- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the penultimate chapter of his memoir, Bernard Smith describes a meeting of the Sydney Teachers College Art Club, an institution he founded and later transformed into the leftist NSW Teachers Federation Art Society. The group was addressed in 1938 by Julian Ashton, then aged eighty-seven and very much the grand old man of Sydney painting and art education. He spoke at great length on the inadequacy of the NSW Education Department’s art teaching practices. Smith adds that Ashton also ‘told his life story (as old men will)’.

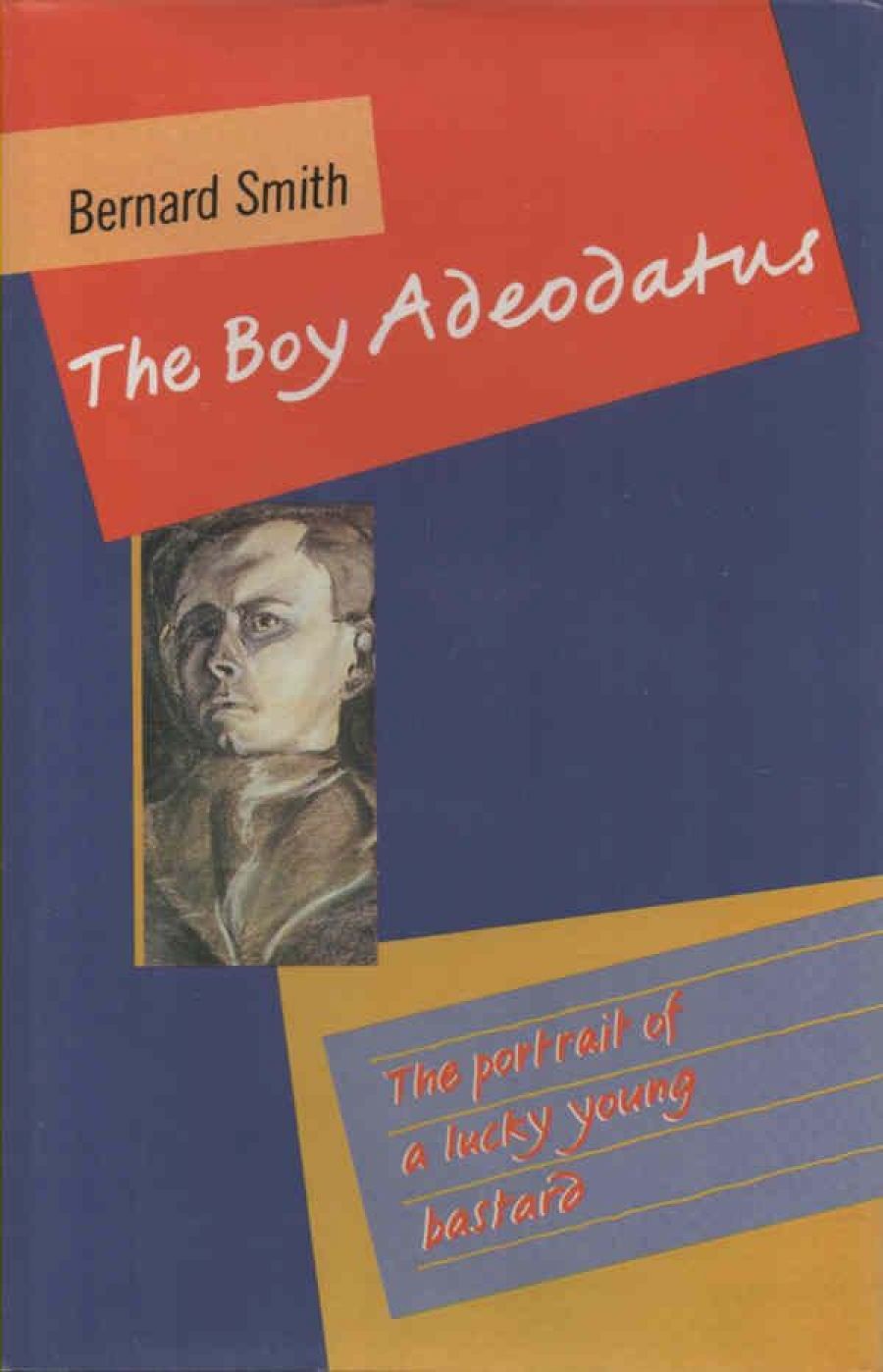

- Book 1 Title: The Boy Adeodatus

- Book 1 Subtitle: The portrait of a lucky young bastard

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen Lane, 302 pp, $19.95

As the wry parenthesis suggests, Smith is knowingly doing something similar in this book. Autobiography becomes polemic, and vice versa. Smith is both the narrator and subject. Sometimes the cultural historian Smith leaps out from the page, telling readers how much they missed when he, the subject, forsook painting for art education. He peevishly complains, too, that ‘the influence of Federation Art Society lectures has been completely ignored by historians of modernism in Australia’.

But there is never any doubt that Smith, now in his late sixties and a retired but prolific art educator, enjoyed putting this elaborate self-portrait together. The book ends when he was about twenty-six, after a number of decisive experiences and events.

One event which closes the book is Smith’s immersion in the cultural wing of the Australian Communist Party. He joined the party in 1939 or 1940 (the dating isn’t clear) and remained a member for four years. Another event which helps to round off the book, and is much anticipated, is his loss of virginity. Yet another is his decision, after some years seriously pursuing it, to abandon painting for the vocation of the art educator.

We are not told whether Smith later resumed painting or regretted his decision. It should be said that this is not a rueful autobiography of a painter manqué but an indictment of a culture manqué. Nor are we told how Smith now regards his career as a teacher devoted to building a sophisticated knowledge and appreciation of art in Australia.

A less ambitious, more conventional autobiography might have answered or broached my literal-minded questions. Smith distances himself, I think over-distances himself, from conventional personal memoirs. The Boy Adeodatus is something like an historical fiction, in fact, told in the third person by a magisterial, cunning narrator.

As a contribution to that rich Australian genre, the part-autobiography of an intellectual, artistic, literary or otherwise ultra-sensitive young man, this book is powerful but eccentric. Fortunately, it is unlike so many examples of the genre which see childhood in idyllic, pre-Freudian, innocent terms. While Edenic images of gardens in suburban Sydney and central Queensland, amongst other places, abound, Smith’s childhood starts with the Fall. And he sifts the soi-disant ‘raw material’ of childhood remembrance through a host of aesthetic, psychological, sociological, and metaphysical theories acquired on the road to maturity. Indeed, it is the fusion of otherwise mundane materials with a metaphysical conceit which makes this book both charming and maddenly confusing for the reader.

At another level, much of this book is a remarkable contribution to the social history of intellectual communism in Australia in Smith’s given period. He was one of a small band of artists and art connoisseurs who joined the party at a most unpropitious time, during the ‘phoney war’ in World War II, in advance of the much larger movement by young intellectuals into the party during the wartime and postwar years.

The ultra-modernism espoused by Smith, according to The Boy Adeodatus, seems discontinuous (from my memory) with the critical realism he espoused in Place, Taste and Tradition (1945), his first book, which was evidently the product of four years working in the Communist Party’s cultural wing. A further volume dealing with the war years and the onset of the Cold War would make fascinating reading.

This book is equally valuable as a contribution to the social history of childhood, or childhoods, in Australia.

It is a deeply moving account of an illegitimate child’s search for a ‘servicable identity’ (his term) and a perplexed tribute to ‘all those mothers and fathers who had nourished him’.

Smith was indeed a ‘lucky young bastard’, since he was not adopted in the manner which deprives a child of knowing his actual parents, or even knowing the fact of his illegitimacy. He spent the first nine months of life with his mother, and remained in contact with her after he was fostered or ‘boarded out’ with a remarkable family in the Sydney suburb of Burwood (then an outer suburb).

One of the few clear advantages of Smith’s choice of the third person is that he can better depict his fluid identity as a child and adolescent. In one family he was Ben or Bennie; in the other Bernard or Bernie. In one he was presumed to be Catholic, since he was baptised as such. In his foster family, which was essentially Congregationalist and Christian Socialist in the Charles Kingsley vein (‘Tottie Keen and her water babies’), he was nevertheless sent to a Salvation Army Sunday School! In adolescence he attempted to ‘return’ to his ancestral Catholicism, but failed. There are some wonderful lines in this book about the religious appeal of the Communist Party.

One incidental feature of Smith’s upbringing is that his rather large network of relatives, natural and adoptive, gave him a knowledge and experience of a variety of parts of Australia, and of Australian social types, which few Australian children could acquire today. The sociologically circuitous manner in which he arrived at an artistic-pedagogic vocation is one of the many fascinations in this book.

Moreover, Smith is able to present himself in a distanced way partly because of the survival of his foster-mother’s collection of letters, his continuing communications with his mother, and his own diaries. And as a ‘State kid’ he has the advantage of an ‘identity’ which is bureaucratically documented in files.

The third-person narration gives Smith great freedom to detail the predictable and unpredictable relationships between ‘the personal and the political’. This is most marked in his brilliant formulation that ‘the very illegitimacy of Communism within the tainted legitimacy of Australian society gave it [the party] for him a certain sanctity’. As the book proceeds towards crucial decisions which conclude he subject’s childhood, Ben/Bernie becomes increasingly a didactic plaything of social and historical forces. There are perhaps too many authorial interventions of this kind: ‘Events on all sides were conspiring to radicalise his views.’ At times one suspects that too much retrospective knowledge is imposed on certain childhood incidents or turning points.

The problem of the narrator’s intentions really becomes acute as one tries to understand the point of the analogy between Ben/Bernie and the boy Adeodatus, the illegitimate, precocious and beloved son of St Augustine who died young, at the age of seventeen. The key relationship in the text is between Bernard and his actual mother; his actual father, Charlie Smith, took little interest in him and was far from saintly. One possible reading is that Ben/ Bernie spiritually died when he failed to ‘return’ altogether to the Catholic Church, and eventually embraced communism. It could also be that conversion of communism was a kind of spiritual death, but in this case the point of the analogy lies beyond the time-span of the book.

Smith’s habit of inserting frequent quotations, mostly from St. Augustine’s Confessions, into the text, in italic, also complicates the matter, suggesting an identification with St Augustine himself. Most of the quotes are correlative or corroborative, after all. But it is also possible that St Augustine represents an idealised but absent father (Charlie Smith), with whom Ben/ Bernie could have engaged in profound moral dialogue, as Adeodatus was made to do in St Augustine’s De Magistro.

To illustrate the playfulness, if not the projective chaos, in which Smith the author approaches the matter, there is the instance of one insistent prayer. Twice Smith has Ben/Bernie uttering or thinking ‘O God, keep me chaste for yet a little longer’. St Augustine’s famous prayer, on the other hand, was ‘Give me chastity, but not yet’.

It may be that readers more familiar with allegory, or even with allegorical painting of the kind which the young Bernard Smith executed and then abandoned, will find the Augustinian conceit in this text more plausible or more meaningful than I did. While I found the book gripping, a profound work of autobiographical art, it is also a work of overweening artifice.

Comments powered by CComment