- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Gender

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A phrase like ‘And God so loved the world, she …’ has a radical impact on that most deeply ingrained convention; the contract underlying and validating much of Western culture that the logos is masculine and the power behind the logos is designated, generically, as ‘he’. Our culture is patriarchal; patriarchal power derives from God and that power is symbolically inscribed in language.

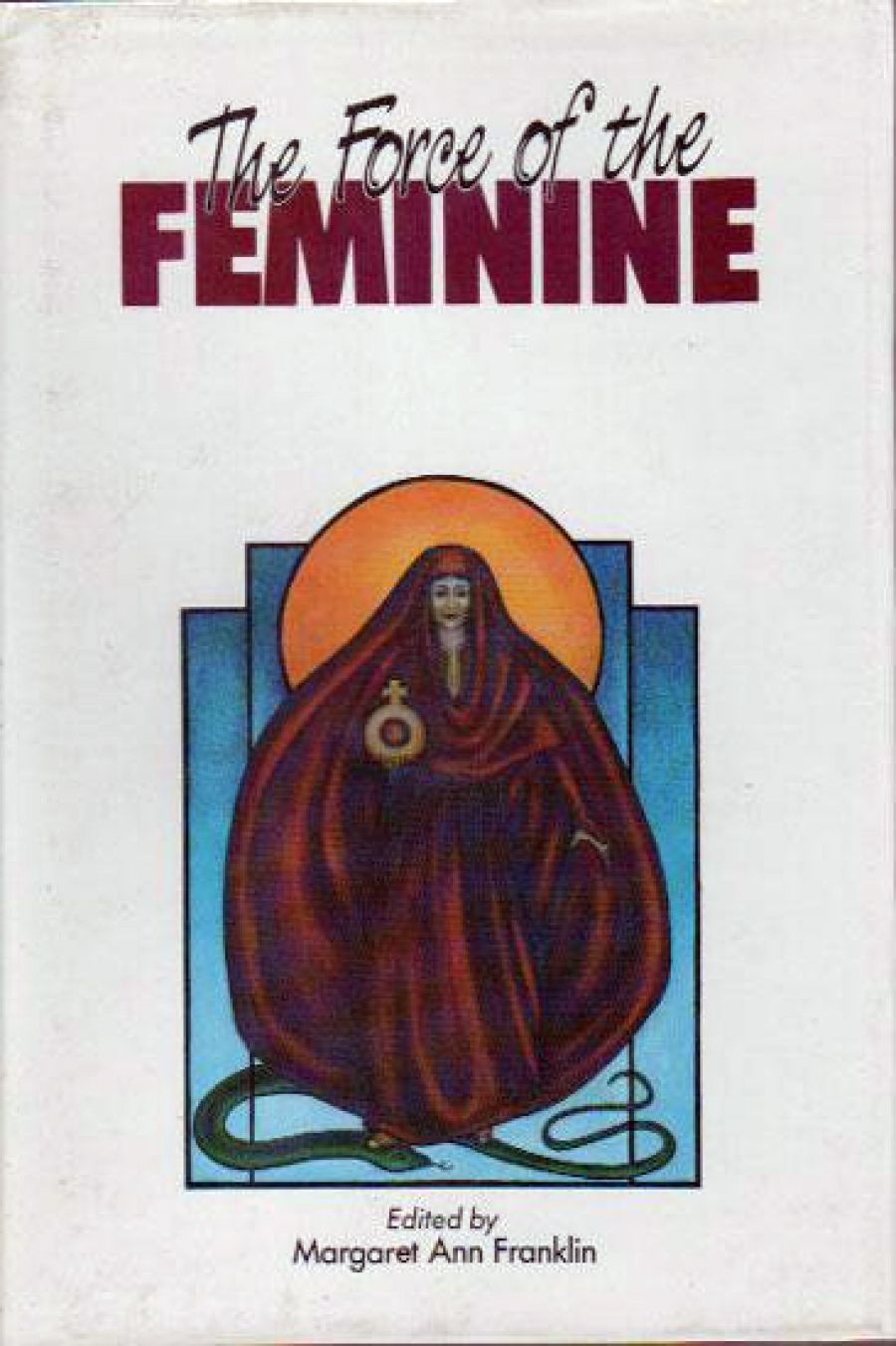

- Book 1 Title: The Force of the Feminine

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, 208 pp

Force of the Feminine is clearly situated within a Christian, theological framework, one which itself contains different positions and particular internal conflicts. Its contributors are all Christians (and all but one Australian). It recognises a contemporary, secular influence, the women’s movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s, which had an immediate effect on women in Australia, where Christian feminists set up an interdenominational group called Christian Women Concerned as early as 1968. The introduction sketches the history of feminism in and on the Church in Australia from the beginning. First, however, it carefully establishes the religious textual site of the volume, beginning:

There is a stirring today, felt in nearly every denomination in Christendom, which concerns the place of the ‘feminine’ in Christianity. This involves much more than improving the low status of women in the Church and changing patriarchal structures. It involves accepting the ‘feminine’ in God and loving our contra-sexual selves and calls for a theology which revives the ancient tradition of associating the Holy Spirit with God’s femininity … The Force of the Feminine has a message for all Christians …

Though much has been achieved, theoretically and practically, over the last two decades to improve that ‘low status of women in the Church’ and rethink religious structures and attitudes, much remains to be done. Miriam Dixson, a member of one of four task forces of the Australian Council of Churches Status of Women Commission set up in 1978, and reporting discouraging progress two years later, said: ‘It is not an exaggeration here’ in Australia to speak of the Church’s rigidities in the area of sexism … God is indubitably male, as are most of ‘his’ priests and ministers, and the dominant cultured of the Church as a patriarchal culture.’

Of course, changes positively affecting the status of women have occurred within the Church as they have within the State. But the current central focus around women and the Church on the question of female ordination masks other, deeper issues, according to the Introduction. The first concerns the proper place and administration of authority in the Church and involves and examination of the very of idea of authority in this most democratic of beliefs. More gravely, the matter of change in response to contemporary secular and historical pressures, against which the Christian hierarchy which looks to the word of God and the traditional beliefs and practices of religion as a kind of unchanging and unchangeable wisdom, is raised.

The essays in the volume address these and other questions. All are solid, thoughtful responses to these debates. Many, notably those written by women, draw-on personal experience, placing it in the framework of theological doctrine, church practice and feminist consciousness (sometimes theory), to organise and give it meaning. Marlene Cohen’s ‘A Clergy Wife’s Story’ exemplifies this many stranded approach. So does Veronica Brady’s contribution, ‘A Quixotic Approach: the women’s movement and the Church in Australia’, though her argument is more abstract, driven and informed by her sharp political interest and awareness. There is a great deal of insistence on the notion of spiritual androgyny towards which the opening essay ‘Women and the Church’ works. Men and women alike ‘have within themselves masculine and feminine elements’. True growth and change, personal and institutional, will be achieved when this is recognised and both elements fostered.

Another focus for these essays provides the opening to Maggie Kirkham and Norma Grieve’s piece ‘The Ordination of Women: a psychological interpretation of the objections’. Starting with the paradox: ‘The teachings of Christ suggest that the opportunities for women to serve Him are similar to those for men. The practices of the Christian church however, belie this possibility, particularly in the strong objections to the ordination of women to the priesthood’, these authors construct a closely argued, theoretical response to this contradiction between pious example and actual practice, using Dorothy Dinnerstein’s psychoanalytically based thesis that patriarchy and its manifestations can be understood as stemming from and sustained by ‘irrational and unconscious motives’. ‘In particular,’ they continue, ‘we will argue that justifications for the exclusion of women from the priesthood are more or less transparent expressions of attitudes exemplifying Dinnerstein’s claim that patriarchy is a social expression of the flight from maternal power.’

This volume is most accessible and is not to be located solely within an academic context. Its concerns affect the lives of a massive number of women (and men) and will be of interest to all these people. It also provides a comprehensive collection of contemporary work on an area of interest to Women’s Studies and Gender Studies courses, presumably also to those studying theology and working within religious structures. It is of great interest to me, and will be I think for others, since it uses and produces a very different kind of feminist politics from that which so often – and so fruitfully – delights in iconoclastic assaults on sexism in all its forms.

These essays all derive from that recognition basic to feminism, that the structures and practices of Western culture – of Christianity in this case – deal unjustly with women. Therefore, here is cause for anger and space for revolution. But without exception the tone of the essays is mild, judicious and equable. And the Introduction points out this difference. Theological questions:

cannot be settled simply by appealing io the sorts of considerations by which the community decides whether women should be admitted to the stock exchange … If Christians are to be Christians, they are in some sense under authority. They must try to relate all their thinking to what they take the will of God to be for themselves and the Church.

Herein lies both the strength and weakness, as well as the fascination, of this volume. It simultaneously questions the masculine dominance and patriarchal power upon which the institutionalised practices of Christianity are built and depend, yet must work within and acknowledge that still masculine authority.

Comments powered by CComment