- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Three poets as “The Watcher”

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

All three poets use a personal voice to summon forth their immediate universe. Ryan and Brown are very much entrenched in their respective sub-cultures whilst Burke is essentially the polemicist, the observer of life in her native Newtown.

Ryan’s collection is permeated with the language of a very bold imagination: “As a brain leaks out from its tiny emotional field”; “Smile like a white ladder. That’s their famous trick”; “His straight and yellow skin steers his parents’ car”.

- Book 1 Title: Selected Poems 1971-1982

- Book 1 Biblio: Redress Press, 147pp., $9.95pb

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

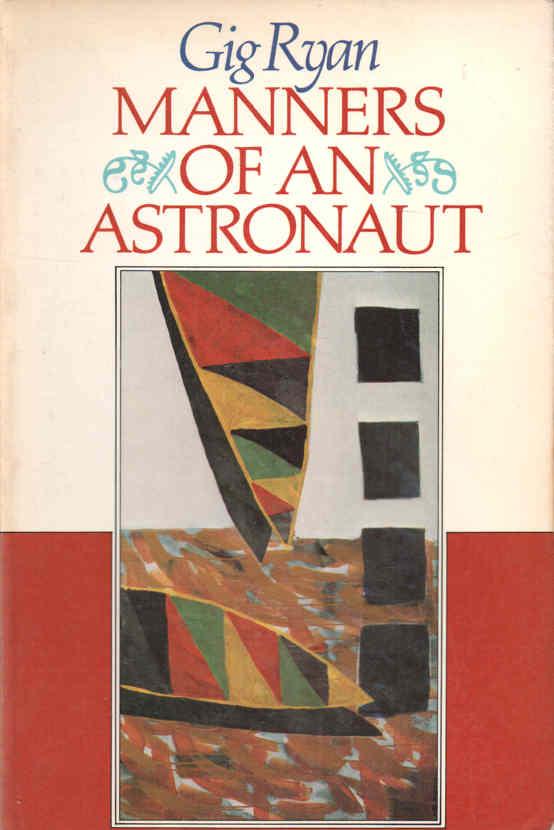

- Book 2 Title: Manners of an Astronaut

- Book 2 Biblio: Hale & Iremonger, 80pp., $7.95pb

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

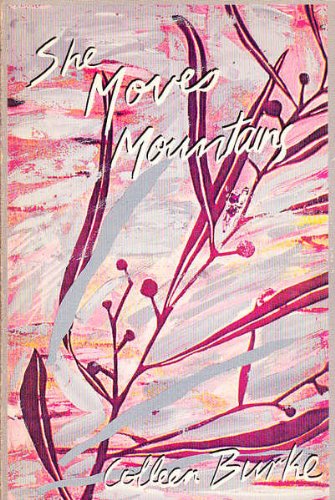

- Book 3 Title: She Moves Mountains

- Book 3 Biblio: Redress Press, 96pp., $5.95pb

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

This is unfortunate because some of the pieces carry a certain power once we come to terms with the welter of image, especially – ‘In Blue Craft and Two Minds’, ‘Loose Red’, ‘Going Backwards’, ‘Smile Like A White Ladder’, ‘Manners of an Astronaut’ and ‘So Far’.

No matter how compelling certain parts or individual poems may be, however, the meaning is far too often obscured by the sheer weight of image and gymnastic metaphor as the reader is left in doubt as to what the poet is really saying.

Pamela Brown’s collection of selected poems shares many similar ingredients to Gig Ryan’s. Both poets are part of a generation searching for identity in a youth culture of ‘Rock’ heroes, the changing tide of relationships and the presence of drugs. Unlike Ryan, however, Brown can more readily sustain the reader’s interest by her topicality, the way she steps out into the sub-culture around her and sign-posts her emotive universe. Early pieces in her first two collections, Sureblock and Coca-bola’s Funny Picture Book might strike the reader as curiosities now, some ten years on, but they retain a certain poignancy. We learn of the heroes, those larger than life that played the stage for those like Brown who grew up in the ’sixties – J. Joplin, J. Hendrix, B. Jones, F. Farina and N. Cassidy.

Brown’s best pieces come from Cafe Sport (1975-1978), where she uses her simple directness and powerful clarity to portray her images:

will we settle for swaying trees

ocean sunsets

stifled moons eclipsed dark mysteries

or skyscrapers selling old coke bottles

for cigarettes in the end

(‘Alternatives’)

Brown also impresses when she toughly asserts her right to be a woman on her own terms:

g’day riflehead.

i see you shot the mirrors down

while i slept like a splinter

you were a sheet to me

i ripped you up for rags

made myself a bandage (‘G’day riflehead’).

Pamela Brown’s selection of poems culled from previous books reflects her progress as a poet and individual. Although her concentration on self-referencing limits the breadth of her canvas, she does sustain the reader’s interest through her topicality and what she stands for as a fearless observer, a fighting woman with a distilled sense of humour.

Of the three poets, Colleen Burke stands apart. Her poetic vision embraces substantially different sensibilities and she almost totally preoccupies herself with the world outside. Unlike Ryan or Brown, Burke in She Moves Mountains is not concerned with exploring emotional interplay or the psyche.

Burke invites the reader to share the world of her native Newton; its urban landscape, the sea, the weather, the changing face of nature and the wonder of baby Burke. Her style is simple and consists for the most part of the daily vernacular:

Light stirs

probing dusty dreams.

Black cats

glide arching their backs

claws bright in darkwood (‘My day has begun’).

At her best Burke manages to be evocative:

I was born and bred

at Bondi under the smell

of surging surf and sewerage

The scent of lonely Sundays

and trams hurtling to the cluttered sea.

Asphalt days (‘Born and Bred’).

The strength of this collection is the large canvas it paints. Poems change in format and there is variety in the subject matter, some of which could be deemed socially important. There are some poems with fine images and crafting, some just slabs of prose and one, ‘Eliza Emily’ with shades of internal rhyme.

Burke’s poetry can essentially be divided between that of the lyricist and that of the polemicist. It is when the author dons the cap of the latter that the reader becomes disappointed; there is no attempt at shaping the poem. Instead the reader is treated to what could easily pass as copy from the morning news.

The subject matter of Burke’s polemical pieces is important in the broad spectrum of social justice. It would have a far better chance of being remembered if it weren’t treated as just another mud brick or piece of Vita-Brits, as is the case in ‘If We let them’, ‘It’s all in the mind’ and ‘If that was your wish’:

But you know if we let

them they’re going to bulldoze everything – even the wildflowers

the waratah, wattle and curving

kangaroo’s paw, and before

the rivers run backwards we’ll

drown in their stupidity and

choke in their duststorms.

If we let them.

Of the three poets, Burke is potentially the most interesting. Vernacular is her strength and her limitation, particularly when under-revised drafts leave the impression that the poet too often falls into trivia and resorts to the pedestrian.

Comments powered by CComment