- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There have been two major cycles in Australian political rhetoric since the war. The first occurred during the postwar reconstruction period, from 1943 until 1949, when contest over a new social order impelled an unusually clear articulation of philosophy and policies by the contenders for influence – represented in public debate by Curtin and Chifley on one hand, and Menzies on the other. The eventual ascendance of Menzies and the dominant ideas that emerged from that debate informed our political life for the next two decades. Not until the late 1960s, when the Liberal-Country Party coalition’s grasp of events slipped, and when the new problems of the modem world economic system and Australia’s precarious place within it dislodged the assumptions engendered in the 1940s, did the debate about the nature of our policy gain a new edge.

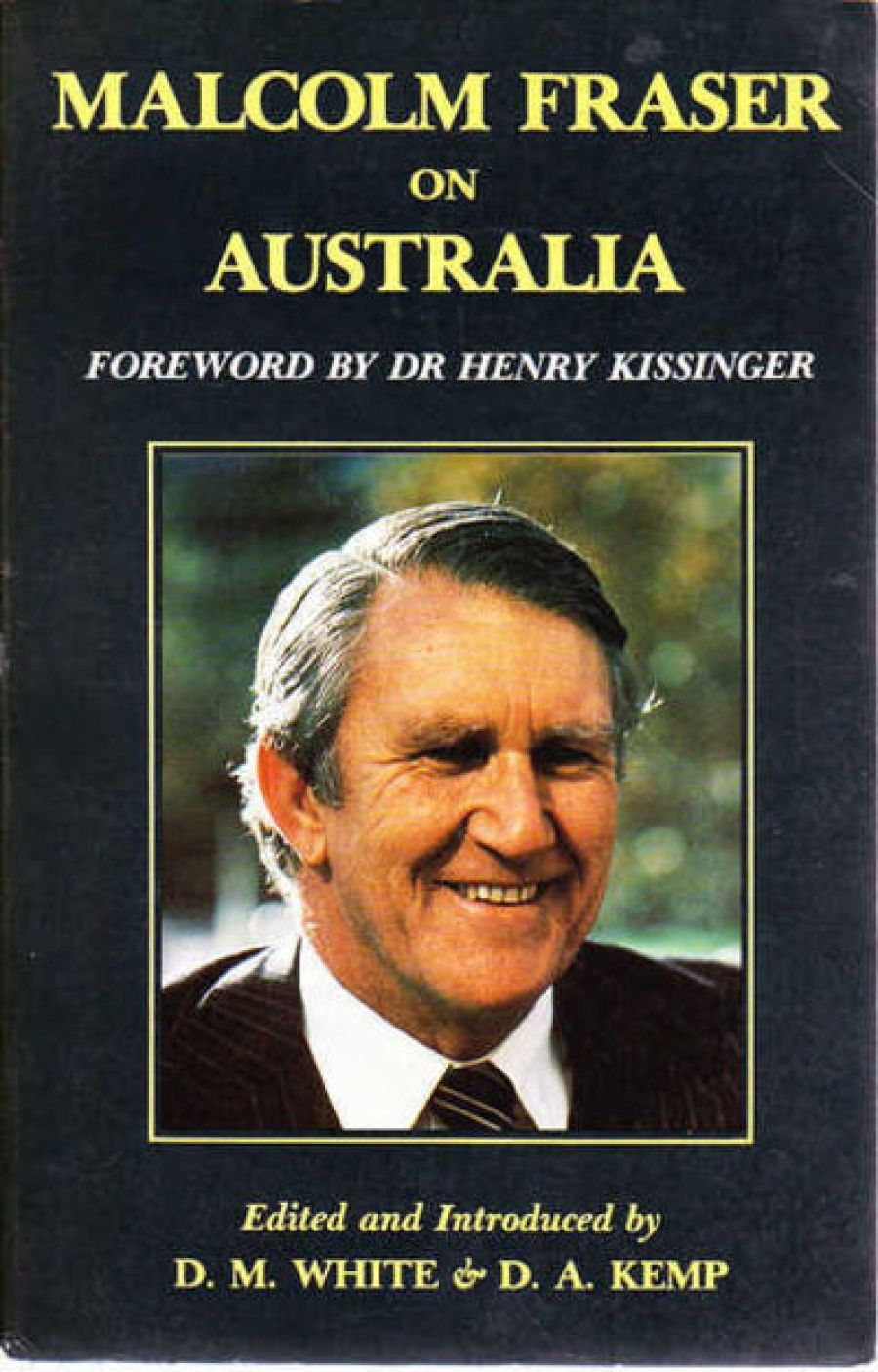

- Book 1 Title: Malcolm Fraser On Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: Hill of Content, 240p., index, illus., $18.95 pb , 0 85572 1596

The lead was taken by Whitlam who, in the process of ALP reform, brought a new emphasis to ideas in the political contest. It was his success that forced a new attention to philosophy and policy on the anti-Labor side – that in effect engendered the second major cycle in the debate about what Australia was to be. So preoccupied have we been with the volatile politics of Whitlam’s short reign, however, that most analysis and commentary has concentrated on one side only of the debate. Whitlam himself has enjoined us to ‘educate those who were not there’ – which has fuelled the Whitlam industry and motivated his own recent writings. But the fact that the Whitlam years created the context in which Malcolm Fraser could emerge as conservative leader, and that he too forcefully propounded a programme – over a term more than twice as long as Whitlam’s – has been overlooked. For the score of books wholly or partly about Whitlam, we have only a handful dealing in any way with Fraser. If the project of ‘educating those who were not there’ is serious, then the nature of Australian conservatism demands closer attention.

For these reasons, this collection of Fraser’s views is an important text – giving us as it were the missing part of the debate. The anthology was put together by Denis White and David Kemp, Monash academics who have themselves published on Liberal philosophy and Australian conservatism, and both of whom served as senior advisers to Fraser as prime minister. Each would have played a part in crafting Fraser’s speeches – though they strenuously deny that this bas any effect on the presentation of ‘his’ ideas. I remain unconvinced.

This is not a book for reading sequentially, from cover to cover. It is a compilation of excerpts from speeches and documents – none of them very long – arranged thematically and not chronologically. There are four very broadly defined ‘chapters’, dealing with Australia on the world stage, general principles (concerning Australia, liberalism and freedom), the nature of Australian democracy and its institutions, and running the country. Within each of these is a multitude of subheadings. The system of headings and subheadings is very useful for following through a particular interest in an area (say, economics, foreign affairs, or business-government relations) and even particular narrow concerns within an area (say, tax indexation, ASEAN, market regulation). The book is so clearly set out as to make it easy quickly to find Fraser’s view on virtually anything (racism, multiculturalism, the flag, the national gallery, educational curricula, for instance). This suggests it’s uses as a sourcebook. It also makes for handy comparison with the themes and categories in which Whitlam’s recent account of his government is organised. Against these virtues, it is something of an irritation to be dealing continually with such small snippets of text and to find not even the major statements (such as Fraser’s 1971 Deakin memorial lecture) printed in full. A sustained impression of the way a speech worked, or of the intellectual progression within it, is impossible to achieve in these circumstances. Surely we could have bad half a dozen of the major statements printed in full?

It becomes evident in their introduction that the editors’ purpose is as much celebratory and ideological as pedagogical – they are mirroring the Whitlam acolytes. In neither case is the exercise of interest. More to the point, however, is their assertion that Malcolm Fraser emphasised substance, and their concerted attempt to distil that substance. On the whole they succeed in this, and hence provide a useful service. That success is qualified by editorial strategies intent on producing an overdetermined reading. First, we are positioned in relation to the text by an introduction which lays out the central themes in Fraser’s philosophy very much in terms of his stature, intelligence, compassion and perception. An introduction isolating themes and ideas can be helpful, but the personal qualities allegedly associated with these should be self-evident in the text and taken as read. More useful would have been a more pointed discussion of the way these themes and ideas relate to prior traditions of Australian liberalism and conservatism, the extent to which they represent new departures, the degree to which they represent a coherent world view in opposition to (say) the Whitlam vision of social democracy. Similarly, we are guided in our reading of each of the chapters by an uncritical paraphrase of forthcoming argument – again an exercise that can be helpful in helping the reader to come to terms with Fraser’s views, but which in this form militates against forceful analysis. Here, too, we are missing the other side of the debate, the contextualising, that would assist the uninitiated in placing and assessing these views. They are to be read only in terms of their internal logic – which is to say that this book equally must be read alongside those of Fraser’s opponents.

What, then, of the logic of Fraser’s view of Australia? His central principle (to which the editors carefully guide us) is that freedom is the central basis of democratic society, and that it is always under threat. It is endangered when people (in the absence of external challenge) forget its significance – hence the importance of rallying national unity and discipline. It is limited to the extent that institutions, state or private, are allowed to grow and encroach upon the rights of the individual – hence the emphasis on limiting government and leaving choice about the nature of services to individual enterprise and initiative. It is always prone to attack from without – and hence the repeated warnings of Soviet imperialism, and the emphasis on securing alliances. It is limited by anything which impedes the proliferation of choice of individual consumers – and hence the need to deregulate business and encourage competition. It is also threatened, however, by the emergence of huge corporations over which individuals can have little control – and so government does have a positive role to play as a critical balancing force in the midst of large and powerful organisations.

Such views are familiar and unexceptional – which is to say, they have a general history and a particular Australian history which neither Fraser nor his editors sufficiently acknowledge. What gives them distinctiveness here is the manner in which they are phrased and utilized by Fraser, and to get a feel for this it is necessary to delve into the book. There is no question of his success in giving such principles persuasive form. To take an instance:

Society has immense resources for achieving what people want without the need for counterproductive intrusion by governments. These resources are the talents, the skills and the knowledge which people possess. Big government cramps these resources. Centralisation and big government never held out any prospects for the cause for freedom and civilisation, for initiative and creativity, or for the promotion of those values which lead to the advancement of mankind. The advancement of mankind comes fundamentally from the voluntary efforts of individuals within the framework of civility and of the rule of law which governments help provide … From the late fifties, through to the mid-seventies, the west failed to perceive the need for new policies, and by the time it did wake up, unemployment and inflation were both high and becoming entrenched … The tradition of freedom – which flays that the way to solve these problems, is to encourage people to use their skills, talents and imaginations – was subordinated to a reliance on government. Hardly anyone now fails to recognise that government had grown too much. Our policies reassert that freedom – not paternalism and bureaucracy – is the path to the way of life that most people want.

This is however rhetoric that assumes audience complicity, a recognition of the argument as self-evident. There is a heavy reliance here on undefined terms, on assertions unsupported evidence, on axioms driven home by dint of reiteration rather than demonstration – tactics which belie the editors’ insistence that Fraser was a speaker who emphasized substance and not flowery rhetoric.

It is also evident that such language fails to address any of the counter propositions that could be raised against all of Fraser’s principles: that freedom from regulation may entail the freedom of some individuals to exploit others; that freedom to choose types and levels of social services may preclude any choice at all for the economically disadvantaged; that freedom from attack may involve entering alliances that impede ‘Australia’s autonomy; that the proliferation of enterprises to service consumers’ whims might encourage the squandering and exploitation of resources to no socially useful end; that freedom for transnational corporations to penetrate our economy may preclude the possibility of economic control at a national level, and hence of any role for government as a balancing force, and so on. Fraser, in other words, is engaged in the rhetoric of persuasion, not in addressing a fully articulated argument. This is no more than we might expect of a political leader – but it should give pause to those who would claim for him the mantle of philosopher.

While this is a comprehensive compendium of Fraser’s ideas, in the end the. real test is not what was said, but what was done on the basis of what was said. There is not always a logical extension from abstract argument to practical policy, and we still lack the comprehensive history of the Fraser administration which would enable us to analyse how and to what extent these pronouncements affected practice. There is, however, enough here to suggest some qualification to the shibboleth that conservative government in Australia is to do with pragmatism and not ideas. A concern for a philosophy did inform the Fraser government. That said, it is also clear here that Fraser does not equal Whitlam’s intellectual breadth and vigour and capacity to inspire. It might nonetheless be the case that Fraser has remained the more influential, that, as White and Kemp assert, he set the agenda of deregulation and financial constraint that the Hawke government itself has taken as the measure of responsibility’. ‘He had administered a crushing intellectual defeat to “democratic socialism” and its objective of bigger government’ – a defeat which Hawke and Keating seem intent on driving home.

Comments powered by CComment