- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: When solutions are too easy

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The dust jacket puff tells us that Gary Langford’s new novel is “in the richly bizarre vein of John Irvine”. For some this will be a less than enticing recommendation. But Vanities is a less sentimental book than Irvine could have written. Irvine’s humour is the measure of his characters’ uuntrammeled imaginativeness in an otherwise pedestrian world, a measure this reader finds fatuous. While Langford does have a tendency towards Irvine’s brand of brittle whimsy, his characters’ wit is a dissembling, defensive style, an indication of their vulnerability. He is determined to indulge neither his characters nor his readers with whimsicality.

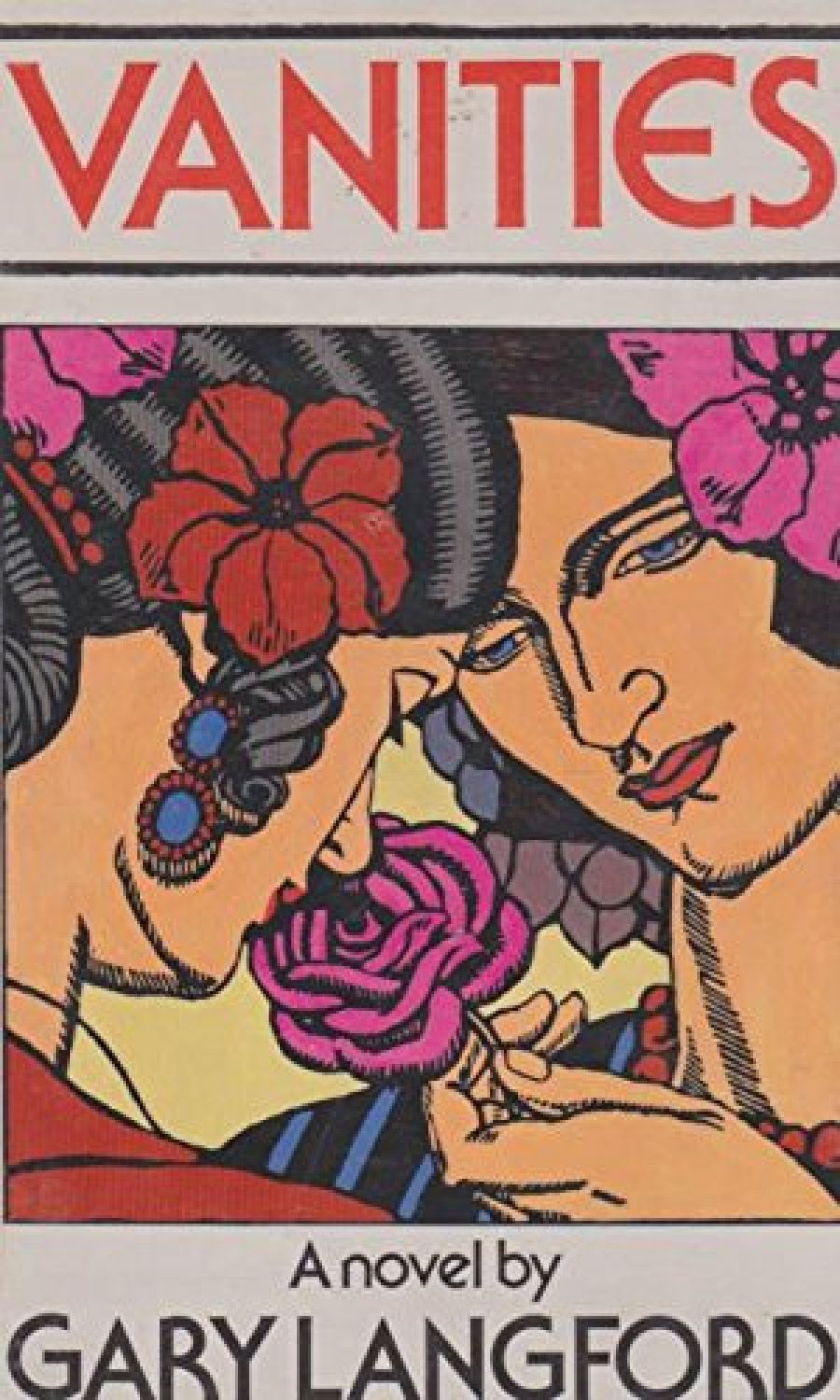

- Book 1 Title: Vanities

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan, 212p., $14.95

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

We need people to remind us all that normal doesn’t exist – there’s simply degrees of neurosis.

Julie Baxter’s mot might stand as an epigraph for the novel as a whole and Langford sees himself as the necessary truth-teller. In the course of the novel he glances at the brutalities of second world war Europe and of Australian mental institutions, the sentimental agrarianism of the hippy movement, exploitative television advertising, the Australian protest movement against the Vietnam war, the rise and fall of the Whitlam government, the oppression of women and homosexuals, and the egotism of student radicalism. The novel carries a dedication to “Alcoholics ... in particular to those alcoholics who have learned to live with themselves and their disease.” Unfortunately the truth of all these matters as the novel understands it is not very profound; nor does it convince us that this grab bag of issues intrudes on private lives to the extent that relationships arc inevitably rendered neurotic. The novel’s ambitious effort to contextualise relationships remains very superficial.

The emphasis given to the assassination of John Lennon provides a case in point:

Just before Christmas of 1980 we woke to find that John Lennon had been murdered, shot down on a New York street. The news came through late morning. Mother and I stood in the kitchen, staring at each other in shock. The fucking bastards! we both said together. The radio stations were playing tributes and you realised how much the music was part of the tapestry of your life… Lennon’s murder drifted into the dead heart of our family... It was a beautiful clear day and you could stretch your eyes away out to sea... It was hard to visualise a cold evening in New York and a quiet figure slipping out of the shadows with a gun in his hand.

It is extraordinary how often this event has been taken by popular myth-makers as a disenchanting and oppressive sign of the times. Langford’s imputation of special significance is no more convincing – we require a less melodramatically assertive, more inward account of just how the gratuitous murder of a pop-singer in New York, whose idealism (represented here by the jejune lyric of “imagine”) was, on the most generous estimate, grotesquely naive, can justify Lyn Baxter’s forebodings that the Australian sunshine is an illusion beside the gloomy New York reality, that the domestic life of the Australian kitchen is determined by New York thuggery.

But the novel’s focus is domestic rather than social and it is in his account of an affluent but troubled family for whom “the cup of hardship runs over” that Langford is most repressed beneath the flip protective surface of Lyn Baxter’s narration. One wonders, though, whether Lyn’s effort of good faith, her determination to understand her own and her family’s disappointments and dis-enchantments, is really sufficient to the therapeutic task of reconciliation it is said to achieve. Her movement towards self-appreciation is characterised by a tendentiousness which represents only the shallowest kind of self-knowledge:

You can’t stick at anything for more than two minutes, said successful . Some moving detail is

Tom… who’s to say you’ll stick at being a mother alone? He had a point. If I couldn’t picture him being a sole parent, I couldn’t picture myself either. I was still worrying about my motives for having a baby, at best they were vague and at worst they might be possessive –…

And the related rapprochement with her mother is based on pure nostalgia. These solutions are, we think, much too easy.

Comments powered by CComment