctic ‘was there’. Excited by Cook’s descriptions of Cornucopian seal and whale populations, matter of fact business sorties followed until Amundsen, Scott, Mawson, Shackelton, Ellsworth and Wilkins took over after the turn of the century and brought the calendar up to WWII, leaving their epics traced in frozen blood.

Australia followed this inextinguishable urge to explore its great frozen neighbour as soon as possible post-war. Significantly Phil Law’s book glosses over the political urges and urgers that drove us to occupy our frigid heritage. He starts with a chance meeting between lecturer Law and Professor (later Sir) Leslie Martin in a corridor of the Physics Department at Melbourne University in 1947. Martin had returned from Canberra, and he knew that there was difficulty in finding the right man to lead post-war scientific exploration in the Antarctic, so he asked Law for suggestions. To Law, inveterate bushwalker, climber, and cross-country skier, this was a golden opportunity which needed to knock but once. For almost 20 years, 1947 to 1966, he directed Australia’s affairs in exploration, research and consolidation in the Antarctic. He may not have made the epic overland journeys of Scott, Shackelton or Mawson (although from the cosy depths of an armchair his exercises seem terrifyingly dangerous enough!) but he has left behind him a very firm basis for Australia’s future work down there.

This book is Law’s first about those days, and I hope that it will not be the last. It covers only one epic voyage to the Continent in 1954, to set up Mawson station in MacRobertson Land, in the Australian Antarctic Territory, to supplement the already established bases on Heard Island and MacQuarie Island. There is much more to be told, and if told as well as in Antarctic Odyssey it will be intriguing future reading.

I can vouch for Antarctic Odyssey being fine summer reading. Open it at any page and the body temperature dips several °C, and sand, sweat and flies recede. It is written in the spare lean prose of the scientist/administrator, in which the story-line dominates and the prose serves. This matter-of-factness heightens the drama, such as the ‘close-go’ of the Krista Dan in a hurricane – 100 mph winds, the boat heeling over to 70°, Law wedging himself into the bunk, the heart-beats of terror – and the relief as the storm dies away and even the most irreligious are thankful to Someone.

Law acquaints us with some odd aspects of sub-zero living. For example, just as his forerunner, Cook, found that the slothful cook, ‘Murduck’ (Murdoch, alias Mortimer) Mahoney was the most important member of the crew of his associate ship, the Adventure, and by neglect the murderer of many of the crew via scurvy, Law finds that his white army also marches on its belly, and that much thought had to be given to food and drink, and how these were served.

The astronomer Bayly, of the Adventure, writes a frank obituary of ‘Murduck’ in his journal: ‘died of scurvy being so indolent and dirtily inclined that there was no possibility of making him keep himself clean, or even to come up on deck to breathe the fresh air’. Cooks of the day were chosen on the basis of their uselessness for other tasks and never had full limbs four! Whereas Cook busied himself with anti-scorbutics, ‘sellery’, ‘krout’ and ‘scurvy-grass’ (when trips ashore permitted), two centuries later Law ensured that besides the pemmican, rolled oats, cocoa, dehydrated butter and salt and pepper (not unlike Cook’s provender) there were also vitamin pills.

Law leads us on an interesting tour around the psychology and psychiatry of danger, deprivation and incarceration with a small number of men, from whom there is no escape for a whole long winter other than via the Gatesian ploy! Careful choice of candidates, from a not unlimited offering, is paramount. How does one pick the bluffers, the phonies, the bludgers and the intolerably abrasive, and how does one lay off the obvious defects of a man against his plusses? But dealing with a petulant and often irrational Captain Petersen of the Krista Dan is another matter, with no element of choice. Yet Law presents a picture fair enough for us to appreciate Captain Petersen’s motivations and concerns also, and in the chronicles of their frequent conflicts Law balances the account with a picture of wary cameraderie enforced by common dangers and common concerns.

The constant plaint of the front-line troops about the defects of the back-up from Blighty comes through strongly, perhaps better documented than usual, because Law was au fait with both the privations and the privy councils, and does not hesitate to slot the blame into the pigeon hole where it belongs. The rusty magnetometer, with futile hopes of operation, and later the unoperational gravity meter bring down curses on the workshops of the Bureau of Mineral Resources. The accounting and procurement sluggishness of the Services, on the other hand, evokes wonder at how these bodies can function in the face of such ‘assistance’. The gaucheness of the Public ServiceBoard and the strictures of the Treasury produce blank amazement. ‘The cost of feeding a migrant in a hostel in Canberra is half that of feeding a man in the Antarctic’ was the intellectual gem proffered by one Treasury dolt; whereupon Law walked out. I would like to have been there!

But why take the trouble to explore and research in the Antarctic? Who knows? It is the scientist’s equivalent of Hillary’s ‘because it is there’. Science and Technology Minister, Barry Jones, has himself seen the light and tells us on his return from his recent trip to the Antarctic that American scientists studying seal pups think that they have stumbled across the key to the infant cot death syndrome (in a place devoid of infants!), and others have thrown conventional medical wisdom into dissarray with the observation that members of wintering parties have contracted measles long after the traditional incubation period is over. Broadly the research goes on because it is an unexplored area, and who knows what the spinoff will be?

This is a good book; it is both a ‘good read’ and a scholar’s resource book for the future. I hope that Phil Law will produce more, and put down for posterity such yarns as ‘The White Wines of the Antarctic’ which so fascinated the CSIRO Society for Ingestion and Pontification (CSIRO SIP) some years ago. The book is well produced and sports some excellent colour photography, a good deal taken by Law himself.

Of course, being only a human product the book has some flaws. To show that I was awake whilst reading it, I doubt that the special, Swallow and Ariell ‘Sledge Biscuits’ are inch think’, or that ‘sent’ of page 36 is a suitable substitute for ‘send’. Then there are some repetitions, due no doubt to writing the book in parts, which could have been pruned.

I believe that this 1954 odyssey will probably prove of more lasting value to Australia than the seven voyages of 1983 around the buoys off Newport, Rhode Island, of Australia II. Read it and judge for yourself.

Comments powered by CComment