- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

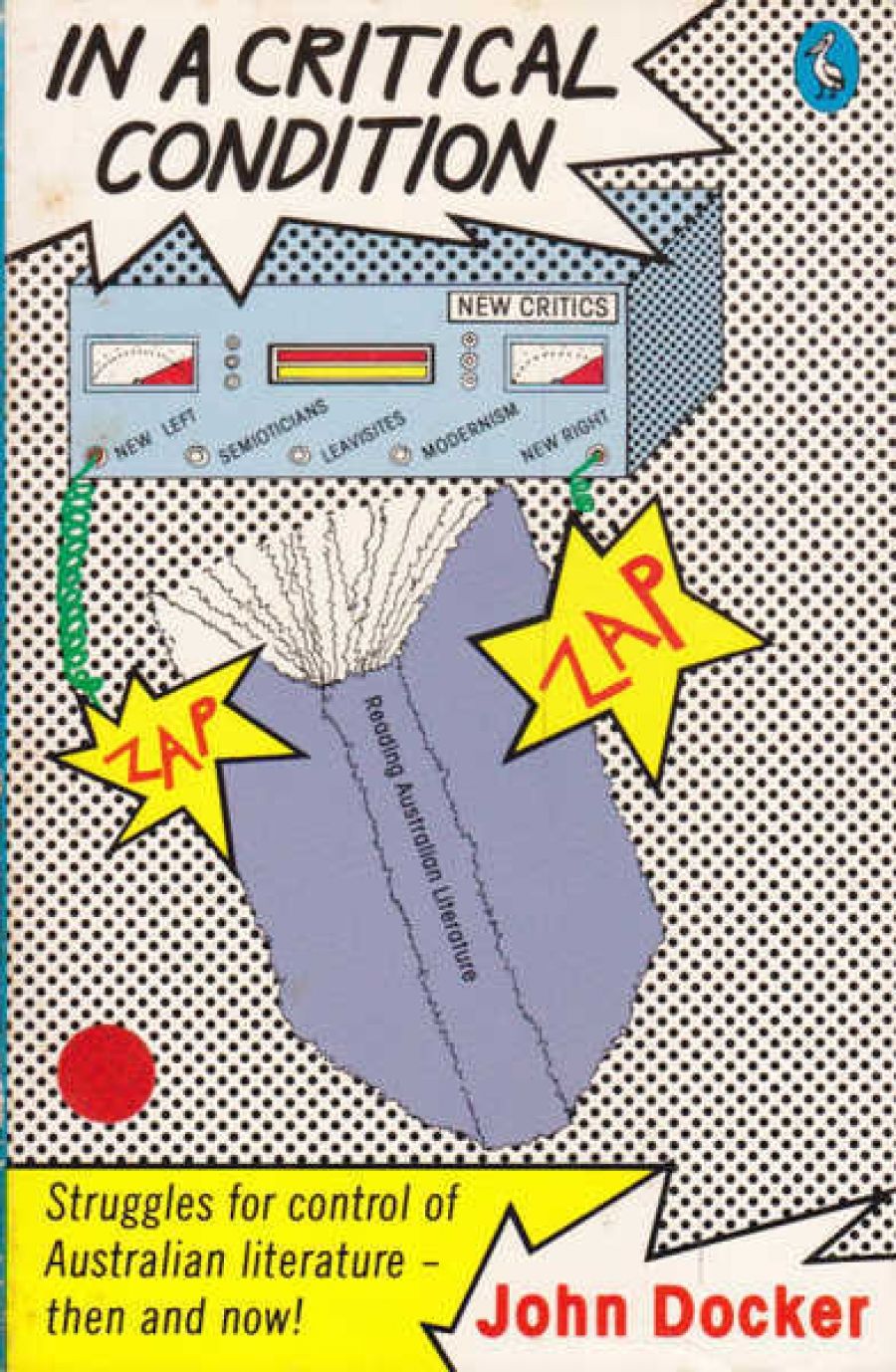

John Docker has written an entertaining if uneven book on the history and politics of literary criticism in Australia. The subtitle of the book, ‘Struggles for control of Australian literature-then and now!’ along with the Pop Art cover, gives an indication of his combative and slightly melodramatic approach. The book is, however, extremely important and something of a landmark. It presents a broad overview of the institution of literary criticism and its teaching in Australia, especially during the 1950s and 1960s. It discusses the political implications of various critical methods, and draws attention to some of the wider social and political ramifications of what occurs in the English departments of tertiary institutions. There is also discussion of the work of individual writers such as Katharine Susannah Prichard and James McAuley. As Humphrey McQueen writes in the foreword to the book, ‘His work also deserves the attention of people whose first area of interest is not literary criticism, for example, anthropologists, historians and political scientists.’

- Book 1 Title: In A Critical Condition

- Book 1 Biblio: ' by John Docker

Broadly speaking, Docker identifies two main Australian critical traditions. He argues that the first, the radical nationalist tradition was gradually displaced by a metaphysical ascendancy (Leavisites, New Critics) which then became the dominant orthodoxy. This orthodoxy has recently broken down.

The group who staked out their territory first were the radical nationalists – (Nettie Palmer, Vance Palmer, A.A. Phillips, Stephen Murray-Smith, Ian Turner, Russel Ward, Geoffrey Serle). They are, according to Docker, the most influential school of ‘contextualists’ in Australian cultural criticism. Their ideas are an Australian variant of ‘historicism’, a view of society that is against the idea of general laws of development. Each society is the result of a set of unique influences. For the radical nationalists, Australian society was the result of a combination of several unique factors, the decisive one being the bush and its effect on the people who tried to live in it. Australian society had its own special and defining character.

In their literary criticism, the radical nationalists highlighted those elements within Australian literature that demonstrated what they saw as representing a truly distinctive Australian character and voice. They tended to locate the authentic Australian culture within the context of the bush. The city was regarded as essentially corrupting and alien, a repository of false values. They also sought a unity between culture and natural environment and as a result were attracted to what they believed Aboriginal society had achieved. The Jindyworobaks were one example of this.

The main difficulty with their approach to culture and literature was their belief that each age and society had an essential spirit. This plays down the actual diversity and conflict within society at any one time and leads to a situation where only those works that express the essential spirit are seen as having value. Works that don’t, for whatever reason, are accorded only marginal status. The other difficulty was a tendency to see the development of literature in terms of a progress leading to a specific goal, in this case, the expression of the authentic Australian character and voice.

The Australian New Critics and Leavisites (G.A. Wilkes, Vincent Buckley, H.P. Heseltine, Leonie Kramer, Leon Cantrell) came to the fore during the 1950s and 1960s. This metaphysical ascendancy, as Docker calls it, can be traced back to the rise of modernism and its attendant criticism in Britain and America. The major British influence was Leavis. On the American side there were a number of influential figures, the most important being John Crowe Ransom. An important though in some ways isolated Australian precursor was James McAuley.

Docker’s discussion of the international context is the weakest section of the book. It lacks depth because it ranges over such a wide area. The discussion of the ideas and influence of such figures as Lionel Trilling and Frank Kermode reads a bit like a caricature. To a certain extent this doesn’t really matter, for its does not affect his main argument that, despite local differences, these critics, British and American, shared a set of common assumptions about the nature of literary criticism which eventually became the orthodoxy.

This orthodoxy, this new critical regime, was essentially a concentration on the text to the exclusion of such extraneous elements as the author’s biography, his intention, the historical and political context … in fact anything outside the text. The first law of criticism, according to John Crowe Ransom, ‘is that it shall be objective, shall cite the nature of the object,’ and shall recognise ‘the autonomy of the work itself as existing for its own sake’. Docker argues that the effect of this approach was to undermine the social relevance of the work, to subvert its relationship with the wider social context. The result is that works of literature no longer become, or can legitimately function as, vehicles of social action and change. Consequently this orthodoxy served the ends of those who wanted to maintain the cold war by rendering literature politically impotent.

The Australian New Critics and Leavisites introduced this formalist criticism into Australian universities and established a control over the teaching of literature in those institutions. Like their counterparts overseas, there were local differences between them, but they shared a set of common assumptions and participated in the erection and maintenance of an orthodoxy. Thus, according to Docker:

Students and teachers absorbing critical approaches and developing their skills in the 1960s and ‘70s in departments of English have been subject to a continuous process of institutional repression.

This ‘repression’ consisted of a promulgation of a canon and a critical approach. Other approaches such as the contextualism of the radical nationalists were discouraged as having little relevance to the true task of criticism. Key writers were either excluded from the canon or, as in the case of Xavier Herbert, brought in, but in such a way and on such terms that the meaning of their works, or at least one set of meanings, was subverted.

This orthodoxy has recently broken down and Docker argues that the authoritarianism and dullness of The Oxford History of Australian Literature is evidence of this. There is now no hegemony of formalist criticism, but the advent of structuralism, semiotics and deconstruction suggests that a new formalist orthodoxy may be in the process of asserting itself. He attacks the French critic Roland Barthes and his book, S/Z on this basis, regarding him as a sort of reincarnated New Critic.

Throughout his book, Docker is constantly alert to the dangers of relying too much on the context when approaching a literary work, just as he attacks formalist approaches that will not go outside the text. He proposes, inevitably, an alternative, a criticism that can take account of the context in the widest possible sense while remaining mindful of the demands of the text itself. This is okay so far as it goes. The problem is that it is vague. Yet, despite this, the point he is making is valid and important. Too often criticism, formalist or otherwise, narrows the range of readings available in a text by narrowing the range of legitimate responses.

Docker proposes a more inclusive criticism than we have had so far. It is an open question as to whether such a criticism is possible, or even desirable. ‘Without Contraries is no progression,’ said Blake in another context. In one sense Docker’s book frames the question of what is possible in literary criticism in Australia, given its history and the nature of the institution in which the production of it takes place. Docker’s book suggests that conflict shall continue to be the order of the day, but then again, anything is possible. In writing his book Docker has addressed one set of possibilities. As he says himself:

Overall, the argument of In a Critical Condition is that there is at the moment no clear dominance, no hegemony, of formalist criticism. And it is in this context, as an intervention in the debate, that I’ve written this book.

Comments powered by CComment