- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Opera

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

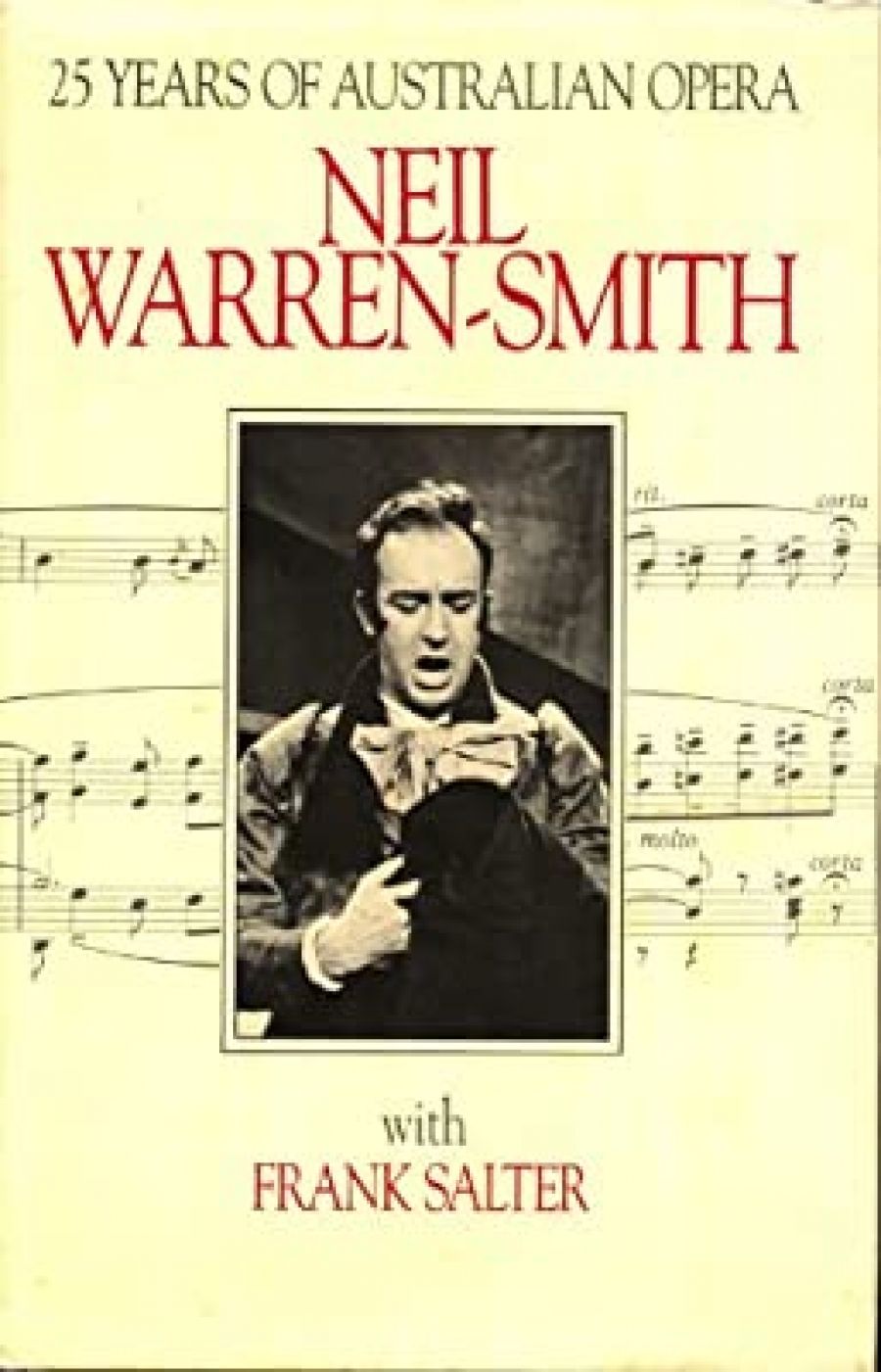

That Neil Warren-Smith was a magnificent singer and actor I knew from having seen him in many Trust and Australian Opera seasons, including the very first in 1956. But his proneness to appear as czars, monks, ancient sages, field marshals and similar dignified personages had concealed from me that he was also a magnificent larrikin. This is a very welcome bonus of what is, sadly, a posthumous autobiography, talked with unblushing frankness down a tape recorder and presented with what seems to have been a minimum of intervention by Frank Salter.

- Book 1 Title: 25 Years of Australian Opera

- Book 1 Biblio: Oxford University Press, 180 pp, $22.50 hb

That an apprentice butcher should have graduated as a master basso is not in the least strange once we understand that the combination of a Voice and an Ear generates a momentum of its own quite independent of the intentions of their possessor. The process began when his mother interrupted an imitation of the Ink Spots (all of them at once) on the front verandah with the fateful remark ‘I think you’ve got quite a nice voice and I’d like you to learn’. Next came lessons from a pin-striped gentleman with a mania for scales, interminable practice of the said scales – and virtually nothing else – with a piano-playing family friend, and his first essays at the talent quests and eisteddfods which were then a young singer’s main reason for existence. All this is hilariously presented as a budding bodgie’s reluctant progress to what he then saw as the totally uninviting pinnacles of high art.

Things improved when he was told by his teacher to audition for the choir of Melbourne’s Anglican cathedral. Expecting to find his follow-choristers ‘soaked in sanctimony’ he was delighted to find he was among ‘some of the hardest drinkers and greatest sports I’d ever met’. It was here that he discovered for the first time that singing – real singing – was fun. Having survived the horrors of his first Leporello, mugged-up at short notice, and shared the esprit de corps of the Trust’s Mozart tour, he realised that opera was fun too and devoted the rest of his life to making it fun for other people as well.

The latter part of the book will be of greatest interest to those who remember the roles, productions, and performers he describes, sometimes con amore and sometimes with devastating but wholly unmalicious humour. His artistic priorities are unashamedly vocal. Conductors are appraised in terms of what they give to singers (by which he does not mean coddling them) and producers by whether they allow singers to get on with their job without having to worry about falling over bits of the set. He regrets that in his one attempt at the title-role in Don Giovanni he was undermined by Jim Sharman ‘s notorious ‘chessboard’ production, though my own recollection is that Warren-Smith and Mozart, always a formidable combination, more than held their own against the inadequacies of the staging.

Another role he disliked was Bottom in the Australian Opera’s Midsummer Night’s Dream – to my mind one of their two or three best productions ever and his own finest comic performance. Still, his intermittent expressions of utter vacuity, which I now realise were due to furious counting, perfectly fitted the character. Let us hope that when he sings Bottom in Elysium all the counting is done by Attendant Genii and that he can enjoy his performance in the true larrikin spirit by having fun as well as giving it.

Comments powered by CComment