- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A colleague asked if I thought that Elizabeth Jolley’s Foxybaby might have gone ‘over the top’. I assume she meant that the book might be ‘too much’ because the function of its preoccupation with (say) crime and sex, including incest and homosexuality, was not immediately apparent. The question is a reasonable one, but for two reasons I don’t think that her latest novel does go over the top: there is no theme used or technique employed in Foxybaby which has not appeared in Jolley’s writing before; and, ad astra (perhaps per aspera or per ardua), the book represents a logical but highly imaginative development from her most recent work.

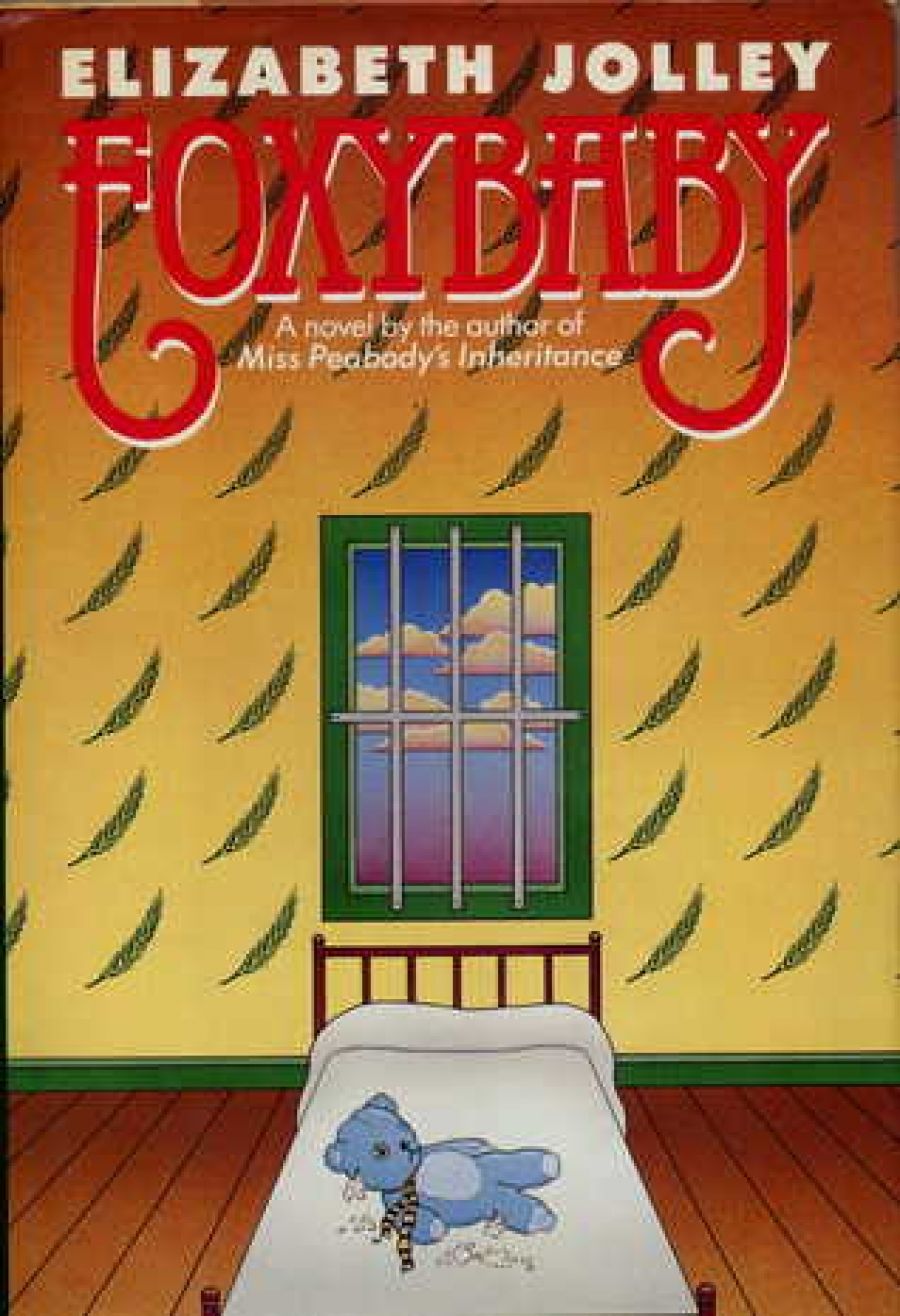

- Book 1 Title: Foxybaby

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $19.95 pb, 261 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/A7XNo

The petty crimes go back to her first book of short stories, The Five Acre Virgin (1976). There are several examples, but the funniest one is where a woman cons a doctor who has bought her land into a ‘gentleman’s agreement’ which allows her to take off just one crop before she vacates it – and then she plants a jarrah forest. There is murder by omission in The Newspaper of Claremont Street and by commission in Palomino. Incest figures centrally in Milk and Honey, where the title might be taken either as a sacred allusion or a profane metaphor. As for lesbianism, Palomino focuses on it soberly, intelligently and sympathetically, and in Mr Scobie’s Riddle Frankie and Robyn are manic devotees. Nor does male homosexuality make its first appearance in Foxybaby, although it is foregrounded here more than usually. Readers should think back to Jolley’s short stories, like ‘Adam’s Bride’ in Woman in a Lampshade (1983), where it is subtly hinted at, or ‘The Fellow Passenger’ in The Travelling Entertainer (1979). It is also implied in Jolley’s first novel, Newspaper, where the cleaning lady sometimes surprised people in their nakedness: ‘If a bathroom was occupied she would say with a nod, sucking in her cheeks, clattering her pails and brushes, “Excuse me, gentlemen, I’m about to do the floors”.’

As for techniques, Foxybaby is a veritable compendium of the various ones Jolley has developed over the years – dialects and foreign languages, fragments and run-on sentences, generically named characters (Miss Rennett, Mrs Crisp), curious literalisms (‘she thought of the death of Chekov in her brief case’), overheard and/or misheard conversations, visions seen through windows and in mirrors, odd notes and placards, extensive allusions to literature and music·and (of most interest) memories, dreams, imaginations/speculations, texts within texts and various glosses on them all.

Elizabeth Jolley is rather like a teller of tall tales. She presents outrageous things right from the beginning of many of her stories, but that only conditions the reader for still greater ones to follow. For example, it is a typical Jolley audacity to begin Milk and Honey with the line, ‘This was the street where Madge, suddenly worried that she had forgotten her tampax, drove slowly, unconcernedly, taking up the whole road while she fumbled mysteriously to find out.’ So, in a way, my colleague was essentially right-headed in her observation, because Elizabeth Jolley’s fictive world has often been a frantic one peopled with low-life characters· involved with taboo subjects and Foxybaby is insistently that kind of work. But Jolley’s most recent novels have taken a specific direction which one can see clearly, even if one cannot define it perfectly – a direction – that gives richer meaning to Jolley’s typical themes and techniques, To understand this fact, readers should know that Palomino (1980), Scobie (1983), Newspaper (1981) and Milk and Honey (1984) were all written, more or less in that order, from the 1950s through the early 1970s (and note that Scobie·precedes Newspaper). Thus Miss Peabody’s Inheritance (1983) – although published before Milk and Honey – and Foxybaby were both written in the 1980s and are her only novels which really can be used as accurate indicators of her current direction.

In Peabody Jolley works with metafiction more extensively than before: a reader who has been corresponding with a novelist becomes so engrossed in the latter’s current work-in-progress that she actually expects to meet characters from it in the streets of London; indeed, Miss Peabody becomes so involved that she flies from England to Australia to be at the bedside of the ailing authoress, now her heroine, only to become aware – and then not fully – that the woman’s life was quite different from her stated epistolary and implied novelistic descriptions of it. Throughout Peabody there are hilarious and touching scenes; and throughout the novel-within-the-novel there are the same, including literally bed-breaking ones where lesbians of various sizes and ages and degrees of sobriety practice everything but noli me tangere.

In Foxybaby, Alma Porch is the counterpart to Peabody’s novelist, Diana Hopewell. She has been asked to be a tutor at Trinity College in a wheatbelt town where sexually and financially over-charged students will follow The Better Body Through the Arts Course. The theme is meant to justify serving lettuce leaves with lemon juice for breakfast, a raw carrot for supper. But for still another large fee, broiled lobster, chateaubriand, chicken, veal, and ham are surreptitiously available late at night, along with- various fine wines, turning the Boy Scout’s mens sana in corpore sano exhortation into a clean-mind-clean-body-take-yourpick dilemma. There are also the other usual Jolley scams, like pre-arranged car crashes to benefit the local fender-mender. There are homosexual affairs, like that of Josephine Peycroft, Director, with Miss Paisley, her Secretary, or like that between Anders and his boyfriend Xerxes. There is· heterosexuality, which is taking place between Anders and Mabel Harrow. There is even a potential deflowering when Alma is invited up to the attic for a harrowing experience with Mabel and her two young men. There is near-tragedy, when Miss Rennett is badly injured in a fall while being lowered from a gable window on a ladder tied to a rope – she was midwife to Anna by virtue of her brother’s being a vet. And there is suspense of all sorts, for example, when the Potter swallows her false teeth in an auto accident (she broke both legs) and everyone is left wondering if she’ll turn up smiling. In short, there is an abundance of black humour; all of the elements which Jolley’s very name stands for are here in stellar profusion.

Like Peabody, Foxybaby is metafictional for appearing to have a novel-within-the-novel. It is, though, more complicated than Peabody in that there is greater interaction between those two fictive worlds. The internal novel is unfinished, serving as a script for the students to act out. So the text develops day by day as Alma Porch keeps writing, the students keep improvising, the supporting cast – like Peycroft and her girlfriend as musicians – add their own interpretations, and the whole group’s performance itself is captured on videotape for discussions during the evening symposia. Much of the peripheral action by comparison or by contrast constitutes commentary on that text. For example, the video gear goes missing one day and is returned with a tape of Mabel Harrow disporting in the nude, filmed by her two hangers-on (mind, she says, ‘I was only massaging myself, a little body massage that was all ...’). Compared to these blue-movie post-prandial evening sessions, Plato’s Symposium, with Alcibiades’s hand on Socrates’s knee, is a Sunday-school picnic.

As in Peabody, some of the characters in Foxybaby become inextricably involved with the embedded internal narrative which deals with the trials and tribulations of a Doctor Steadman who has had an incestuous or near-incestuous relationship with his now not-so-foxy daughter Sandy, a psychologically unstable, sick (VD?) and heroinaddicted, young woman who has a baby son with the same physical problem. Anna Brown, who plays that daughter, gives birth during the summer school. Mrs Meridian Viggars, a worldly but wise woman who movingly plays Dr Steadman, experiences a profound conversion deciding to adopt Anna. There is a bewildering confusion of roles as the widow who plays the widowed incestuous man decides to adopt the young mother whose child is actually by the brother of the lesbian Josephine Peycroft. It sounds more confusing than it is, for Jolley handles it deftly. In part, a kind of clarity results from Jolley’s repudiating artificial distinctions and limitations imposed by too restrictive a view of sex and sex-related roles.

Other critics have rightly wondered how much of Foxybaby is ‘real’ and how much is ‘dream’. I would argue that the book depicts two worlds. One is the ‘real’ one, comprised of the introductory letters between Alma Porch and the people at Trinity College, along with the description of Porch’s setting off to drive to the college and finally arriving there on the very bus with which she collided. The second is a dream which takes place after her auto accident when, in a state of shock, she gets on the bus to complete the trip and then falls asleep. It is a dream which develops as she imagines the Foxybaby story and how it would relate to her and the others when she actually gets to the summer school. In other words, most of the novel is a dream. In simple psychological terms, the characters and events are interconnected because they are a reflection of Porch’s past experiences and novel-in-progress – the manifest content of the dream; and the implications of their ‘over-the-top’ activities – the latent content – are a reflection of Porch.’s psychic inhibitions and dilemmas. In fact there are many dreams and dream references in Foxybaby from the frontispiece quotations (Hardy and Bunyan) through the many daydreams and waking and dozing moments punctuated by yawns. Keys to any reading of the book are the early and late passages where Alma seems to sleep and then to waken.

My argument is supported by Alma Porch’s reference to the first two lines of Dante’s Inferno:·Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita / mi ritrovai per una selva oscura, which Porch remembers as ‘In the middle of the journey I came to myself in a dark wood where the straight way was lost’. Her incomplete quotation form lines 10–12 of the Inferno (I’ no so ben ridir ...)gives still further support to the idea when she translates them as ‘I do not well remember how I entered there, so full of sleep was I at the point when I left the true path’. Dante sleeps and has a vision, and so does Alma Porch. In Jolley’s Hell, however, the situation is much more ambiguous: Alma Porch enables the growth of Viggars who, in tum, becomes Porch’s Vergil. It is not the poet teaching the other; nor is it the reverse: it is Alma·nurturing Alma during the trip through the Inferno of her psyche. The ultimate question is whether or not it is a prevenient dream.·

Dante emerges from his infernal journey on Easter Sunday, but Porch still has some way to go. Like the character/dream figures around her – notably Rennett, Anna, Viggars –she must choose; and, like the main characters in her novel/dream she must be chosen, becoming thereby part of a whole and holy family. Grace is involved in Jolley’s concept of choice, and Foxybaby raises our hopes as to the possibility of its being manifested when Meridian Viggars says that she and Porch must meet again, at Easter. The situation is both biblical and existential, as was Dante’s.

Before Peabody and Foxybaby, Elizabeth Jolley’s works were often peopled with characters who were either passive (although pensive) or constrained from action because of fear: for and of the self, the other, and possible relationships between both. But with her two fine recent novels she has been minutely surveying the distance between one person and another: the other may not be far; but, until Foxybaby, there just hasn’t been any way.

If Foxybaby strives high, Jolley’s next novel might probe deep. Called The Well, it is to be published next year.

Comments powered by CComment