- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The idea of the sequel probably goes back to the earliest cave drawings in the bowels of the oldest hills. ‘What happened next?’ was surely .among the first words babies ever gurgled as parents grunted bedtime stories around ancient camp-fires. It is not given to the armchair anthropologist to know whether· ‘What happened before that?’ is quite so fundamental, but I suspect not – otherwise, stories would begin with an end at least as often as they do with a beginning.

Sure, we ask questions like ‘Where Did I Come From?’ and ‘Who Made the World?’. But let’s face it, who’d want to sit down with a good old Mills and Boon romance if they knew the heroine was going to get the fella with the curly lip on the first page and then have to go back and pretend to hate him for the rest of the book? A whodunit that got solve in the first chapter would need to have a lot else going for it. The question is: If you had read and enjoyed Ruth Park’s The Harp in the South and its sequel, Poor Man’s Orange, would you really want to go back and read Missus, the first novel in the series, especially if you knew it was written almost four decades later?

Not that a lot of-successful writers haven’t begun where they jolly well pleased, learning to travel back and forth at will and with ease within a narrative, particularly in our life-times, but writers are always turning tables on heads. Nothing new would ever get written if they weren’t, and even in the more serious echelons of literature, where this style of thing began, the born story-teller knows that characters have got to be born before they can get married and die, that the human mind, whether it be seeking escape or inspiration is geared to the idea of progression, call it growth if you must. The fragmentation of the traditional narrative has been one of the biggest jobs writers have performed for literature in the twentieth century, but at the enormous cost of a steadily shrinking and increasingly elitist readership. Where the popular novel does ape its betters, you can be pretty sure that the girl will still have to wait till the last page or two to get the fella, no matter how nimbly the narrator manipulates the time-scale.

Alright, granted, there is a lot of leeway for the writer who chooses to ignore the popular market and the demand for undemanding literature. But are they really the same thing? This question has waxed and waned, no doubt, since the first words were ever woven into stories. For Australian literature it has been the leaven in the loaf as far as the great social realist/metaphysical etc. debate has been concerned.

Ruth Park is not the sort of novelist who mucks around with the timehonoured assumptions about form and craft in fiction, nevertheless she can be a very serious writer. The easy label is probably ‘popular social realist’ – a little tight across the shoulders, perhaps, but mostly it fits. But Park is one of those writers who simply doesn’t allow of any neatly interlocking arrangement between popular and undemanding.

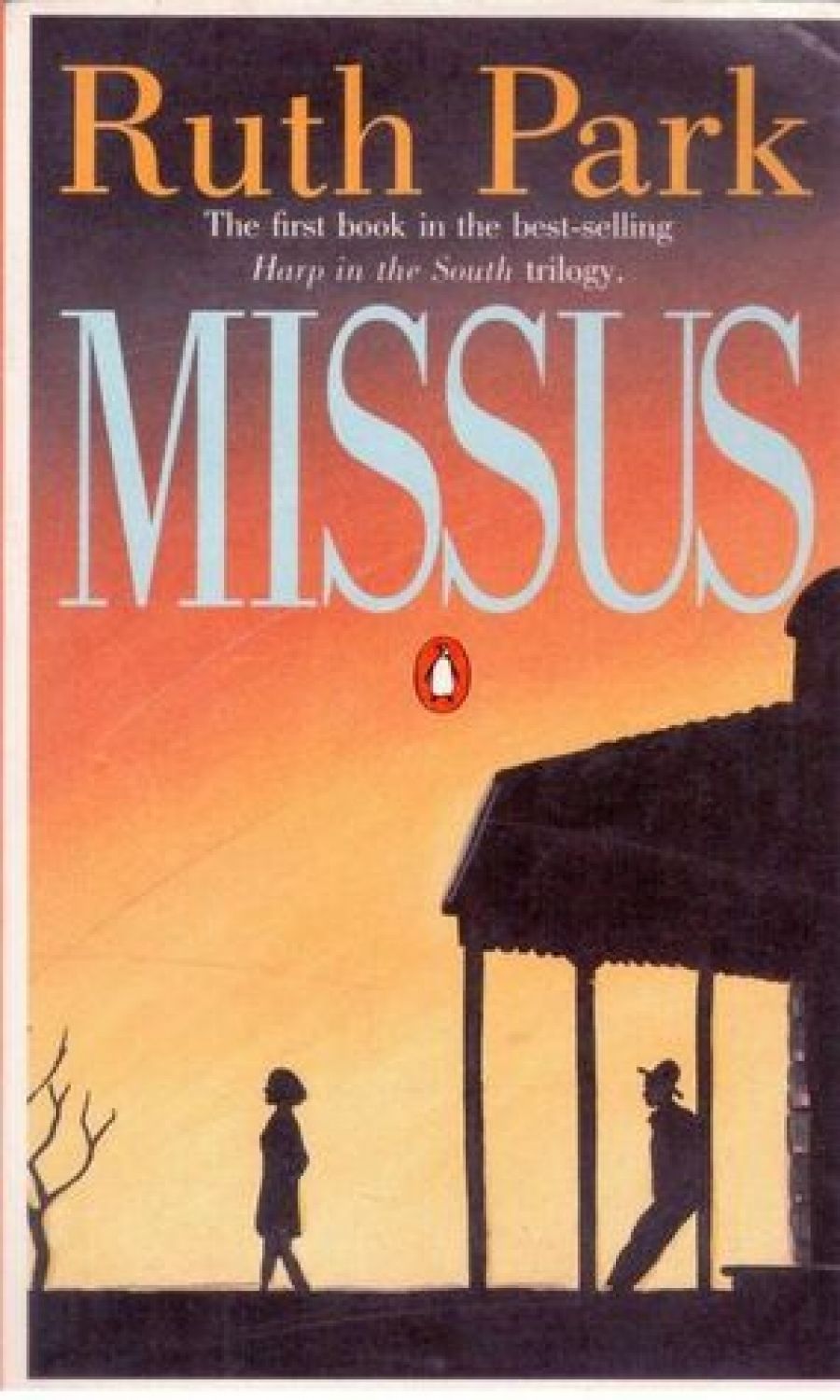

Popular, she certainly is, and by any professional writer’s standards, successful. Her new novel, Missus has been purchased by Thomas Nelson (Australia) for a ‘record sum’, which would be enough evidence in itself for some reviewers and critics to dump it in the bestseller bin and write it off accordingly. It is being released in hardback in what the blurb refers to as a ‘big’ edition. Her novels The Harp in the South and its sequel, Poor Man’s Orange have never been out of print since they were published in 1948 and 1949 respectively and The Harp, which has so far sold 250,000 copies will soon be released as a mini-series. As some measure of her success overseas, suffice it to say that her third novel, The Witch’s Thorn sold 400,000 copies in the U.S. and that she has been translated into many languages. She won the Sydney Morning Herald award of 2,000 pounds in 1947 for The Harp (ahead of Jon Cleary) and her finest novel, Swords and Crowns and Rings won the Miles Franklin Award in 1977. She has worked as a journalist, written for radio and T.V. and won the Australian Children’s Book of the Year Award in 1981 for Playing Beatie Bow.

Now almost forty years after The Harp was first serialised in the Sydney Morning Herald, the tale of Hughie Darcy and his family has become a trilogy. No doubt we must thank that feverish brains trust which coins terms in the U.S. and exports them to the colonies for the term ‘prequel’ which is being used to describe this late return to that rich Harp territory. The surprising thing is not that Park should want to dig over such fertile ground again but that she should have chosen to write a prequel, surely a dicier proposition for publisher and writer alike, when she might have written another sequel. Why, as both a commercial and popular success, would Park choose to flout the rules of common or garden publishing sense?

Ruth Park puts it down to a simple response to suggestions from her readers, and is obviously not unaware of the difficulties involved.

Since The Harp in the South and Poor Man’s Orange first appeared, many readers have written to me asking what happened to the characters after the story finished. Often they enclosed pretty spaced-out suggestions of their own. Others have asked what the characters were like when young. Old chaps have boasted that they knew Grandma – a real whizzer – or that they lived in the Surry Hills house the Darcys rented. Astonishingly, one elderly gentleman really had lived in that house. It was a real one, though I’d described only bits and scraps of it.

In the end I suppose I became curious myself. It’s fairly easy for a people-watching writer to begin with a youthful character and work with him until he’s tottery, for the seeds of maturity and beyond are present in every youngster. ‘In my beginning is my end,’ so to speak. But to do this in reverse is backbreaking. The branches and even flowers of the man’s life are right before you, but what do the roots look like?

For those who are not among the hundreds of thousands of Aussies who have laughed and cried with (or about) the Darcys at Number Twelve-and-a-Half Plymouth Street, Surry Hills, a quick resume. With the possible exception of Swords and Crowns and Rings, Ruth Park is not a dab hand with a plot, but more a writer of incident, character and situation. Surry Hills in the forties is full of creaking, leaky little houses, foul backyards, prostitutes, little crims, bed bugs and Irish Catholicism. In The Harp, Hughie Darcy (Dad) is an alcoholic who somehow manages to keep his job, but not his family in any degree of comfort. He is middle-aged, but not yet desperately so. Mumma, his wife, has long since lost both her Christian and her family names, but not all of her individuality. She dotes on Hughie and their two daughters. Roie is the gentle one who has most of the awful things happen to her in this book, but gets married at the end and dies in childbirth in Poor Man’s Orange. Dolour, my favourite, is the spirited one who might, just might, one day transcend Surry Hills and all that it stands for. She ends up with her sister’s widowed husband. Their young brother, Thady, has disappeared years ago without trace – just picked up off the street and never seen again.

Then there are the lodgers. Miss Shiely whose idiot son, Johnny, gets squashed by a bus in the second chapter and Patrick Diamond, the Orangeman and Hughie’s friend, except on St. Patrick’s Day when anything can happen. There is Grandma, razor-sharp of tongue and distrustful of Hughie for her daughter’s sake (and quite rightly so); Lick Jimmy, the Chinese grocer, Delie Stock, the ageing, filthy rich prostitute with the heart of gold who would also murder you if she had a reason to. The tapestry is rich in characters drawn from Park’s experience of life in Surry Hills in the forties.

Missus goes right back to Hughie and Mumma (who is now Margaret) as children, but focuses mainly on the long and drawn out battle their relationship is until they finally marry at the end of the book. The pity of it all is that Missus is really better written than either of its predecessors, but somehow less satisfying. It is a tale, basically, of selfishness. There is the young Hugh – a great hit with the girls, irresponsible, often drunk; his crippled younger brother, Jer, who is a great one with the songs and the stories, but an inveterate liar and not above the most appalling interference in other people’s lives. Jer wants Hugh to marry Margaret, because he calculates that Margaret’s kind heart would insist on her offering him a home. But Hugh, already engaged to Margaret, falls in love with someone a lot more exciting who also falls in love with him. But what with Jer’s sneaky interference and Margaret’s wanting Hugh at any price, they end up married. Margaret is now Hugh’s ‘missus’ and will never sleep in a decent bed again.

My disappointment really stems from the fact that the roots are there, as Parle herself says, in the other two novels, and this one lacks any substantial surprises. In an article which appeared in the National Times last year, Park herself puts it very well: ‘I believe that writing – and indeed any art, as well as the ideational stage of many sciences – is basically an outcropping from areas of the mind we’re just starting to chart. I don’t know what these areas are: I only know they’re good, and that’s where creativity lies.’

If Missus fails on the literary level, it is precisely because it makes no effective attempt at any of that territory we’re ‘just starting to chart’. Readers coming to Missus from the more recent Swords and Crowns and Rings will be particularly disappointed for this reason. To put it in a more commercial light, what this novel really lacks is any possibility of a happy ending. I mean ‘happy ending’ in its widest sense, and in the way I suspect Ruth Park usually means it – a promise of hope and life, some kind of future – and I rather think this is what her readers will be wanting.

Besides, it wasn’t just the character of Hugh Darcy that sold The Harp. It was also, at least in the beginning, a semi-shocked response by Australians to the facts of Surry Hills life as Park described it. The Sydney Morning Herald published column after column of response from the public as the novel was being serialised. Some ticked her off as a New Zealander born and bred who had the temerity to come to Australia and spread filthy lies about the place. Others were thrilled that here was a writer who could tackle everything from a backyard abortion to bed bugs and tell it just as it was. In February, 194 7 she wrote in the Australasian Book News: ‘Lots of people came down on me like a ton of bricks for writing about slums. They accused me of depicting the worst side of Australia, apparently in order to discourage immigration or something … The Harp wasn’t fiction, but a literal report of what I saw.’ She hasn’t got the advantage of that background in Missus, which is set in the New South Wales countryside.

According to The Drums Go Bang, the autobiography she wrote with her husband, the late Darcy Niland, when they set out to earn their income from freelance writing in Australia in the forties, the only person who was getting away with it was Ion Idriess. But Park and Niland did get away with it, particularly Ruth Park who has become a household name in Australia, and if for no other reason, Missus will sell. But without all those Surry Hills ‘characters’, will it sell well enough to dispose of a ‘big’ printing of the hardback edition? Her publishers are certainly hoping so and doing their darndest to see that it does. Rarely does a book hit a reviewer’s desk bolstered up by such a hefty wad of background on the writer – a complete (and impressive) list of her books, prizes etc. and a specially prepared statement from the author about just why she wrote this particular book. Just as well, though, because Ruth Park and her work have been seriously overlooked by the more academic end of the book business in Australia. A riffle through the annual bibliography of Australian Literary Studies yields only two references, both in the one year. Even the Miles Franklin Award which she won for Swords and Crowns and Rings in 1977 doesn’t seem to have kindled much serious interest in her work.

A quick and obvious comparison with Frank Hardy is a bit of an eyeopener. Hardy, who, to my mind hasn’t written anything as good as Swords and Crowns and Rings, and who, at his worst has been no better than Park at hers, has received a quite respectable degree of critical attention. It mayn’t have been all to his liking but it has been there. Yet Hardy has been no less a ‘commercial’ and ‘popular’ writer and probably no more of a political one than Park has. It would be a shame if no-one sat down to put serious critical pen to paper during Ruth Park’s lifetime.

Comments powered by CComment