- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Special Women

- Article Subtitle: And superb storytelling

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

What a pleasure to be reviewing Kate Grenville’s collection of stories and her novel!

First, Bearded Ladies: The stories are a delight. Ranging with ease over four continents, they portray women in a variety of relationships – girls brought face-to-face with a sexual world, women coping with men, without men, women learning to be. The writing is witty, satirical, compassionate, clear as a rock pool and as full of treasures.

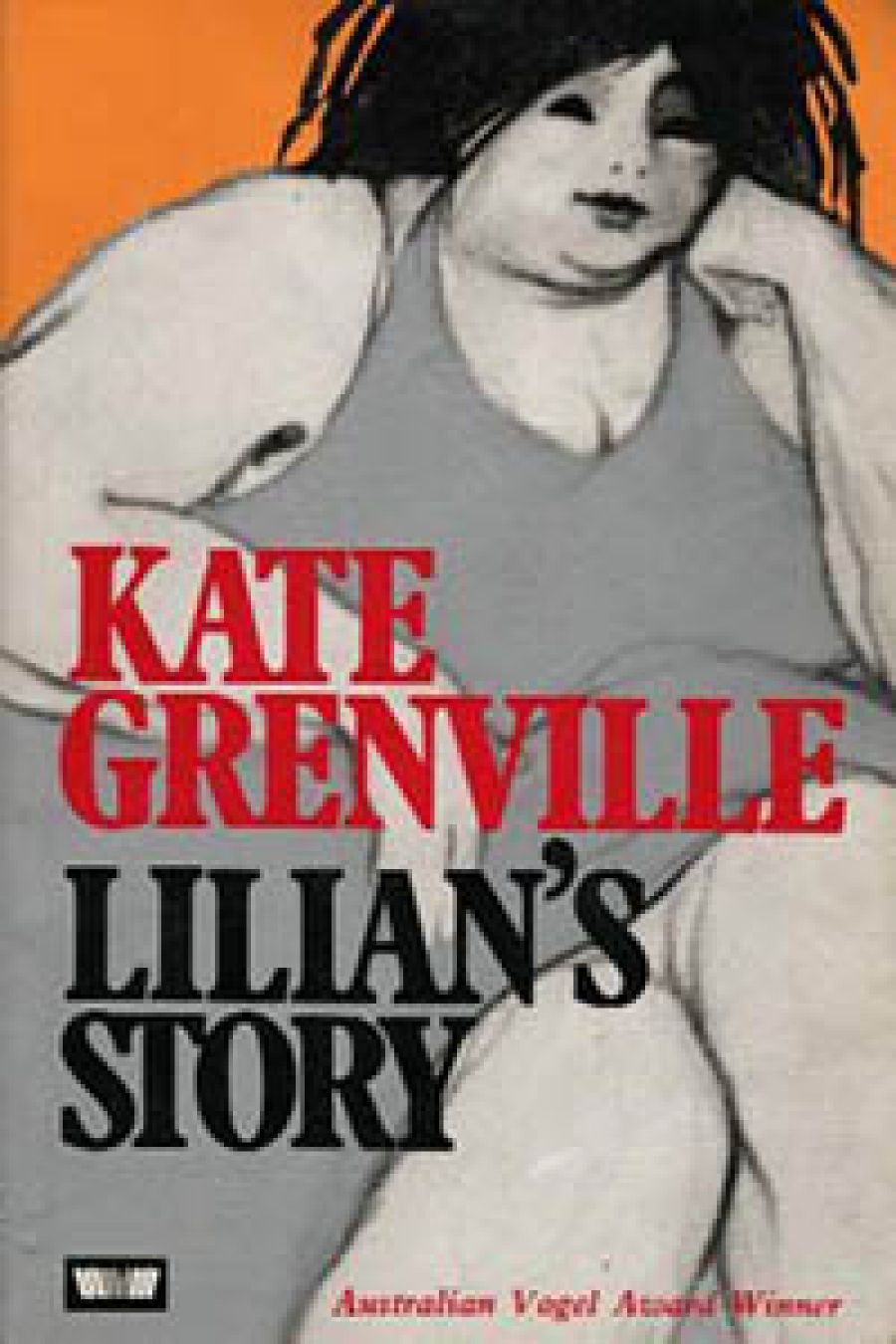

- Book 1 Title: Lilian’s Story

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, 212pp, $14.95

- Book 2 Title: Bearded Ladies

- Book 2 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, 176pp, $8.95 pb

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Digitising_2021/Archives_and_Online_Exclusives/breaded ladies.jpg

The very first page is a fine example of Grenville’s method. The placing of the adjective in the opening sentence brings it to immediate life: ‘The banana-shaped tourists lie in chairs by the swimming pool …’ The tourists are having drinks. ‘The daring ones have ice.’ (That’s about the extent of their daring.) Here in the hotel grounds ‘the sun has been domesticated ... Madras is far away as a travel book.’ This satirical picture of foreign travel serves to introduce the theme of the story: the attempted domestication of the central character, a young woman called Sandy travelling alone through India in baggy shirt and trousers.

In this same story, a group of Indian children gather around Sandy. ‘On the fringes of the silent group the girls stand, curious ...’ These girls, minor characters in the story, nevertheless epitomize the women in Bearded Ladies. Whether they are full of vitality like Sandy, or listless like the Indian girls, the women in Bearded Ladies are always on the fringe of things, outsiders. The closest of relationships can be as strange a place as a foreign country. Each person is just a bit freakish, either to herself or to others. Hence the title of the collection.

One story, ‘Blast Off, is presented as dramatic monologue:

New book blah

when I was in blah I was talking to

Name Name

and he said blah ha ha.

Original, naughty, satirical, it’s very funny. Sometimes Grenville will make you draw up sharp in the middle of a laugh, as in the comic story ‘Junction’ where the theme of loneliness isn’t funny at all. The junction of the title is that exquisite place where comedy and pathos meet. (This is the only story, incidentally, in which the central character is a male.)

Narrators whose observations satirize others are often satirized themselves. Irony adds another dimension to the stories. In ‘No Such Thing as a Free Lunch’ the narrator feels a cut above not only her garrulous male companion but also the beautifully-manicured woman at the next table whose every gesture conveys acquiescence to the dominant male. The narrator’s superiority – and the reader’s – is jolted when the woman turns to her and winks, a wink that conveys the sisterhood of the two bored women listening to men.

A consistent theme runs through both the short stories and the novel. It is the attempted destruction of the non-conformist. If someone else isn’t trying to change you, then you’re pulled two ways at once trying to change yourself. The tomboy Sandra in ‘The Test Is, If They Drown’ is proud to compete with boys on their own terms. She can spit. She has a gang of her own. But leadership, she discovers, means falling into line. To retain her reputation for individuality she is forced to attack the individuality of someone else. There is a very similar episode in the novel.

Lilian’s Story well deserves the esteemed Australian/Vogel Literary Award for 1984. Lilian Singer resembles Bea Miles, Sydney eccentric of the first order, but it isn’t necessary to know anything about Bea Miles to appreciate Kate Grenville’s marvellous creation.

Portents of Shakespearian magnitude occur the night Lilian is born. They, are appropriate to the scope of Grenville’s undertaking. The infant is born with a caul, supposedly lucky, and a preservative against drowning. Certainly later, when her father throws her cherished copy of Shakespeare into the river, this symbolic attempt to drown her fails because she has the text safe in her head. ‘William’ becomes her staunch and life-long friend. I think he would have appreciated her.

Lilian’s family is Victorian in the worst sense. Mother, ‘a woman of pale colours’, is totally unprepared for life – hers or anyone else’s. Father does something terribly important behind the closed door of his study, where dust lies ‘in a nervous way’.

Father’s name is Albion, which will send readers seeking resonances to chase him up in Blake. Blake’s Albion is the Father of all mankind: Albion Singer, ‘straddling the world with his muscular legs’, is the most influential person in Lilian’s world. Jealous, Blake’s Albion hides his daughter from her intended spouse: Grenville’s Albion does his best to prevent Lilian from embracing life. Emotion overwhelms Reason: that too, though in the novel Albion’s Reason extends not much further than collecting Facts (with a capital F) and spouting them over dinner.

Perhaps Blake’s lines closest to Lilian are those which open ‘Visions of the Daughters of Albion’. Lilian is the victim of Albion’s ‘terrible thunders’. Only wimpy women like Mother can exist in Albion’s world. He beats Lilian regularly – on her bare behind – climaxing just as she is on the brink of independence and happiness, in a final horrendous assault.

Throughout her childhood Lilian, a loving child, has sought to please this dreadful man, and at the same time to be her own self, inquiring, tomboyish, courageous, exuberant. There are some wonderfully comic scenes where Lilian is produced to perform at afternoon tea. ‘A lady does not hurtle, Lilian dear,’ Mother tells her. This conflict within herself leads Lilian, seeking love herself, to betray people she loves – her brother John to whom she has been fiercely loyal (the brother-sister relationship is sensitively portrayed), her pathologically shy schoolfriend, the strange old neighbour who befriends her.

Of this woman, Mother tells Lilian ‘It is hard for jilted women. Oddness is to be expected.’ Well, Mother has been jilted by life, and so, thanks to Father, has Lilian – almost. She is forced to make her own life, create herself. And odd she certainly becomes.

Her eccentricity in the face of normality is superbly conveyed. It is her point of view we see things from:

Lil jumps into a taxi for one of her free rides. (Lucky passengers get a recitation of William.) ‘The man in the back seat ... was one of those who say nothing rather than say anything foolish.’ The taxi driver, however, ‘shouted and pushed at my shoulder until the lights changed and he was forced to drive on, but continued slapping at my leg until all around us cars were honking at his erratic course from lane to lane. Keep your eyes on the road, I told him, and turned to the bogus man in the back seat, who was staring out of his window as if Market Street was interesting. This man is driving badly, I told him ...’ When the passenger refuses to respond Lil tells him ‘Timidity is no good to anyone … You are a success, I said ... But you are hollow ... I am disappointed in you, I told him as I opened my door and got out, ignoring the driver, who was still shouting, and now trying to hold me.’

Which of the three is the craziest?

Short story writing has trained Grenville in the quick sketch, the sharp outline. ‘Now I was fat ... I was the one called to jump up and down 1f anyone needed a stick snapped.’ There is a rich array of minor characters: Rick the foreverout-of-reach boy Lilian has a crush

on; her friends during the happy time at University; kindly alcoholic Aunt Kitty who comes to her rescue; Jewel who thinks she is pregnant with God.

As in the short stories, Grenville’s imagery is a joy. A vase shatters into ‘astonished pieces’ around a small girl’s feet. Looking at his newborn son, ‘Father thrust his chest out and clenched his buttocks, setting an example.’

All the dialogue is italicized. This both emphasizes it and makes it strange, apart, as the world is from Lil. It is most effective.

Lilian’s Story is divided into three sections, ‘A Girl’, ‘A Young Lady’, ‘A Woman’, and each has many mini-chapters with intriguing titles. Although exactly a third of the total in length, the childhood section seems weightier than the other two. This isn’t to say these later sections aren’t good: they are. But somehow I wasn’t aware of Lil actually ageing (though perhaps that’s fitting for Lil). Perhaps I’m just being greedy, wanting the book to go on.

Lilian’s story is full of ‘if onlys’. If only she’d had parents who appreciated her originality. Teachers who. Friends who. And yet ... had she been from the start more ordinary, more acceptable, she would never have hoisted herself into a tree at a boring garden party to have good talks with two unhappy timid young men, outsiders like herself. While the role-playing girls and boys stalk one another in the garden below, Lil and Duncan and Lil and F. J. Stroud form real, trusting, honest friendships which are another of the joys of this book.

Again, only Lil the eccentric could have forced a stranger on a tram to realize that she was far more than just ‘Agnes Armstrong, wife and mother of two’. ‘But I was still not satisfied,’ Lil recounts. ‘What else are you? ... That gave her courage, and she laughed recklessly and lifted her chin like a young beauty, and cried, Oh, what else I am would take a year to tell! and I had made her beautiful for that moment.’

Lilian’s story will make you very sad, very angry. It will also make you laugh. Above all it is a tribute to the strength of the human spirit – but yet the pity of it, Iago! the pity of it.

Comments powered by CComment