- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

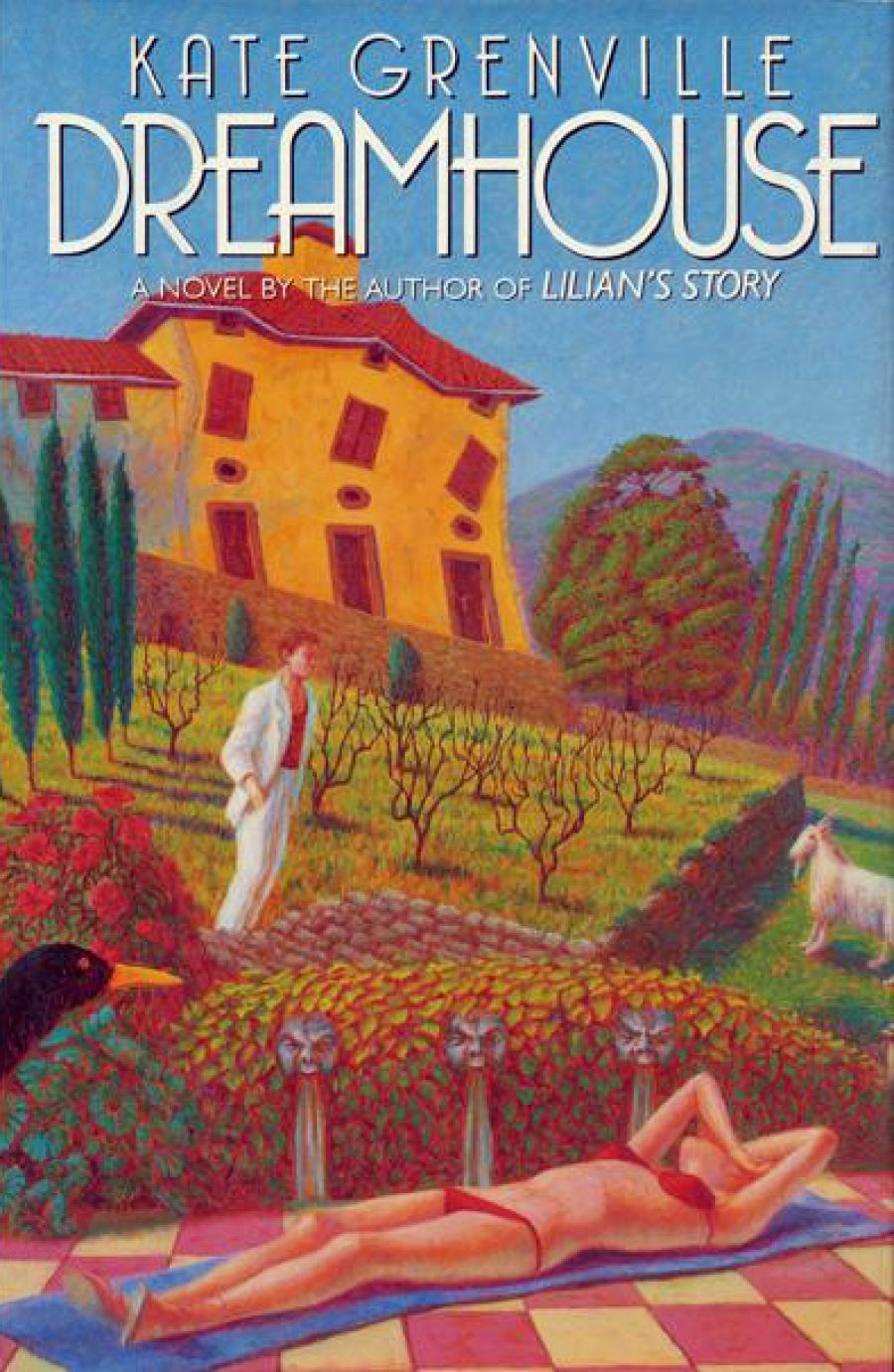

Dreamhouse, written before the wonderful Lilian’s Story (1984 Vogel winner), was the Vogel runner-up in 1983. Kate Grenville’s writing in this novel is clear-headed, strong, both witty and humorous, and above all lifts the imagination high. Dreamhouse wins my ‘Chortle, Gasp’ Prize for black comedy incorporating a design award for ‘best romantic fiction parody’ (it could have been called A Summer in Tuscany). It’s a darkly delightful book to read. Subversion of romantic expectations is immediate, ingenious, and horribly funny. Louise Dufrey is one half of an unlovely couple whose marriage looks perfect but is actually defunct.

- Book 1 Title: Dreamhouse

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, 170 pp, $19.95 hb

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/YXeYO

Reynold (Rennie to us) has been invited by Daniel, his old friend and mentor, to spend the summer in a Tuscan villa Daniel has spare so that he may complete – and Louise type – his doctoral dissertation. Sounds lovely; but as the young Lilian says, ‘books should have toilets in them’. So the landscape turns out to be repetitive and lonely, and the villa to be not marble, but practically derelict and full of mice. In the neighbouring villa, Daniel’s offspring Hugo and Viola (yes!) seem to be eccentric and singularly unneighbourly; the locals appear hostile and perverted. The very sunset is ‘full of long shreds of cloud and all drawn like hairs down a plughole’. Rennie and Louise are naturally taken aback by all this, and although they continue to call each other ‘darling’, and re-run their old jokes, the dialogue reads like a dead language. Moreover, in this most of crumbling old houses there is a kitchen, renovated with white tiles, dozens of gadgets, knives of all kinds, and a ‘huge marble table ... like a cadaver-slab’. We expect almost anything from this -but no conjugal renascence. This is the marriage morgue.

The title isn’t just satirical, though – it is the key to the way Grenville tells the story. Dreamhouse obeys the laws of dream/nightmare, or hall of mirrors, in which we are fascinated by a reality which presents most truly in its distorted form. Such distortion is characteristic of a narrative which sets out to show, not tell; to reflect the experience of people who have not the language to describe or interpret what they are going through. What Rennie and Louise go through – the summer of their marriage death – is intense and strange indeed.

When Louise first climbs through the broken window of the ‘mousehouse’, she enters a foreign world, ‘that smelled of mould and was dark, the unknown interior of a strange house’. The couple discover a room with

three narrow beds . . . each with a cover of clear plastic over the mattress. In one of them a family of mice had made a nest in the mattress among the kapok and the springs ... Four baby mice, like thick pink maggots, wormed slowly over each other . . . This happy family seemed to think it was invisible, safe under its plastic, and was not disturbed by the people bending over it.

Grenville’s images are generally easy to accept. This one gives a good idea of the resonances in Dreamhouse: we are not just strangely aware of things like fragility, imprisonment, vaguely impending violence; but of experience as a sort of conspiracy between the concrete and the possible. Louise is brought face to face with the fact that what she does isn’t quite what she feels. So the narrative, like the clear plastic mattress cover, exists as a tension between what seems to be happening, and what is, or might be happening. And the more grotesque and surprising the story becomes, the more familiar the reader becomes with Louise herself.

The lovely Louise, the ‘woman full of greed’, is in fact a ‘bearded lady’ in a dead marriage, a shag on a rock. Grenville has spoken of a conviction that we ‘actually have to take a step in the dark . . . into the void’ to rearrange the pattern of our lives: Louise enacts both the necessity and the sheer hardness of this. At times the tension is almost tangible:

In the dining room, where the whisper of the twenty jour clocks could be heard through the archway that led to the kitchen, I watched Daniel lay food and plates on the table. I saw that I would be clearly visible under the glass-topped table and would not be able to claw off my shoes with my toes, clench my fists in my lap, or scrawl obscenities on my knee. When he placed a huge pottery dish on the glass I made a mental note to refuse salad. The bowl could slip out of my hands and smash the table to glittering shards around our feet.

Now, Daniel cried. The piece de resistance!

Grenville’s tableaux are joyful to behold, over and over. They highlight the static, rehearsed quality life can have; they demonstrate the creative power of repressed emotion. And always the sidelong comedy, possible here because we have the scene not only from Louise’s viewpoint, but over her shoulder too. The possibility that she will drop a clanger and ruin Daniel’s charade is enticing – but it’s too early in the summer for Louise to be actively creative.

The novel streams with hints of unnatural carnal practices. It wouldn’t do to give too much away; but certainly Rennie ignores Louise sexually, apart from an occasional bit of sodomy before breakfast, so she is left to her own solitary sexual devices, including her curiosity about others. Domenico, the old rustic who brings their daily bread, leads a mysteriously vivid life in his barn where he presides over a goat, some hens, and the many chairs systematically pinched from house. Huge is a closet taxidermist; a series of enigmatic routines describes his relationship with his sister. There are memorable excursions – to the village festival, a superb gallery of weirdnesses; to a monastery, ‘famous’ for its frescoes and ‘notorious’ for its monks. The star of the frescoes is the devil, sporting red tights, and ‘so real that he looked as if he was about to turn and complain from his small rose-like mouth that he was freezing his balls off’ as Louise vivaciously observes to herself. Such moments remind us that Louise is quite human, and not just a receiving consciousness.

She is human enough in her need to fathom the secretiveness that surrounds her. She listens at walls, peeks into the barn, strains after the conversations of others, and conjectures endlessly. We share her obsession with the purposefulness of knives and sexual secrecy and suspect chastity, and yet relish the way Grenville continually postpones the ‘consummation’:

Hugo stepped from behind a bush, naked except for a straw hat, his penis erect. He was not at all embarrassed. Dark hair grew up thickly from his genitals and branched over his chest like seaweed and each nipple was ringed with dark hair. His teeth glittered on a smile, but the rest of his face was in shadow.

Louise. Well well ... I mistook you for my sister, he said. I hope I didn’t startle you.

In the shadow of his hat his teeth were very white as he walked past me and pushed into the bushes. He seemed to know exactly where he was going.

Faint harmonics of Lawrence and Twelfth Night – this writing has a wicked aplomb. Grenville’s special skill is the unexpected satisfaction of an expectation: ironic, comic, or grotesque. Just when we think we’ve got the hang of it, she brings us sharply up against a fresh possibility. And it’s a hard summer for Louise, learning the language of ‘living death’, and the need to translate herself into action.

Dreamhouse is a novel of our time. Grenville’s writing sits easily, for instance, with Drabble’s pathology of female inaction, Shirley Hazzard’s exploration of foreignness, Helen Garner’s infallible detailing; but what gives her an edge, even in a first novel, is her strength and control of overall structure. Like Bradbury or Christina Stead, Grenville is aware of a world in which freedom is often sacrificed as a matter of habit, usually in its own name; and she’s aware too that it’s boring to say so unless you’re good at handling large scale irony.

She is and produces two presiding ‘saints’, Malthus and Bartolomeo, who seem to have entered the novel almost by accident. Without spoiling the fun too much, it can be said that their overseership is unobtrusively, beautifully harmonious. Ambitious Rennie has chosen ‘Malthus and the Doctrine of Necessary Catastrophe’ as the subject of his dissertation: a tiny touch with resounding ironic reverberations. The great work is completed as part of the endgame, in Milan. And, on the very last day in Milan, we almost miss St Bartolomeo altogether. On the cathedral rooftop are many statues of saints, one swathed in black plastic. Louise is graphically preoccupied with the idea of falling off the roof; Rennie wonders in passing about the black plastic ‘maybe he didn’t do enough miracles’. Turning to the Oxford Dictionary of Saints, I was thoroughly pleased to discover St Bartholomew, martyred by flaying alive, the ‘patron saint of tanners and all who work at skins’, the saint with the emblem of a butcher’s knife. Chortle. Gasp.

Dreamhouse is a tour de force on its own terms. It both defines and (generally) overcomes the difficulties of sustaining a narrative which cannot depend on generating warm sympathy for the central character. Compulsive rather than attractive, it’s a novel in which we discover unexpected things about ourselves, and can still laugh at what we find. It would not seem surprising to come across Jane Eyre in some comer of it, archly reminding us that ‘it is in vain to say human beings ought to be satisfied with tranquility: they must have action; and they will make it if they cannot find it’.

Comments powered by CComment