- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Whorehouse as warehouse

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

After listening to Dorothy Johnston being interviewed on radio on her experiences in a massage parlour one would have expected a different kind of novel from Tunnel Vision. No doubt part of Johnston’s appeal as an interviewee came from the publicity blurb which announced that “she worked for a time in a massage parlour in the late 70s, and became involved in a conflict in St Kilda over whether prostitution should be legalized. She helped form a Prostitutes’ Action Group. Though Tunnel Vision isn’t autobiographical, the inspiration for it came partly from this experience.”

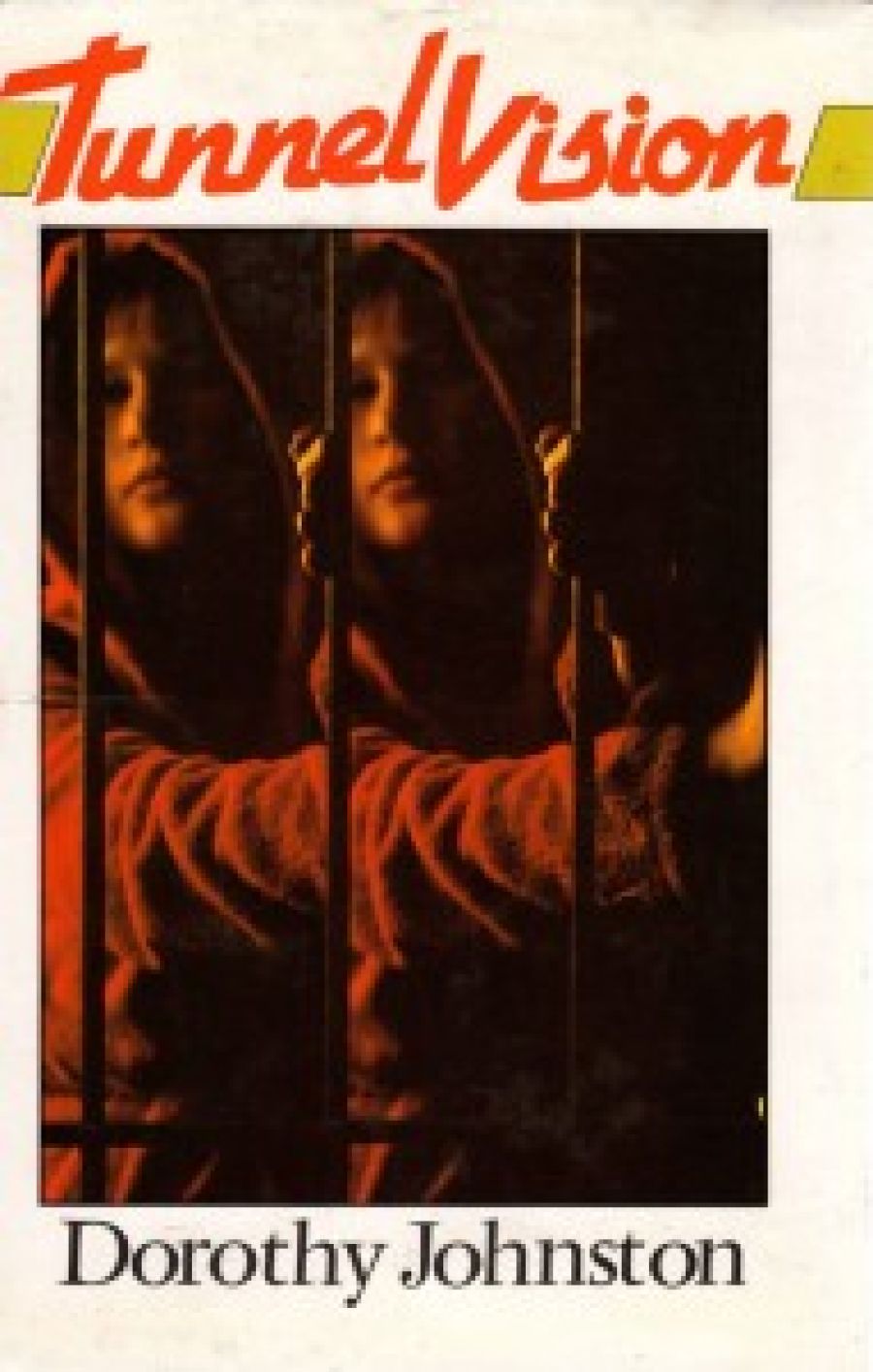

- Book 1 Title: Tunnel Vision

- Book 1 Biblio: Hale & Iremonger, 98pp., $7.95pb

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The narrator, Lilly, comes by her name by a process of transmutation – from Little, to Lil, to Lilly. She is the novitiate of the trio in Harry Cod’s (!) enterprise – Maria’s Massage Parlour. Lilly, the everywoman prostitute with a higher degree of sensitivity that most men expect when they seek solace in a house of ill-fame rather than in their house of mortgage, comes to find her place by accepting an offer she can’t refuse from Harry Cod. Harry (*Tm a living proof against King Lear and the first law of thermodynamics”), sees himself as theatrical manager, illusionist, alchemist, “something of a maverick”, doing something for the unemployed. Lilly’s and Johnston’s attitude to this personality is the same; there is an appreciation of something more than “the sound of money in the bank... a hint in his brief, businesslike, engaging manner, a promise at the back of his showbusiness eyes”.

Johnston has a subtle irony which trickles through the most innocent sounding statements. ‘I’ve found the secret of the transmutation of matter, the power to create ex nihilo. I’m a mining man’. Although Johnston appears to be celebrating whores-with-hearts-of-gold, and often the evocative passages of sea and place reinforce an idyllic and romanticized vision of St Kilda and Port Melbourne, the novel’s message is contained in the metaphors of change and corruption. These are light and whimsical in the opening sentences of the novel:

On a cold autumn morning, Harry Cod did the salada run. Down Flinders Lane the sun shone thin, dry and white, picking salty holes through the crust of the Rosella coat factory.

At the end of the novel, “The wind stalked round the tent poles like the troubled king round the olive grove at Delphi, and the ground reverberated with busy noises of preparation.” Throughout the novel decay, and its insidious odours, creeps into the innocent world of prostitution.

Lilly, Freda and Maria are the trinity who receive the flotsam and jetsam of capitalist society – they take in the old, the lamed and the sick at heart.

There was a look in his eyes that reminded me of the genials who continued to find their way to us across the flooded city, under new umbrellas that covered them from head to foot. It was the ready, triumphant look of men who, at their time of life, were swimming against the tide.

The trio, cynic, mystic and novitiate, work in a “warehouse, which, with the help of salt air and wood borers, was gradually condemning itself”. The corruption from without and within finally pervades the warehouse come whorehouse.

It was a smell like a cupboard closed on old menstrual blood, and feet that have been running in sandshoes, and classrooms full of boys on a wet day. It was worse than all of these and still different, containing an addictive secret ingredient like Coca-Cola.

The novice chooses affinity with the mystic Maria whose tunnel vision offers escape from the hard reality of the clients into the effervescent world of the imagination. In this world the men “came to remember and forget”. It is a recaptured Eden, “a dimly-lit world, where each day a performance was repeated simulating love; into the world of sex which, by common consent, we refused to call sex, but instead massage, the boldest euphemism of our times.”

Johnston’s narrative works towards an apocalyptic conclusion but in terms which are low-key, prosaic and deceptive in their intent. Maria finally closes her mind, her vision into reality. She seeks escape in theatrical production of life and ends in a hospital bed.

The last time I saw Maria, she was sitting in a hospital bed. Her hair was quite grey. The nurse had combed a few dry strands across her forehead. Her hands were covered with brown patches. Her eyes were flat-surfaced, two dimensional, like a pond with scum on it. Those familiar eyes had spilled their secret all over her face, and it was one that nobody wanted to look at.

The spare style is livened by ironic wit, apposite metaphor and an insinuating cadence. My initial response had been one of disappointment because I had been misled by hearing Johnston on radio. But the novel teased. I re-read it. It was a different novel. I still have some reservations because the sympathy with which Johnston creates her characters makes them intangible, soft creatures of fantasy even though their dialogue often counters this notion. Yet there is no doubt that Johnston’s work is not a romance of lower life but an attack on the soft self deception inherent in us.

Comments powered by CComment