- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Anthology

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The everlasting dance of sounds and feelings and colours, the taste and scent of life, comes to us in its most explicit form in words. Even when Proust’s famous Madeleine led him back through its scents and associations in search of a time that was lost, he followed its tracks through words that brought back the images of the past and tied them down into clear grammatical patterns of form and relationship. Because language teaches us how to think and feel and see it is always political. The speaker and the writer impose on us patterns which either reinforce or subvert established power. It is no accident that a failed conservative businessman and politician has been able to recover his fortunes by writing a political thriller, or that Mrs Thatcher has now engaged him on the task of selling her politics of destruction to a wary electorate. The words create the reality.

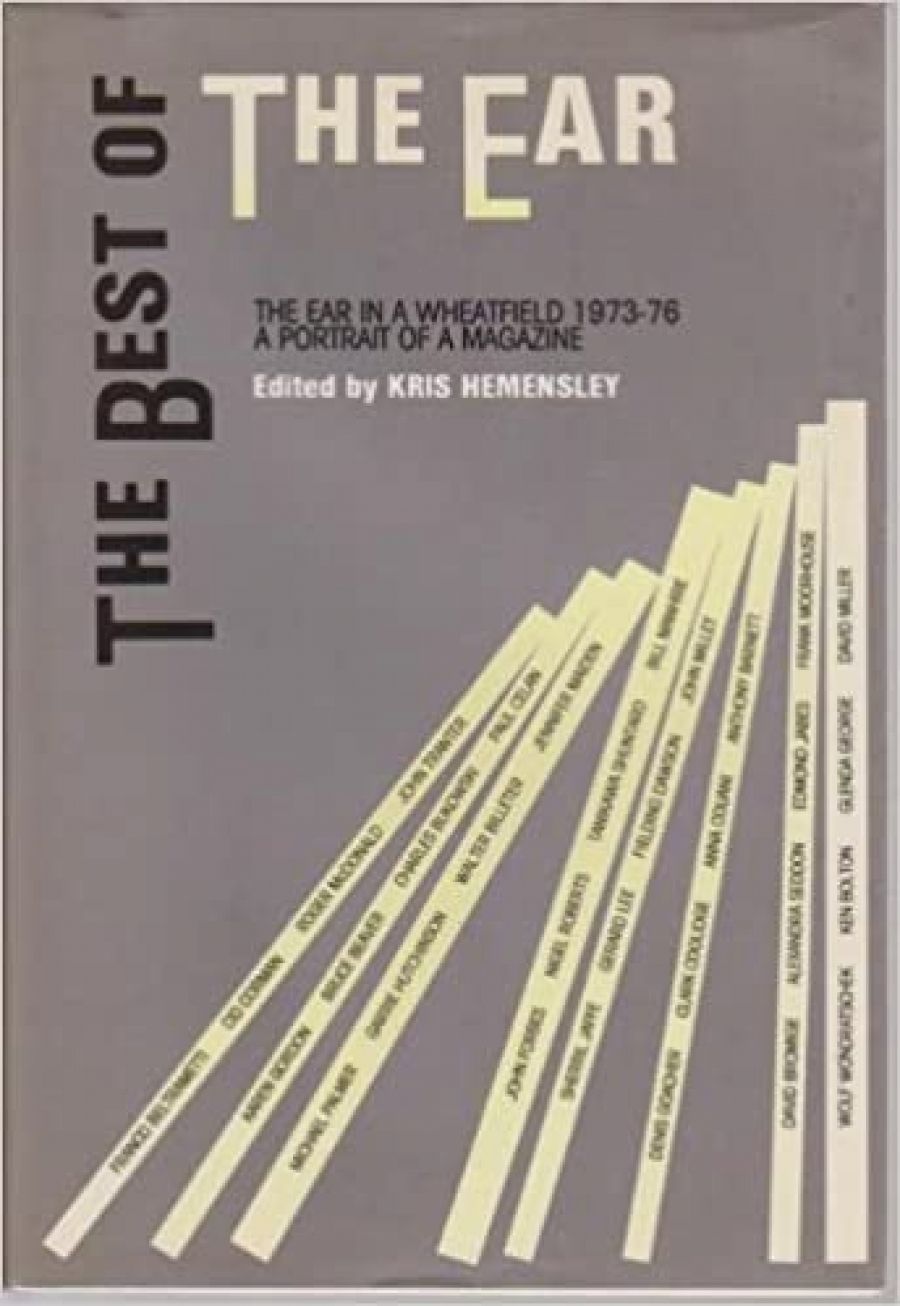

- Book 1 Title: The Ear in the Wheatfield

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Portrait of a Magazine

- Book 1 Biblio: Rigmarole Books, 255p., contributors’ index, $11. 95 pb 0 909229 29 5

Over the last couple of centuries politicians, philosophers and linguists have conspired, or at least coincided to convince us that there is no reality outside the words. There is a straight line from Kant, who says we cannot know anything outside ourselves, to Saussure, who says that the words we use to argue about our knowledge are themselves only a game of drawing distinctions in a nature which knows no boundaries, to the sociologists who say that even our own experience is constructed by society and the deconstructionists who say that the only thing we do know is our own words which have no meaning anyway. The Madhatter’s tea-party has grown until it embraces the whole world, but while the Duchess plays her games, the condemned lose real heads.

Since the resistance of the romantics to the reduction of humans to objects in the service of abstract systems, western writers have consciously sought to produce a literature of subversion. In the earlier nineteenth century, they championed the individual against the state, and found support for her in nature or love rather than in ordered society. Later, socialist realists championed the authenticity of working-class experience against the values and suppressions of orthodoxy, while conservatives took refuge in older structures of order, and nihilists distrusting all words and systems, in a code of blood and action which contained the seeds of fascism. In Australia, the realist opposition to the pieties of the fifties was succeeded by the activist writers of the sixties, who sought not merely to undermine the intellectual terrorism to destroy it.

Kris Hemensley’s magazine Our Glass (1968–69) provided both a training ground and a launching pad for many of these warriors of the word for whom Vietnam was the issue but personal freedom the end. After an interval in England, Hemensley continued his editorial work in Australia through the twenty issues of The Ear in the Wheatfield published between May 1973 and December 1976. This anthology contains a great part of the work published in this journal and thus constitutes an important historical record of the campaign.

The work from The Ear is less overtly political or public than much of the writing of the sixties. It is concerned with the politics of the person, the attempt to resist tradition, nationality, language itself, in order to make statements which remain open to the full complexity of existence. Thus verse, letters, translations, reviews, sketches and stories are mixed in a volume which seems to lack any cohesion other than the personalities of its contributors. Writers address each other by first names, with capitals, refer to themselves in the first person without a capital. Many of the contributions seem to have been ripped untimely from larger works in progress, and lack of the context which might direct the reader to their purpose. Hemensley seems to see this whole as a web in which the editor and his contributors follow the threads of their individual projects while establishing links between themselves which will open new possibilities to each other and their readers.

Hemensley has sought to bring together a community of writers who will be limited to no national boundaries. The work he publishes would be recognised as modernist or postmodernist, and internationalist. It is influenced by the California beats French symbolism, German surrealism, Japanese Noh plays and Zen Buddhism. The reader may be forgiven if at times he feels he is being invited to contemplate the sound of one hand clapping, and the perfection of workmanship and image which distinguishes Japanese poetry is too often lacking. The international community, moreover, is no more open than a national group, and is defined by its exclusions as much as its inclusions. Not only no traditionalists, not even an explorer of symbols and language like Les Murray, but few populists either – Pi O, Eric Beach and Shelton Lea are absent presumably because they share the faults Hemensley attributes to Lea: ‘The rage outrages only itself (the poem) the violence is stuck upon the page (with or without capital letters) and the impotence the poet claims is all that is left to him after writing the poem is sad to say deposited in the poem … Feeling of its own matters as little as that other abomination – sincerity’. Which seems as meaningless, and as mystifying, as saying that the language fails to leap off the page. Hemensley’s choice as editor is determined by that sound, old-fashioned principle of personal taste.

And the anthology does contain a great deal of verse, and a rather small amount of prose: which does leap off the page, surprising the reader with an image or a rhythm which does not merely create a mystery but suggests a new way of comprehending experience. The speaker in Robert Harris’s ‘Efsthatious’ takes the listener on a sad pilgrimage through his past in which he recalls:

Catastrophe,

Insurgencies,

Trouble clearly writ upon

The moving tendon and bone, I’ve come

To put these things behind me.

These lines become a chorus to a poem which opens from the personal to the public, suggests the betrayals and losses forced upon the speaker, but also records moments of triumph when he recalls:

The gourds and dancing

Drunks and romancing

Trysts in outbuildings, festivals half and half

Arranged for the old gods pleasure

And to frighten the shit out of the fatuous priests

The traditional images me shocked into a new statement by the colloquial. The whole poem is written in a free metre which does not tie it down to the containment of the precise, yet still achieves a formality which enables us to believe that the speaker has by the end achieved the strength ‘To dance alone now’.

A similar strength is shown by writers as various as John Tranter, Cyd Corman, Bruce Beaver, Robert Kenny and Ken Bolton. Frank Moorhouse provides the only piece of really savage humour. Some writers, like Phillip Hammial, seem only to be playing two-finger exercises, rather than trusting the language, in the knowledge that ‘To write is to go in search of chance’, not the chance itself. And, in a book so devoted to a future free of the past, it is surprising to find at least two references to Ern Malley and his other ego Max Harris. One of them, Laurie Duggan’s unfunny anagram, is quite gratuitously offensive.

Yet, in a book of this kind the whole is more important than’ the parts. The writers all, in various ways, would seem to share Clive Faust’s view that:

In such a bare age as ours, the truth, though terrible, is clean. The worlds of Chaucer, Homer and Tolstoy were conventionally realised ones – even if the men in them shifted between realizations, incorrigibly. We are now in the same ferry as these chaotic Americans: we have no fixities to shift among …

Ultimately the variety – of place, for instance, of event, of impression is deceptive: Also the enormous amount to be learnt from them, deceptive – because it is all the one thing. And the one thing is terrible, because it is unclear whether it is not ourselves.

In this terrible world, the writers try to create first themselves, whether, like Finola Moorhead, they try to go behind language to recreate a primeval and prelinguistic unity of form; or, like Walter Billeter, they seek a self, a person, free from the past in history or memory; or, like Edmond Jabes (in translation), they explore the inner world of terror; or, like Robert Kenny, they find a poem in its own collapse, where knowledge ‘weaves itself down a tunnel of endless consequence’.

The question the book does not address is whether this hermetic world of language is not itself just another fiction, the product of late urban industrial society. In its international aspirations, the collection ignores the writing from Africa, India, South America, even central Europe, which knows both the deceit of language and the concrete reality of experience. The ear in their wheatfields is not an aperture to an inner world, but a promise of food.

Comments powered by CComment