- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

If Australia during the last century was ‘no place for a nervous lady’, this collection of women’s writings edited by Lucy Frost establishes with simple eloquence that it certainly was no place for a nervous gentleman.

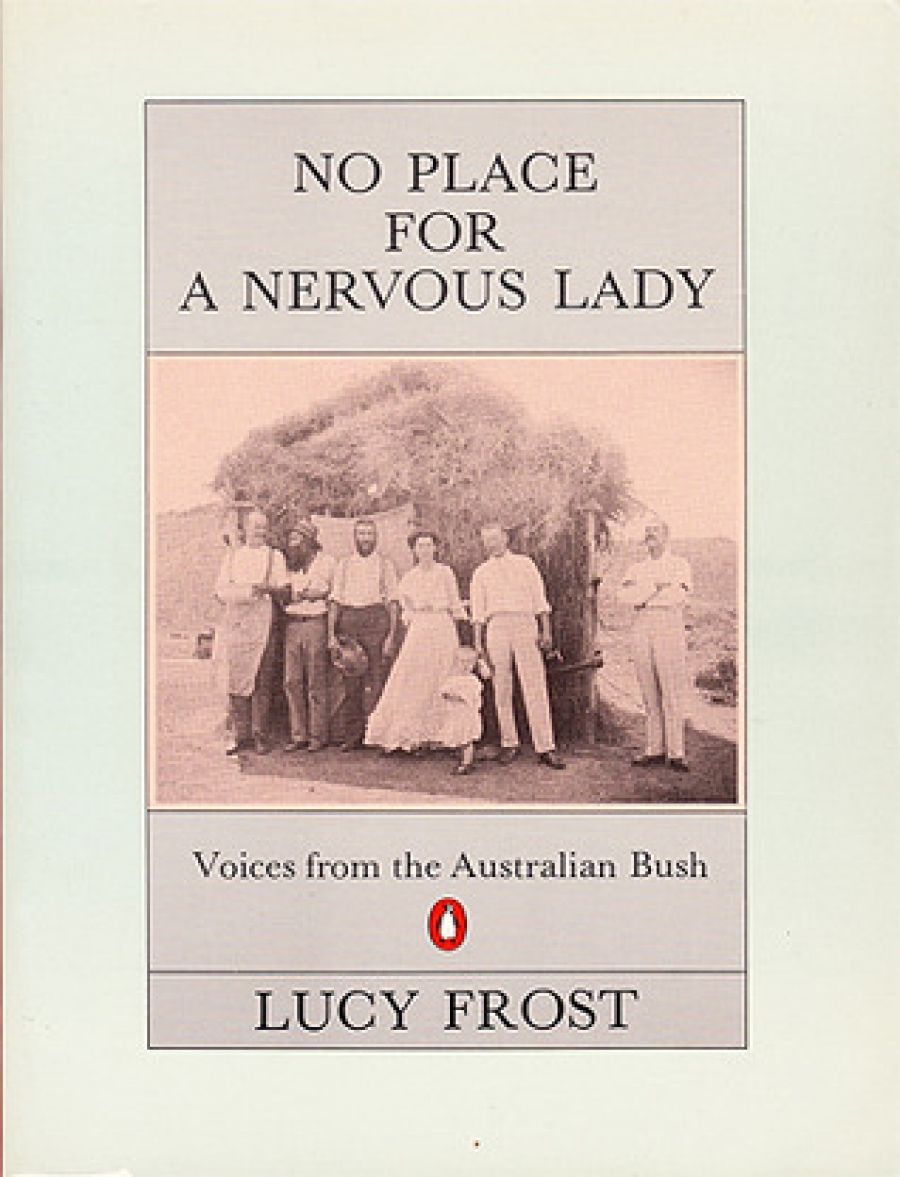

- Book 1 Title: No Place for a Nervous Lady

- Book 1 Subtitle: Voices from the Australian bush

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, $12.95, 284 pp

While the gentlemen take to drink and become no better than ‘the commonest persons’, the women battle not only the harshness of climate and the privations of the bush but also the exhaustion brought about by annual pregnancies. Pregnancies which deplete the body often without even the joy of a live birth. Penelope Selby, like the other Penelope, suffers from her husband’s wanderlust. Of the ‘lust’ which produces seven stillborn children, Penelope has nothing to say. However, although she ‘fervently’ hopes that she ‘shall have no more’ ‘as constant bloodletting ... will be my only safety and that of course must weaken me much’ she does have more and more and more still births.

Sarah Davenport, a much more uneducated woman than Penelope Selby, shares a resilience common to all these bush women. On the voyage out, after first experiencing a shipwreck and then the death of her child through an accidental scalding, Sarah Davenport records:

i had what was caled purmature labour and that babe was throne in the sea i was almost Dumb with grief i thought my tryals was heavey but i cryed unto God to help me for my chilldrens sake i had no one to comfort me in all my tryals for my husband seemed indifferend affter the ship wreck his kindness seemed to be all vanished and [another] spirit might have [taken] position of him.

Lucy Frost evaluates Sarah’s character and judges the husband. ‘This working-class wife had both [a cool head and a determined spirit], and it was just as well she did, because she was burdened not only with young children but also with a sickly and inept gentleman-husband.’ But from Sarah we hear no judgement: only a catalogue of one failure after another to secure a firm economic basis. The husband is the nervous gentleman who watches as his wife threatens to ‘brake’ a horse’s leg if the strong ‘vandamonians’ do not hold to their contract and take the family to Mount Alexander, another place where they hope to ‘beeter’ themselves.

From such an account it would appear that this publication is a feminist tract. And it is. But only in the sense that it seeks to release the ‘voices from the Australian bush’ which have been unrecognised as being part of Australia’s colonial heritage. Men’s voices have shaped the European experience, ‘Australia’s sons let us rejoice’, but the voices of women, like the voices of the local birds, have had to wait a long time to claim that theirs is also a song which has a harmony. Amidst the voices which come from diaries, letters and shaped reminiscences, the reader hears Lucy Frost’s warm, enthusiastic, and relaxed commentary. She has the capacity for a succinct summary which guides without lecturing and highlights without detracting from the freshness of the original documents. This is a rare quality in books which are academic. The researcher often is so overburdened by the weight of scholarship that any delight in the discovery of significant material is subsumed by the high-seriousness which this demands. Lucy Frost’s delight at presenting the material which has been imprisoned in the personal records of these women permeates not only her introduction and the commentaries at the beginning and end of the selections but also the notations to the photographs. ‘Why was this photograph taken? The man is not holding the axe like one used to woodchopping and the well-dressed woman sitting among the logs is surely part of the joke. Date and place unknown.’

There is a peculiar aesthetic which has shaped this work. It is Lucy Frost’s personality. She does not reject the personal voice and presses the migrant woman’s experience as part of her own experience.

As a migrant myself, I understand something about the peculiar psychological effects of growing into adulthood on one side of the globe and then taking up life in what must by definition be a strange environment tens of thousands of miles away from ‘home:

The publishers have caught in the technical production Frost’s personal, indeed idiosyncratic aesthetic. Form and format meld to create a tone and vision of last century’s historical period as produced by those women’s voices.

Although the research is thorough, and the notes and acknowledgements indicate this to be a scholarly work and not a popular compilation, the editor’s admission that she hopes that this collection ‘sits on that unseen borderline where history meets literary criticism’ may cause some ‘disciplinarians’ problems. A maverick American bucking at conventional wisdom in the Australian paddock may be more than the local brumbies can take. However, Lucy Frost has created for me an emotional landscape through the voices of the women from the bush which embodies a psychological fullness and complexity offered by few histories. For releasing these women from the archives, I thank Lucy.

Comments powered by CComment