- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: War

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Leading the troops

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

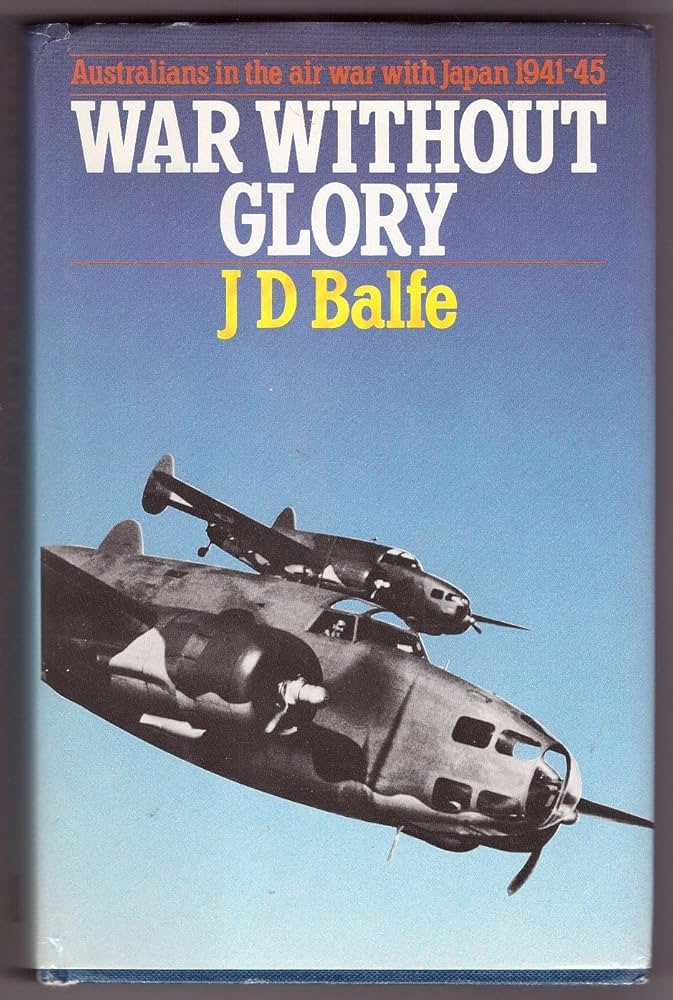

These books have little in common though they are both concerned with men at war. Balfe’s book is chatty, idiosyncratic, episodic and without any academic intent. Often using the words of three pilots involved, he tells the story of the futile and costly air fighting which followed the highly successful Japanese attacks against Malaya, Sumatra and the Netherlands East Indies. Australian aircrew were forced to fight the Japanese with Hudsons and Buffaloes. Given that the enemy had overwhelming superiority in numbers; that the Buffalo was one of the worst fighters produced, and that the Hudson was no match for virtually any Japanese aircraft, the Australian squadrons after the initial contacts were almost completely destroyed. The causes of this disaster and the eventual outcome of it are well known.

- Book 1 Title: The Commanders

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, 356pp., illus., index, $29.95 0 86861 496 3, 0 86861 504 8 pb

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: War Without Glory

- Book 2 Biblio: Macmillan, 294pp., illus., index, $19.95 0 333 35677 2

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Balfe adds nothing to the outline which is not in the official war histories, his only general sources. However, if one would like to try and feel what it was like flying inadequate aircraft against the superb Zero, then this book has definite value.

The last section of Balfe’s book is also interesting. In fact, one wishes there was more of it. The third person is dropped, the writing becomes autobiographical and he is concerned with his experiences as a trainee flying instructor enlisted under the Empire Air Training Scheme and then as a C-47 pilot operating from North Queensland and New Guinea. Memoirs of Australian aircrew in the Second World War are scanty. Perhaps this is surprising given that over 37,000 were trained under the Empire Air Training Scheme. As time passes, much of the detail of this enterprise will be lost. It might be hoped that Balfe’s book will encourage other to tell us what it was like. After all, a lot happened to a great many of them.

War Without Glory is thus essentially about those who saw the ‘sharp end of war’. The Commanders, as one must suspect, is about those who committed the ‘common soldier’ to battle or who administered the armed forces in time of peace Eleven contributors between them have presented sixteen studies ranging from Major-General Sir William Bridges who commanded at Gallipoli to General Sir John Wilton who ended his career in 1970 as Chairman of the Chiefs of Staff Committee.

It is a most successful endeavour and much of the credit must go to David Horner himself. The authors were chosen with care. Either they knew their subject personally or had previously written about him Moreover, Horner’s introduction is a model, a result one imagines of a lot of hard writing. Running through each of the studies are a number of well defined themes. What, for example, are the qualities required for command; how did they respond to what Clausewitz calls ‘friction’ or ‘pressure’? Has there been a particular style of Australian command and how has that command been exercised under both British and then American more senior commanders? Naturally the book is mainly concerned with the Army, though Stephen Webster writes well on Vice Admiral Sir William Creswell as First Naval Member while Harry Rayner underlines the political qualities of Air Chief Marshal Sir Frederick Scherger.

In a book of this type, it always seems unfair to single out any contributor for praise. More so, perhaps, in this volume: it has a cohesion which could only be the result of first class cooperation between editor and authors and among the authors themselves. All reach a high academic standard while remaining most readable by the interested layman. Again, both David Horner and the authors are to be congratulated in performing this often difficult task.

What cannot be done, however, is to make most of these selected commanders likeable or attractive personalities. Bridges was the worst kind of egotistical martinet. Guy Verney mentions that Brudenell White was “untiringly loyal” but fails to note that this loyalty probably only extended to his own class. After the war, he devoted much time and thought to the creation of the ‘White Guard’ apparently devoted to keeping some lower socio-economic groups in order. Monash, at the hands of Peter Pedersen, emerges as a superbly efficient divisional and corps commander. Yet it was only after he left the army with all his honours that his essential humanity overcame his craving for power and place. Lavarack had a “fiery temperament” and was another jealous for recognition and honours. Gordon Bennett was not only quite impossible as a person but as a commander as well. Moreshead was another “martinet”. Herring was “implacably competitive" and possessed a “blue-glacier glare”. Wilton had an “emotionless exterior” and earned the nickname ‘Happy Jack’. There is, in fact, little show of humour in any of them: not surprisingly, their portraits are unsmiling with the mandatory military moustache above their tight lips.

It could be argued, therefore, that while this volume is an excellent addition to the small but growing number of studies in Australian military history, there is much more to be done which will help us to understand such people. We need to know more about the sociology of service institutions and the psychology of those who hold command within them. In the past, some rather flawed personalities have risen to high rank and with it have assumed awesome responsibilities. One feels that it is different today, but we need to know. After all, it may have been commanders of the type mentioned who were responsible for the tragedy which befell Balfe’s young men.

Comments powered by CComment