- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Sport

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Despite its faults, this book has the merit of being the first biography on the legendary Australian batsman, Victor Trumper (1877–1915). Young cricket lovers of today may well ask what feats of batsmanship Trumper performed to deserve this handsomely produced volume about him. After all, his test average was only 39.04, not to be spoken of in the same breath as Don Bradman’s 99.96.

- Book 1 Title: Trumper

- Book 1 Subtitle: The illustrated biography

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan, 232 pp, $29.95

The old-timers tell us it has a lot to do with the consummate grace and artistry of his stroke making, and not a little to do with his combination of audacity and physical strength. Famous English cricketer C.B. Fry summed it up this way: ‘The gracefulness and vigour of his strokes are due to an almost perfect natural balance and to his remarkable wrist power. Even in his hardest driving his wrists do the work. His body weight comes into the stroke, but never with any labour or tug: he has a free arm swing, but this is always subordinated in such a way as not to disturb his poise.’

Mallett gives an account of his achievements and wisely sets them in the context of Trumper’s time, when the tempo of life and social milieu were vastly different from our own. Trumper toured England four times: 1899; 1902, 1905, and 1909. These were the days when some batsmen still wore open slotted pads; pitches were uncovered, a hit out of the ground earned only five runs, and some cricketers played the game for fun. One of his greatest triumphs occurred during the fourth test at Old Trafford, Manchester, in 1902. Mallett reconstructs a wicket-by-wicket and sometimes ball-by-ball description of that famous match, which Australia won by three runs. Test matches in those days were three-day affairs, so batsmen had little time to play themselves in if they wanted to win. So Trumper was the right man to open for Australia – his batting philosophy was to try and hit every ball for four. The pitch was treacherous, having been affected by rain, but it held no terrors for Trumper. Without ado, he proceeded to carve up the English attack with his long-handled drives and ever-so-late late cuts. No doubt the spectators saw a few of his peculiar ‘dog’ shots whereby he would lift his left leg (like a dog) and despatch the most venomous yorkers in a flash to the square leg boundary. Batting in this daring vein, he reached his century before lunch. He was the first batsman to do this. In the seventy years since Trumper’s death, only three others have achieved the feat: Macartney in 1926, Bradman in 1930, and Majid Khan in 1976.

Part of the Trumper legend consists of stories like the following. Clem Hill was battling with Trumper during the latter’s first test innings at Lord’s in 1899. At the tea interval, Hill complained that bowler Townsend was worrying him. Trumper told Hill that he would take Townsend’s bowling and was as good as his word. After tea, Trumper flayed Townsend to all parts of the hallowed ground. A relieved Hill got his century, while Trumper, as if rewarded by those gods who favour the brave, scored his first test century.

This unselfishness not only endeared Trumper to his teammates but to all manner of people off the field as well. There are stories of urchins coming into his Sydney sports store asking for discarded equipment. Trumper would give them a full set of new gear, free of charge. (Maybe this was why he failed in business so often!)

There was a stubborn streak to his nature too, which brought him, and five other prominent cricketers, into conflict in 1912 with the newly formed Australian Board of Control for International Cricket. Overseas tours until then had been organised and managed by senior players who divided most of the profits among the team. This left little for clubs in Australia who were struggling to keep afloat financially. When the Board acted to try and stop player-organised tours, it put itself on collision course with the Big Six leading players: Trumper, Hill, Armstrong, Ransford, Carter, and Cotter.

They threatened not to tour England in 1912 unless they had more control. The Board refused to negotiate. Tempers flared, personal antagonisms developed to the point where captain and selector Clem Hill had a stand-up ring-a-ding fist fight with a truculent fellow selector. The upshot was that the Big Six did not tour and the Australians took a hiding in England. One of the faults of the book concerns Mallett’s use of Trumper’s diary of his 1902 tour of England. The expectation from a personal diary is that it will reveal his real thoughts about his performances, his team mates, the opposition, crowds, umpiring decisions, etc. But nothing like this emerges. Typical examples: ‘Thursday, 1 May: Practice – all day. Went to Ben Hur at night – Drury Lane.’ 15 May entry: ‘Essex match. Nothing but rain. -Got a few wickets. Wrote letters.’ And who could possibly get worked up about his 22 July entry: ‘Rained nearly all day. Made 296. 3 for 148 in 1 hr 20 minutes. Self 85.’

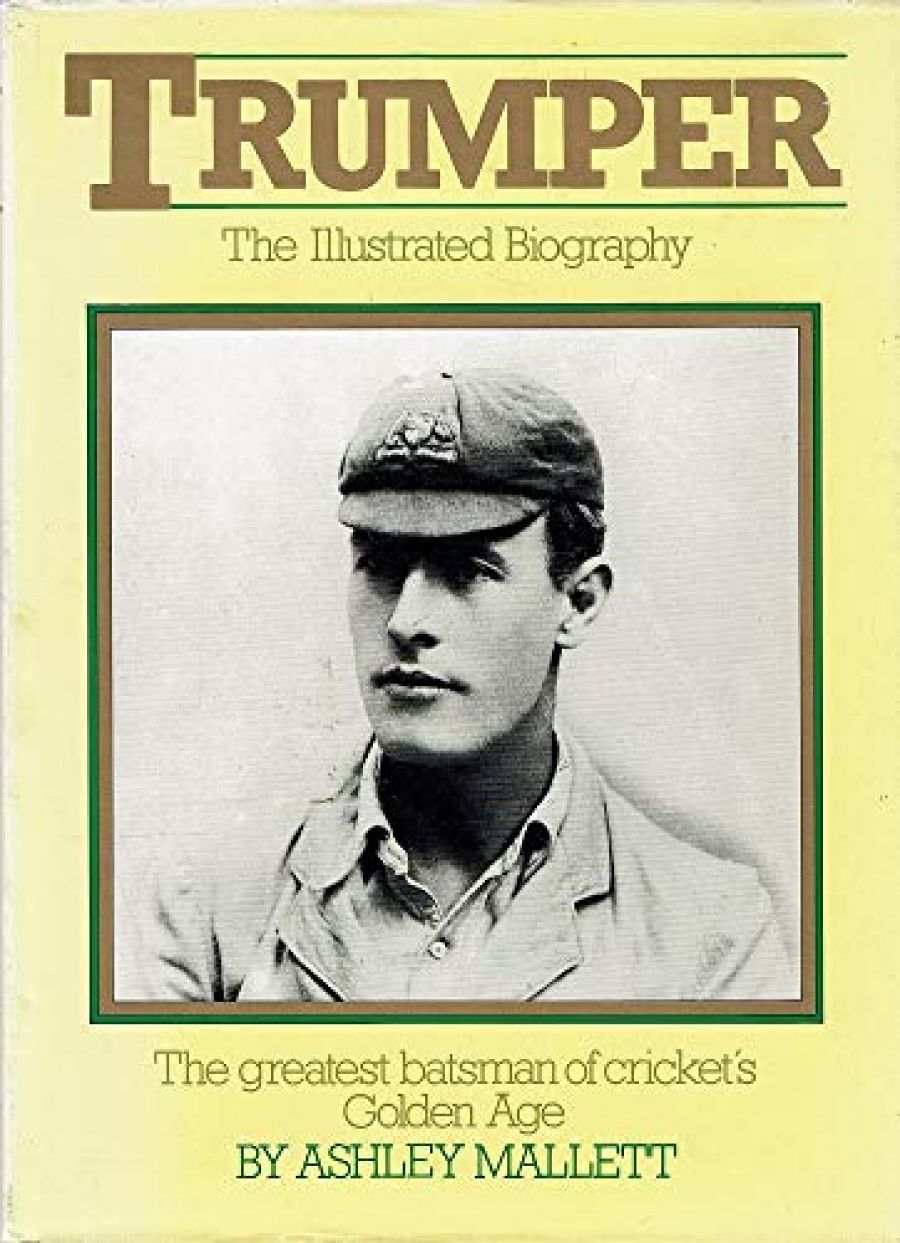

When it comes to the selection of photographs for this volume, Mallett was at a disadvantage. The limitations of the cameras in those days made it impossible to take good action shots of cricketers on the field of play. Consequently, there is not one shot of Trumper in action during a match. As if to compensate for this lack, we are confronted with an over-abundance of posed shots of famous batsman shaping up at the batting crease (some twenty in all). The best illustration in the book is not a photograph but a cartoon taken from a 1909 issue of Punch. It shows some London urchins playing a match out in the park. The batsman is saying to his mates: ‘Tell yer wot. You be England, and I’ll be Victor Trumper!’

Mallett’s text is not easy to read because it contains too many clumsy expressions and awkward sentences. It isn’t improved, either, by a liberal sprinkling of typographical errors. The worst example of the latter concerns the name of the manager of the Australian team to tour England in 1912. On page 122, he is six times referred to as Mr Grouch. Seven pages later he changes to Mr Crouch (three times, no less). On page 144, he reverts to his former identity of Grouch. And on page 193 he reaches the climax of his identity crisis by changing back to Crouch. As if this isn’t confusing enough, the mistakes are blindly transferred to the Index. Yes, both names are enshrined there, with three references alongside Crouch, Mr G.S. and two alongside Grouch, G.S.

In spite of the carelessness of the writing, shortcomings in the editing and negligence in the proofreading, the book will have sales among the keenest of cricket lovers, merely because it is, as the blurb on the dust jacket claims, the ‘first comprehensive biography of Victor Trumper’. But discriminating buyers may wonder whether it isn’t overpriced.

Comments powered by CComment