- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

On Hydra last year an old grocer wound up his reminiscences of George Johnston and Charmian Clift with a tolerant grin. ‘They both drank a lot,’ he told me. ‘They had to – yia na katevei i skepsi.’ For the thought to be let down: he used the same verb as for a cow letting her milk flow. ‘They drank a lot; they wrote a lot of books.’ He shrugged.

- Book 1 Title: Strong-man from Piraeus and other stories

- Book 1 Biblio: Thomas Nelson, $16.96 pb, 192 pp

- Book 2 Title: The World of Charmian Clift

- Book 2 Biblio: Collins, $14.95 pb, 255 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/1_Meta/Socials/JanFeb2020/nb_0567.jpg

Part of the fascination of it is that they both told so much, and their versions differ so often, and sometimes clash. Clift’s always leaned closer to the romantic legend, blithe where his is dour: an anguished disillusionment pervades the trilogy. Again and again you come across a passage, in her books or his, that throws new light on passages elsewhere, so the multiple resonances, perspectives, layers of irony are set up. The more that Johnston’s Meredith exposes, the more mysterious gaps and hollows appear. Well, the more you know of someone, the more you want to know: The World of Chairman Clift, and Strong-man from Piraeus especially (being new), will have many eager readers.

The World of Charmian Clift is a dense, handsome volume with a leonine tawny head of her on the cover. Having read most of these newspapers pieces (eagerly) as they appeared, and again when the original Ure Smith edition came out in 1970, I thought I’d just dip into them this time. Pieces on travels, memories, people, experiences, ideas, all as chatty and seemingly intimate as letters, they have lost none of their savour: her maturity, candour, and good humour shine as much in them as in Mermaid Singing and Peel Me a Lotus. I ended up reading them all again from cover to cover.

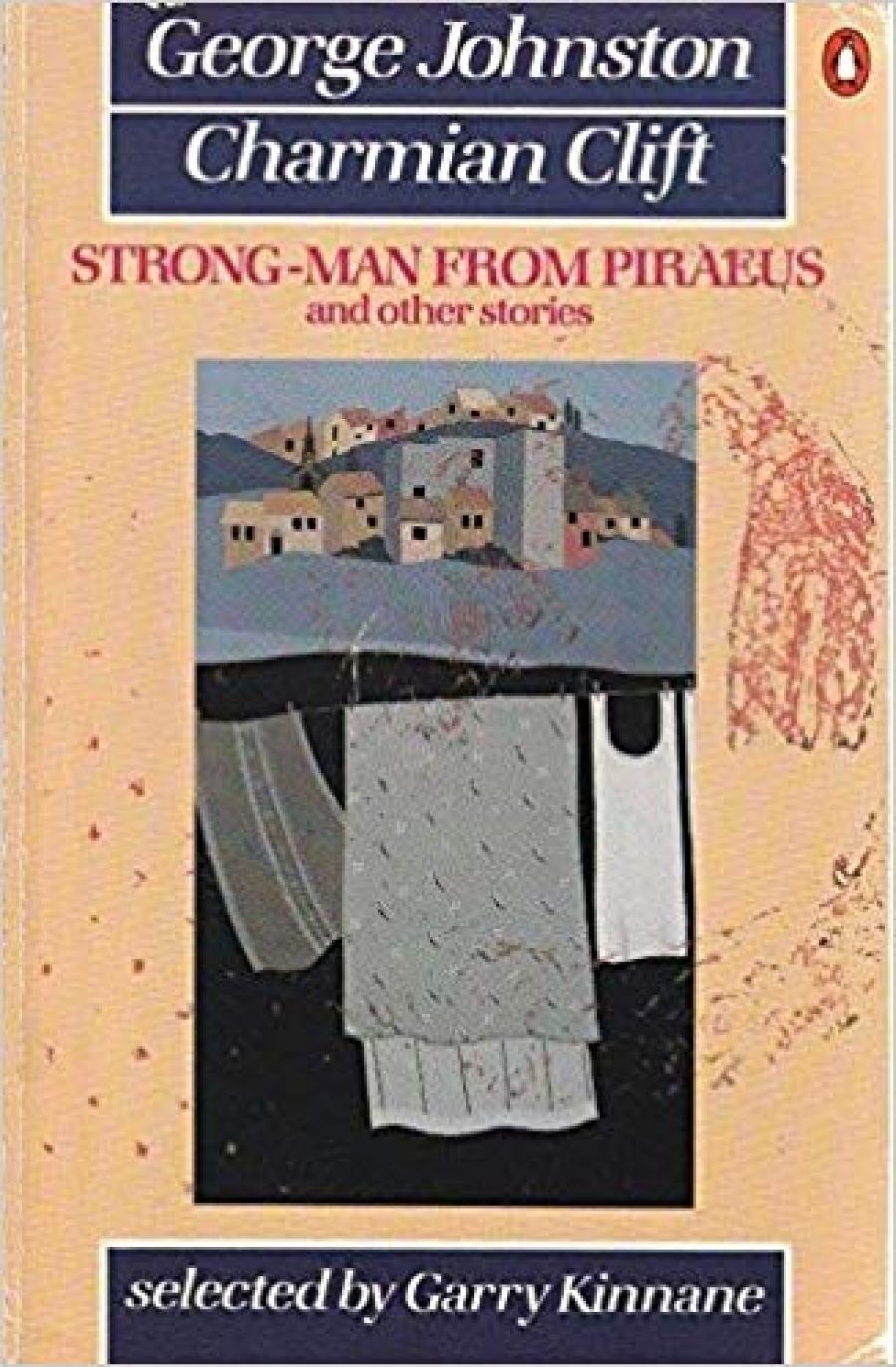

Strong-man from Piraeus, another good-looking book – a watercolour by Elizabeth Honey on the front, a smiling family photo on the back cover – is a collection of (mostly) unpublished stories from the fifties or earlier, four by Clift and seven by Johnston. They offer a taste – foretaste or aftertaste, depending – of the later work. They vary hugely in quality, the Clift ones especially: mawkish ineptitude in ‘Even the Thrush Has Wings’ (but she was only twenty-five), to intensity, incandescence, in her ‘Wild Emperor’. Garry Kinnane, who selected the stories, notes in his excellent introduction this story’s ‘Lawrentian vibrancy and decisiveness’. But ‘The Small Animus’, hardly even a story, belongs in Mermaid Singing, where its sugar coating doesn’t set the teeth on edge. ‘Three Old Men of Lerici’ has good moments only. The three old men appear almost word for word in Clean Straw for Nothing (so who borrowed?): here their music brings Ursula, a stereotyped rich bitch who has hurt her young lover, a moment of insight that oddly parallels David Meredith’s. The last sentence reaches a tired resolution: ‘Freiburg’s maudlin tears had soaked through her nightgown. She could feel them spreading hot and wet across her bosom, as if her heart had burst.’

Most of the stories by Johnston are both slight and overwritten, their characters wooden. Some aimed at high drama-’The Dying Day of Francis Bainsbridge’, ‘Requiem Mass’ – career into bathos and melodrama. Attempts at humour, as often as not, fall heavily. ‘Astypalaian Knife’ and ‘Strong-man from Piraeus’ itself are magazine pap, thin and laborious; ‘Vale, Pollini!’ – a tilt at the pseudo-intellectuals infesting Hydra – is a good joke that soon goes sour. The humour of it snarls and jeers, in interesting contrast to the frank and fond and joyous fun that Clift could poke at the same nuisances. His ‘Sponge Boat’, though, is a fine story, heavy with antagonisms that brew and climax in a killing, relapsing then into a sullen resignation. As for ‘The Verdict’, in which David Meredith wanders in despair round Athens until he can see the doctor from whom he expects a death sentence: this story went almost intact into Clean Straw for Nothing. The stories provide more echoes and cross-references to tease the mind. In a piece in The World of Charmian Clift, she has met in Sydney a taxi driver from the Tyrolean village in her ‘Wild Emperor’. In another piece, she mentions that she always cries at a particular passage of Mozart’s Requiem; the heroine, Erica, in Johnston’s ‘Requiem Mass’ always does too-the mystery of her crying is at the crux of the story. In Clean Straw for Nothing, Meredith is tortured by the knowledge that Cressida hears a music that he can’t. Moreover, in Clift’s ‘Three Old Men of Lerici’, it’s Ursula’s realisation that her lover hears the secret music (‘But then ... Freiburg hears it all the time’) that brings about her change of heart. Ursula was destroying Freiburg; Erica’s husband does destroy her; Meredith dreads all along that Cressida will destroy him; his friend warned him that they would destroy each other.

Mutual destruction is at the heart of the legend of Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald as well. In his introduction Garry Kinnane compares the Johnston legend to the Fitzgerald one, remarking: ‘except that Zelda wasn’t a writer’. Well, Zelda believed she was. Clift, anyway, had proved that she was. Johnston’s introduction to The World of Charmian Clift leaves us in no doubt of his admiration, his pride in her work. They even collaborated. Yet Cressida in the trilogy – the wife, the mother, the adulteress – isn’t a writer. So why, when he laid bare so much, did Johnston/ Meredith draw the line there?

Read these books, but expect them to solve no mysteries. ‘Intriguing and disturbing’ their authors remain.

Comments powered by CComment