- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

What is more common than the indicative mood, and what is more uncommon than the way Les Murray uses it? His Christian finger ‘scratches the other cheek’ (‘The Quality of Sprawl’) but more often points out tracks seen from the air, but invisible on the ground: a hibiscus becomes ‘the kleenex flower’ (‘A Retrospect of Humidity’); the shower an ‘inverse bidet,/ sleek vertical coruscating ghost of your inner river’ (‘Shower’); a north-coast punt ‘just a length of country road / afloat between two shores’ (‘Machine Portraits with Pendant Spaceman’). You see it in his use of the demonstrative pronoun – ‘this blast of trance’ (‘Shower’); the definite article – The man imposing spring here swats with his branch controlling it’(‘The Grassfire Stanzas’)’; the deictic use of ‘I’ and ‘we’ to get his readers looking in the same direction as he points out where we are and where we’ve come from – ‘So we’re sitting over our sick beloved engine / atop a great building of the double century / on the summit that exhilarates cars, the concrete vault on its thousands / of tonnes of height, far above the tidal turnaround’ (‘Fuel Stoppage on Gladesville Road Bridge in the Year 1980’).

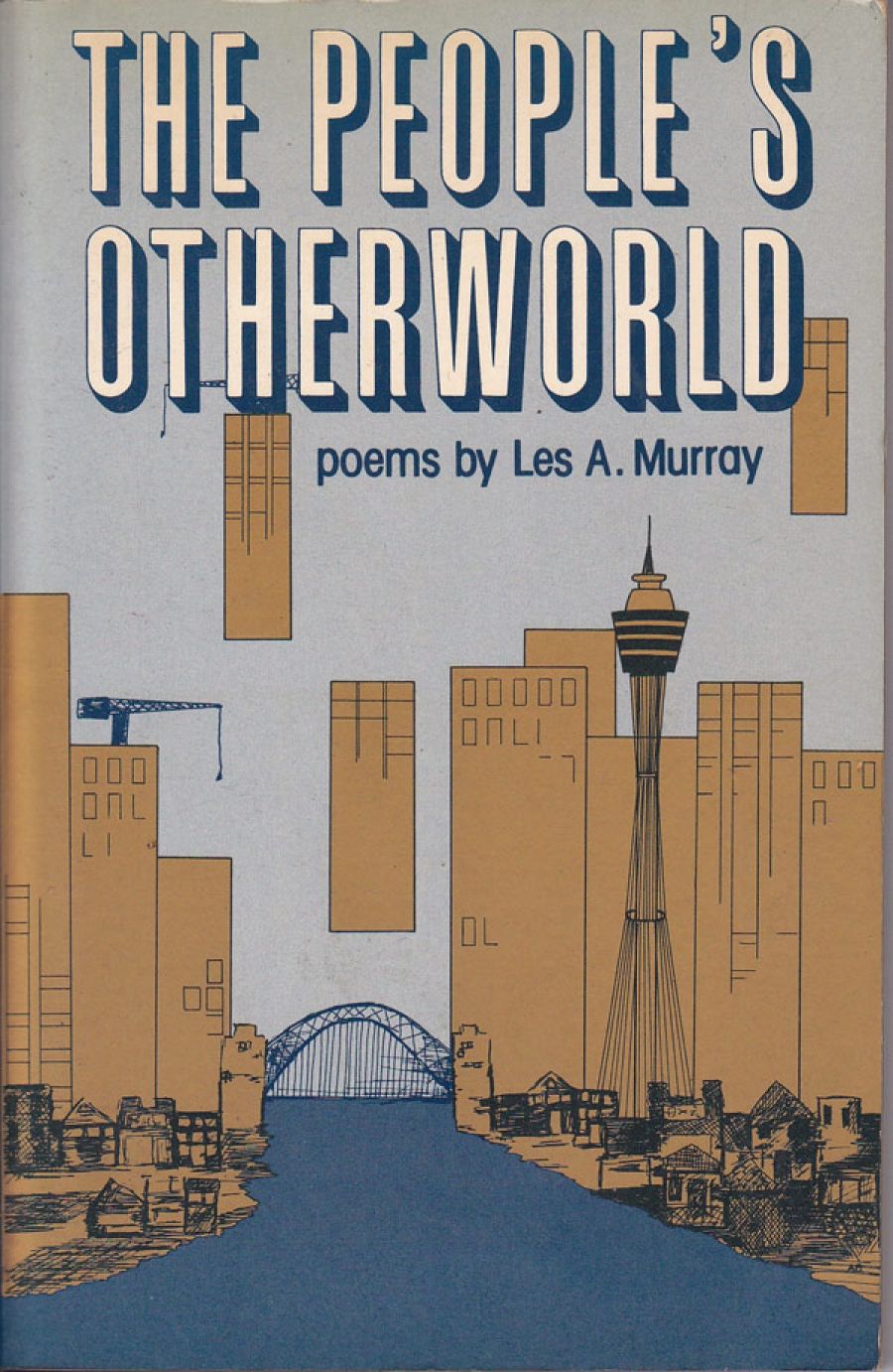

- Book 1 Title: The People’s Otherworld

- Book 1 Biblio: Angus & Robertson, $8.95 pb, 68 pp

This collection is a guided tour of the landscape of the Australian imagination by one of its ‘characters’ – he’s the driver of the bus everyone talks about at dinner – he knows all the local traditions, he’s watched that road go past for years, and he’s practised the stories, the telling phrase, the joke, the jollying along for years – often to himself. But he’s doing two things at once: he tells you what’s going past, and he’s also driving the bus to ‘the people’ otherworld’. He knows where he is going. He’s been there many times before. That certainly is what makes it worthwhile following the finger and listening to the dry expansive voice (just a bit like the country outside the cold of the air-conditioned window), even though sometimes when the commentary overwhelms you, you wish you were back in your own favourite chair with a cup of tea. But think of the views you would miss. ‘Where in Heaven?’ the driver asks; ‘Down these roads’ the guide tells us (‘Satis Passio’). And what a great poem that last one is (and it is the last in the collection).

According to Murray, most knowledge is poetry (how Harpur with his inheritance from Channing and the Americans would have agreed), and Art is that way of organising Nature to connect our pattern of perception with the pattern we sense in that Otherworld. Poetry is a general condition of the mind; it is games and the solutions of problems; it is technology. That north coast punt, the machine, bridges gaps and carries human thought with it over to the other kingdom which to the Christian is no end at all;

All machines in the end join God’s creation

growing bygone, given, changeless –

but a river ferry has its timeless mode

from the grinding reedy outset; it enforces contemplation.

We arrive. We traverse depth in thudding silence. We go on.(‘Machine Portraits with Pendant Spaceman’)

Many of Murray’s poems are about this synthesis of the dualities of Western thought: between reified technology and the numinous divine (Auden had a go at this too); between social order and abstract pattern (Aboriginal kinship systems and symmetrical transforms do this as well); between subject and object which disappear in the dream, and the dream is not Plato’s or Freud’s, but an older one of prophecies and underworlds.

The spirit of fun and games is abroad in these poems. Sometimes it gets out of hand. One example in an intriguing poem throws the whole thing out of kilter with a flippant pun I would have been proud of in the pub talking about the link between dreams and the real world, but in this context, no:

moor things in Heaven and earth

then, Ratio, anyhow, you can

because dream’s the looseleaf book,

not of fiction, but of raw Pretend,(‘The Dialect of Dreams’)

But in ‘Sprawl’ and ‘Homage to the Launching Place’ the wit and ebullience are marvellous.

There’s a sense of restlessness in this period of Murray’s poetry, the kind of restlessness that led him to play at length with the sonnet in The Boys Who Stole the Funeral. Here you can see it in the sound play of ‘The Mouthless Image of God in the Hunter-Colo Mountains’ which is a bravura piece of internal rhymes, assonance, consonance, onomatopoeia which would warm the heart of any teacher of school poetry, but it reads to me like the equivalent of those extraordinary Venetian bands of a 100 mandolins plucking the heart out of some work originally written for a small consort of strings. But that is an extreme example, and anyway there are parts of it I can warm to. Set by this poem in the collection is the beautiful music of ‘The Chimes of Neigeschah’ which carries on in Murray-style the successes of John Shaw Neilson’s and Kenneth Slessor’s development of sensuous prosody. It is seen again in the perfectly controlled stanzas, but all overflowing with dense images of Murray’s memories of wartime Newcastle, in ‘The Smell of Coal Smoke’. Both these poems are satisfying examples of the poet’s great powers of integrating his highly tuned visual sense with the amplitude of his language.

A new note in the book is a more personal tone. We are used to his tone of spokesman, guide, seer, but there is not much of other side of the ‘poet’s two-fold life’ which Kendall cursed personal suffering and anguish. But at the heart of this volume are three very moving poems to the memory of his mother who died when the poet was twelve. ‘I’ in these poems is not the oracular personal pronoun of the expansive poems, but the small space of a little boy and the hurt adult processing the memories of his mother’s death due to professional neglect after a miscarriage.

I did not know back then

Not for many years what it was,

after me, she could not carry.(‘Weights’)

But you don’t remember.

A doorstep of numbed creek water the colour of tears

but you don’t remember.

I will have to die before you remember.(‘Midsummer Ice’)

I am older than my mother. Cold steel hurried me from her womb.

I haven’t got a star.(‘The Steel’)

And so you come to the end of the book where three poems on poetry bring together Murray’s ideas about the imagination, art, and the divine. Often our poets write to programs when they write about these subjects, or deal with them obliquely with symbols, or use images without calligraphy to suggest them; Murray makes them live with his splendid language and his rich visual imagination. The standing wave of eternal flux which A.D. Hope used in his Sackville Digby Epistle was a metaphysical symbol, for Murray it lives in the physical world and yet is still divine, and his language gives it life (‘Bent Water in the Tasmanian Highlands’). His poetry is like that water, fluid but permanent:

Art’s best is a standing miracle

at an uncrossable slight distance,

an anomaly, finite but inexhaustible,

unaltered after analysis

as an ancient face.(‘Satis Passio’)

Comments powered by CComment