- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

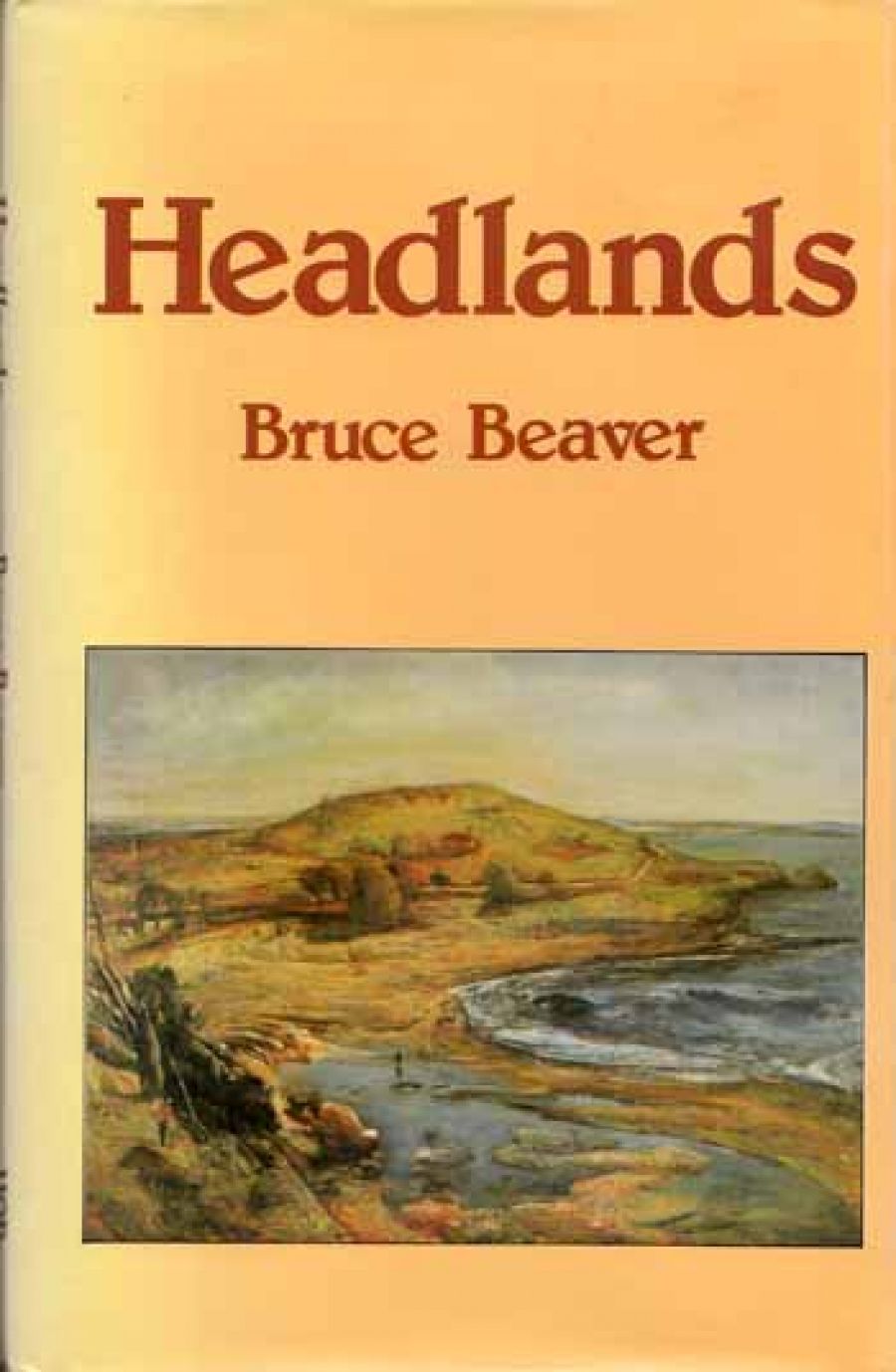

The jacket painting on Bruce Beaver’s highly wrought little book of prose poems is Lloyd Rees’ ‘The Coast near Klama’. It’s an elevated view of virgin green and dun coloured headland, the ochres rising through. Sea swirls into an oysterish bay. There is one distant figure looking down on another distant figure in a rock pool below. The sky, as with so many Rees skies, is egg-shelly yellow near the horizon, a glowing compliment to the taste we form and hold of earth.

- Book 1 Title: Headlands

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, 73 pp, $14.95 hb, 0 7022 1788 3

Beaver mentions, in the last of his metaphorically elevated, soaring and often plummeting to earth pieces, that many years ago a psychiatrist once looked at his therapeutic paintings and said, ‘Always houses and uninhabited landscapes – never any people, Mr Beaver’. Well, there is still some truth to that, insofar as Beaver’s focus is very much upon place, and also because he is to some extent engaging in passionate substitution: ‘I will become on my headland a numb profile, a petroglyph. Perhaps then, the other me who moves in streets and through rooms may learn not to hurt anybody. I am so tired of word-touching in anger those I love.’

But at the same time the human presence is very much there, both in the mobile registrations of the narrator (who in this case is an author indubitably and on the whole pleasurably alive), and the location of others, whether they be old loves in familiar physical settings, or acquaintances such as hospitable poets in their social habitats. Beaver is sardonic and basically affectionate – no inky squirts poets so often reserve for each other when they spy the rival rock pool. Here is Beaver in Melbourne:

crossing from breakfast with the white haired and stocky elder Queensland poet, sharing meals and readings with him, so gentle and yet so fierce, so stubbornly set in the Australian self-educated mould (my own) of poet prophet, so modestly yet self-assuredly sampling poached eggs and passing the marmalade he won our allegiances, and once unforgettably addressed a tree on the way back to our quarters: ‘They have intellectual lives of their own, I’m sure. Nobody can’t tell me they don’t live intensely or exultantly despite us – we plant them, even nurture them but they still manage to look down upon us’. Auden’s ‘vegetable egoism’ had somehow never been said.

This is cunning egoism on Beaver’s part, and embedded, as I say, in place. Bluefish Point. The Village. Sydney. Queenscliff. Abbotsford. Blue Mountains. Murrurundi. Berrima … Christchurch, Wellington, Pukerua Bay, Taupo and the Desert, Rotorua … Affections go up and out to the ‘light incarnate song and static dance of cicadas’, ‘to rock sand ragas’ and the ‘Buddha toenail of the newest moon’ – just to name a few of the unsayables to which some pieces point, while others descend to earthly, celebration of such things as steel pylons, ‘bubbly bitumen pavements, egg frying hot’, ‘giggling heat happy children’, ‘unwanted cups of tea and sugary biscuits’ – designations en passant, yet homely. It is as if Beaver is paramountly intent on his big wide mobile embrace, the better that the world can bear and be included. That last phrase is of course a rewording from Berryman, and there is the same high whirr in Beaver’s lines, though not, unfortunately, the same quality of focus upon the pinion that is about to fall out. A little too much tends to be willed. And there is always a lot of adjectival oil on the canvas, so that patinas upon the Sublime tend to wear thin, or are reborn out of vengeful swatches of the palette knife, usually the latter. I like Beaver best when he finds the middle which is (as is too often the case with Australian writers) when he looks back to childhood.

Here he is after thirty years away from Burrier:

‘Dawn came centuries later after travelling through vast spaces ringed by friendly stars that bummed and chimed like a farmhouse full of snores, up to and past the clock faced moon that struck the centuries like hours and down past the galaxies that added up to one great cowyard bails and dairy of the Milky Way until catching and holding on to the blue and drifting gown of the morning star we sailed back to our waking selves and heard my uncle’s boots stamping and crunching across the boards and onto the crisping dawn grass. He’d wake the adult women with unwanted cups of tea and sugary biscuits. They’d murmur thanks and sip a third of the boiling Billy blend, bite at and drop half the biscuit in the test of the tea then mumble to themselves and turn their sleep resuming eyes away from the just discernible open doorway.’

Such a citation, however, might seem to tame Beaver’s allusions (and allusiveness) more than it ought. The movement, as I say, of his pieces is crucial. Often perceptions are merely glimpsed – tunnellings of intuitions glimpsed, before sweeping on, or back to the old point. So it is in the Blue Mountains, where a mist kept closing the poet and his companions in. ‘We relapsed into an inward vision of scenic views tremendous and known’, Beaver writes; and the reader feels, ‘known yet still strangely unnamed’. I kept thinking of painters who work around and around, over and over what is physically before them, sometimes turning up with images that are trite, unworked, banal (Beaver’s New Zealand entries sometimes go too far this way), but working with an energy the circularity of which tremendously layers itself so that the object is, strangely, re-sensed. This book does not have the range, or indeed the penetrating lightness of touch of Beaver’s splendid As It Was, but it does have, in its swirling patternings, the requisite mystery energetically engaged.

Comments powered by CComment