- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

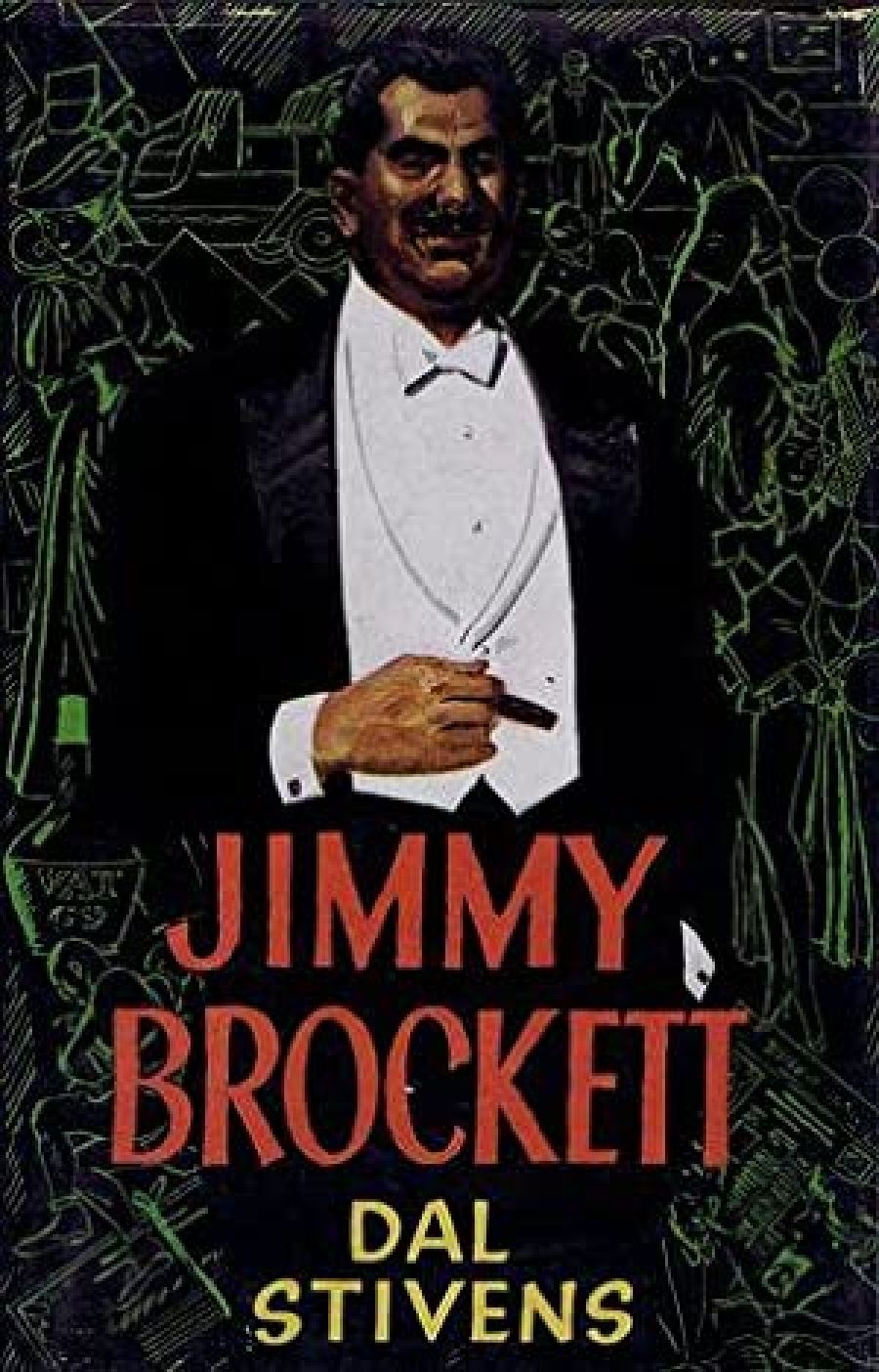

First published in 1951 and again in 1959, Dal Stivens’s novel, Jimmy Brockett, is now republished as one of Penguin’s ‘Australian Selection’. Reading it, you find yourself being drawn into admiration of a man who is undeniably obnoxious.

- Book 1 Title: Jimmy Brockett

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, $6.95 pb, 257 pp

None of this is offered in a comical way; Jimmy Brockett is not simply a likeable rogue. And yet one finds oneself entertaining a deeply sympathetic interest in his affairs, and even their success. It’s largely the result of Brockett’s being allowed to tell his own story in the first person – and not from some safe, more enlightened point in the future, but virtually as the events happen. He tells it in his own language. Crucial, this, for the raw vigour and confidence of his language express the man’s character in a peculiarly direct way, just as they continually stave off his (and our) questioning of the morality of his business dealings. His racy Australian vernacular (‘Busy as a bob-tailed calf in fly time’; ‘Sadie had me by the short hairs’; ‘If they breathed up and down instead of sideways, maybe I could pack two thousand in the Australian Sporting Club’; and so on)-this kind of language allows him unconsciously to distort the motives of his opponents and the needs of his wife and girlfriends into something amenable to his imagination. The characters have a shadowy existence as a result because we get only as much as Brockett can conceive of them. At a number of points he momentarily recognises qualities outside his ken: self-sacrificing love, genuine political principle, the artist’s dedication: ‘I’d been knocked kite-high but for some reason I couldn’t say very much.’ But he always withdraws from the abyss. The ‘bright ideas’ start tumbling out of ‘the old think-tank’, and the show is on the road again.

Reading this novel sympathetically means accepting Brockett on his own terms – that is, in the terms of his language. My guess is that some readers will refuse to. But those who don’t refuse will be rewarded with insight into the mind of the big-time con man, the unscrupulous entrepreneur: what keeps him going, the fertility of his cunning, the inventiveness and energy of his scheming mind, its self-justifying momentum, how he depersonalises people into pawns – how he is and does all these things while remaining recognisably human. Stivens’s portrait of the con man is of a lived occupation: it has weight. Stivens doesn’t belittle or schematise. The inspired choice of the first person narration allows him to grant Brockett a full measure of sympathy.

Less happy are the interspersed anecdotes and newspaper extracts – all in the third person and italicised – which are partly intended to strike an admonitory note, reminding us, like a tolling bell, of the vanity of Brockett’s endeavour. It’s as if Stivens is trying to salve his conscience while writing a fascinated (and fascinating) portrait of a man with no conscience-a representative Australian robber-baron.

Comments powered by CComment