- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Randolph Stow’s latest novel, The Suburbs of Hell, may be read as a simple whodunit: a simple allegorical Whodunit. Like Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose, like David Lodge’s Small World, this novel sets out to intrigue the reader. The new genre, nouvelle critique, teases the reader’s vanity, the reader’s erudition at the same time as it engages with questions of a metaphysical kind – the nature of truth, reality, and for those concerned with literature – the purpose of writing today.

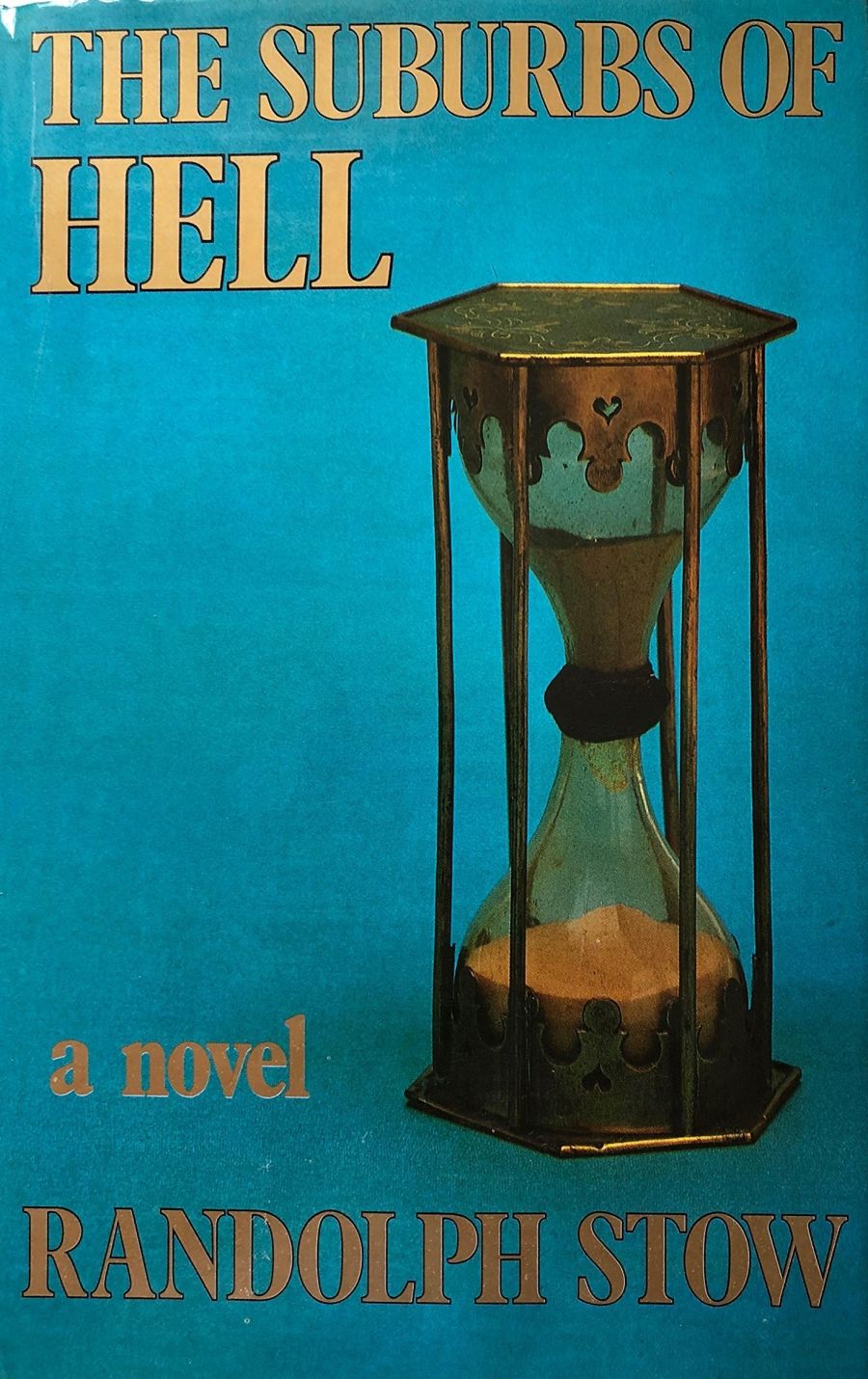

- Book 1 Title: The Suburbs of Hell

- Book 1 Biblio: Heinemann, $17.95 pb

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/XxyVO3

Stow, like many of the new novelists who speak to the initiated, is preoccupied with his art. However, the author as creator and destroyer takes on a more sinister aspect and the novel’s moral concern is linked with questions of the function of escapist literature and the responsibility the writer has in pandering to the reader’s desire to enter the imaginative world of death and destruction and be happy in it. Hence the use of the whodunit mode by Stow to teach and delight. Moral literature disguised as escapist literature pandering to two ‘evils’ in humanity, gossip and suspicion. Stow uses the central concern of a Whodunit, Death, the Great Mystery, to make subtle observations about human behaviour, its egoism and its frailty. He also uses quotations from Webster, Beowulf, Shakespeare, and the Bible, ‘whispers of immortality’, to expand its allegorical significance. From this delicately wrought novel comes the thought which has haunted Stow throughout all his work, that humanity is its own enemy – its fatal disease.

In The Suburbs of Hell, Stow has perfected the dual perspective which characterises his novels and which Leonie Kramer found to be incompatible – poetic symbolism and realistic description. Stow as creator and destroyer is the ‘thief’ who comes in the night, and ‘takes’ people’s lives. The writer is ‘A thief [who] is a student of people’. Stow tells the reader in the prologue, ‘I have stood in a pub and seen a face, heard a voice, and slipped out and entered the man’s house, calm in my mastery of all his habits.’ As a writer in the realistic mode, Stow has brought to life with delicate artistry, the characters whose lives are plotted and then destroyed.

It was then that he met Ken Heath. The boy capitalist, flushed and already slightly bloated with drink, was unbuttoned enough to want to know more about the black man with the Suffolk voice. So Sam told him the simple story of his life, and the tycoonlet exclaimed and pressed his card upon him. He was himself, he revealed, the owner of a taxi firm in New Tornwich; if Sam should ever be interested, there was money to be made. He was touchingly friendly, and Sam, who was no drinker, was taken by surprise several times on the winding estuary road.

Between the pages of this short novel, redolent with lyrical yet sinister ‘choruses’ which introduce each chapter, Death opens doors and disposes of those who are secure in their suburbs. This is an assault by the novelist on all who have grown complacent and secure in their belief that they are safe from wanton destruction.

Yet the moral, which is enunciated by the first person narrator who haunts the novel even when Stow assumes the third person, submerges in the telling of the tale of ordinary people leading ordinary lives and minding other people’s businesses.

It is not envy or anything of hatred that brings me again to this little place in the mist which I have known so long and wished no harm to. I have no quarrel with the figures – uniformed in blue jeans and fisherman’s jerseys, for the most part – passing quickly and alone in the dim distance … I wish them well, or well enough, and their offspring … No; it is never hostility or malice. Simply, it is correction, a chastising.

The allegorical level of the novel acts out this correction, this chastisement. Our obsession with Death, in the news or in fiction, has not the significance it had for the writers whom Stow quotes at the beginning of what I have called the choruses. For them Death was ever present and horrifying. ‘But the demon, a black shadow/ of death, prowled long in ambush, / and plotted against young the old.’ Today we have anaesthetised ourselves against it.

But Stow feels that the Death or Evil plotting against us comes in many disguises. The one Stow is possessed by in this novel is security. He quotes from John Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi. ‘Security some men call the suburbs of hell, / Only a dead wall between.’ The novel takes its title from this. Spiritual death has invaded the suburbs but Stow is not hostile nor malicious in his attack on humanity’s complacency.

His imagined reality draws the reader into the world of Harry Ufford who does not feel his narrowness, who displays, tattooed on his fingers, the paradoxes of life, L-O-V-E: H-A-T-E, and who is happy with his ‘brand-new bathroom’, ‘brand-new mirror’ and his father who wasn’t ‘such a bad old boy’. Out of the wisdom of his middle years Harry has learned to appreciate ‘warmth and freedom, the privacy of his own special place, the comforting profusion of all those things, so lovingly chosen, which he carried home to mark his patch’.

This world of Harry, situated by the sea, the world of Old Tornwich, is invaded by death. And the reader becomes the willing collaborator and conspirator with the killer who enters and proceeds to kill of Harry’s acquaintances. Stow’s soothing narrative unfolds a tale of violent death, drugs, and the pestilence of suspicion. He gives the reader a known, mundane, and prosaic town in which the neighbour is neither beyond reproach nor gossip. Stow insinuates us into the lives of the townspeople and we watch, with the killer, their simple skills of survival.

As the number of dead multiply in the town, on the pages, the reader should recall the early warning given by Stow, ‘I kind of envy you your imagination, young Killer. There is not all that much drama in Old Tornwich.’ But the drama spreads as more bodies drift through the pages. ‘He reaches for the ladder, but his fingers will not close on the rung. They open, they slip away. He drifts from the ladder’s foot, and closing his eyes, goes down and breathes his death’.

As the characters breathe their deaths, the great mystery looms, ‘Why them?’ Sometimes we know.

He lies along the seat, his knees drawn up. His hands press to his cheeks, for comfort, the collar of his sheepskin coat. He is attached to that coat, as single men grow attached to things. The smell from the hose was to him, when a boy, something exhilarating, a perfume. It smelled of liberation and promise. His father, the black British working-man, never owned a car, never had a licence.

Some narrowness, like Harry’s, Stow tells us, is accommodating. Other narrownesses, like prejudice, can become killers. We, like Stow, can be creators or we can be destroyers. The choice is there.

But often we escape from this choice into drugs, fiction. Linda De Vere is one of these characters, ‘cocooned in her warm sheets, wanting not to be born’.

She is a consumer of Rebecca, Gone with the Wind, and sometime reader of more genteel fiction, Jane Eyre or The Woman in White. ‘Of recent books, she loved The Thorn Birds, and quite liked The French Lieutenant’s Woman.’ She notices ‘the writing on the windowpane’ but the creator of lives and perpetrator of their death leaves the message, ‘in a lipstick which she had worn only once’. ‘NOT TONIGHT: SOON.’ To this kind of ‘playful’ message, Linda can only response ‘listlessly, a little fretfully’, ‘And what the fuck is that supposed to mean?’

No sense of allegory will invade Linda De Vere’s literary world. Of her escapism Stow says,

But most of the time she lets herself be led by the hand and the eye down familiar London streets of sweating, studio cardboard, through unlikely wreaths or boas of studio fog, to the recurrent meetings with ritualised horror.

She is soothed by the formalities of this emotionless dance.

While evoking the ordinary world of ‘figures – uniformed in blue jeans and fisherman’s jerseys’, Stow’s subterranean allegorical meaning emerges, ‘he looked down at himself, at his clothes. Jeans, fisherman’s jersey, donkey-jacket: anonymous’ – Frank De Vere, petty thief, drug peddler, possibly wife-killer, everyman. The physical world and the metaphysical world meld in Stow’s fiction.

When the cuckoo called he stopped, and felt a moment of desolation. The woods were suddenly so vast, the way out of them so long. To be alone was no hardship; but who could be certain that he was alone? That very place, all country peace, had witnessed a bloody and unsolved murder five years before. While the moment lasted, he could see nothing ahead of him but a lifetime of walking past trees and doorways hiding assassins and spies: lethal tongues, condemning eyes, working, so casually, for his destruction. That, he had to believe for as along as the vision was on him, was the life of a man among mankind.

While Stow whispers of mortality by interlacing his skilfully told tale of murder and suspense with a much older world of literary allusion, his novel’s message is optimistic for in it he confronts the suburbs of Hell, he does not escape from his moral obligation as a writer. Stow’s The Suburbs of Hell is a morality tale told by a voyeur, or as Harry mistakenly calls Frank, a voiture, a vehicle for his comment on writers of escapist literature: ‘How they have annoyed me with their diversions and sidetracks leading to no development; pathological killers of time.’

Stow hopes that ‘By me these shifting shapes fixed. After me, they may be judged at last.’ Whispers of Immortality.

Comments powered by CComment