- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Diaries

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘We assume, of course, that we are masters and not servants of facts,’ observes T.S. Eliot in an early essay, ‘and that we know that the discovery of Shakespeare’s laundry bills would not be of much use to us’. The sentence continues, still flickering between amusement and seriousness, futility of the research which has discovered them, in the possibility that some genius will appear who knows of a use to which to put them’. If he had lived a decade or so longer, Eliot may have smiled to hear of the furore which attended the publication of Nietzsche’s unpublished manuscripts, including his laundry bills. And while he may not have been entirely amused by Jacques Derrida’s essay, Éperons, partly prompted by this publication, Eliot would doubtless have agreed with one of the theoretical points that was made: it is impossible to tell for sure which of an author’s writings do not belong to his or her oeuvre.

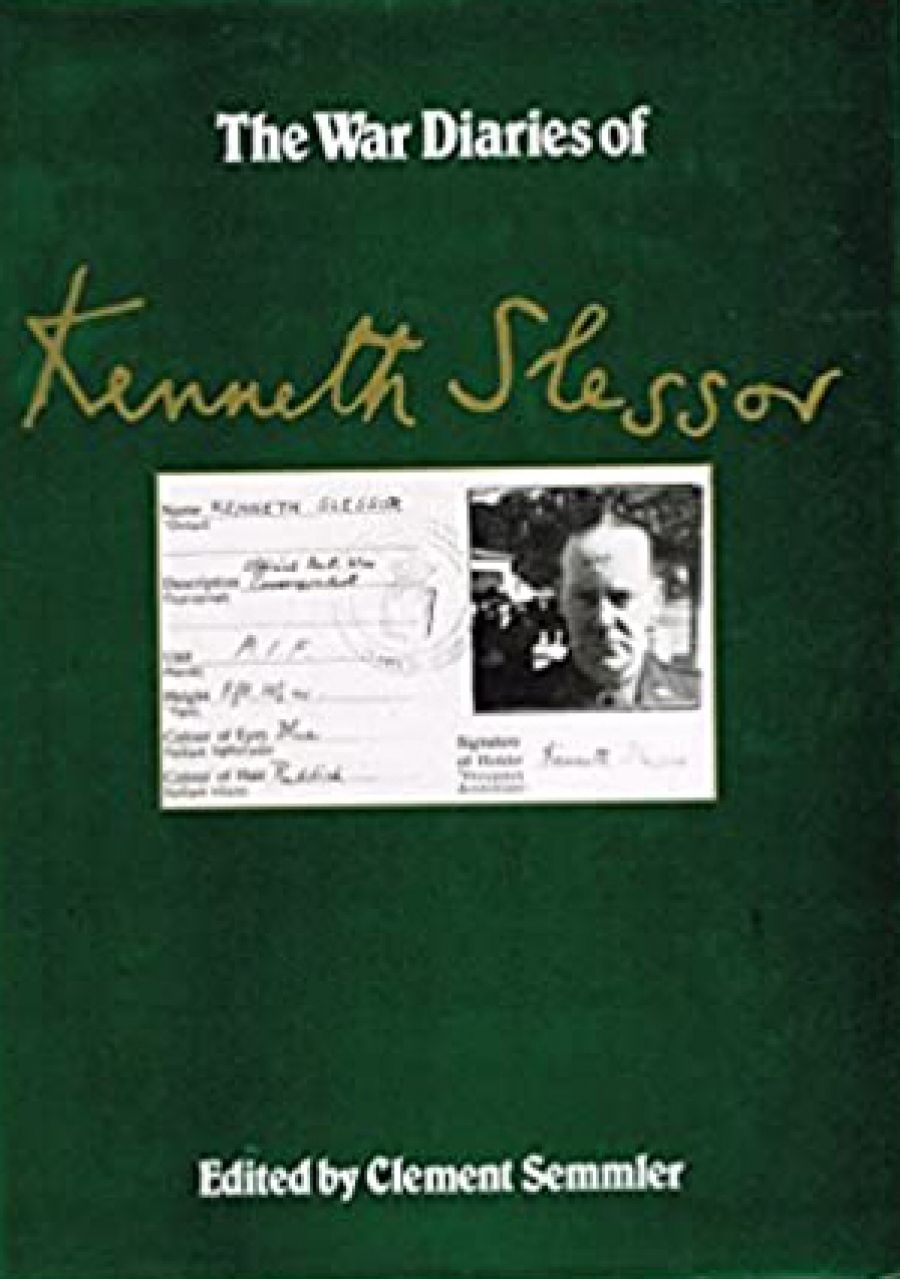

- Book 1 Title: The War Diaries of Kenneth Slessor

- Book 1 Subtitle: Official Australian correspondent 1940–1944

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, 623 pp, $40 hb

Putting theoretical points aside for one moment, let’s take a look at this thick volume of Kenneth Slessor’s war diaries. Unless I’ve slipped up, there’s no mention of any laundry notes, although one does hear a good deal about hotel and dinner bills. One also hears about those with whom Slessor dined, what was eaten and what was drunk; daily pleasures and frustrations are noted; different landscapes are observed and remarked upon, sometimes vividly, sometimes not. There is a distant fury of battle which, on occasion, comes rather closer and rather more furious; there are reflections upon the absurdity of English class-consciousness and the pomposity of Generals; and, of course, one hears a good deal about particular campaigns, especially the debacle over Greece. Despite all this raw material, though, these diaries do not transcend the tedium which is part and parcel of most people’s diaries, whether in peace or war. As diarist Slessor has neither the insatiable curiosity of a Pepys nor the emotional intensity of a Swift. If this book has any interest whatsoever it is only for two reasons: these are the diaries of the official war correspondent and, more particularly, they happen to be written by one of the country’s finest poets.

I suppose these two reasons are sufficient to warrant the book’s appearance. In fact, I suspect that the second reason is sufficient in itself; for as long as there’s substantial scholarly interest in Slessor, there will be commercial interest in anything that’s produced bearing his signature. Without the Collected Poems there would be no such thing as ‘Kenneth Slessor’; but because we do have them, we also have the prose of Bread and Wine which, by itself, would not attract much critical attention. Indeed, because of Slessor’s poems, there can be no end to what could be of interest: drafts of poems, letters, notebooks, journalism, examination scripts, marginal notes in his or other people’s books, even laundry bills, are contenders. After all, no one can say that anything by Slessor has absolutely no significance for reading his poems: there’s always the thought of Eliot’s future genius to keep us in our place.

At the level of theory, then, there is very considerable justification for collecting and perhaps publishing anything found to have Slessor’s signature. But there are two further considerations which are relevant, both generally and with regard to this particular book. In the first place, there is the question of the reader’s interest. I very much doubt that anyone, not even Slessor’ s greatest admirer, could possibly find these diaries of literary value. War historians may find useful material here, and memories might be revived by soldiers who served in Greece, Crete, Syria, El Alamein or New Guinea. Literary critics, however, can only be disappointed, for Slessor offers no revelations of his habits of poetic composition and discloses no theories of art. True, there are a handful of striking images (‘the air was full of searchlights Jocking their fingers’) but these are few and far between. More generally, the entries are too staccato to sustain a continuous reading, too banal to be dipped into at random; and by the time one gets to the end one realises that all the interesting details and lyrical passages have already been encountered in Semmler’s introduction. It is a very thorough introduction, I should add, supplying us with a biographical note on Slessor and documenting everything one could possibly want to know about Slessor’s appointment and duties as official war correspondent with the A.I.F.

In the second place, there’s the question of the morality of publishing a person’s private writings. It’s true that Slessor, as official war correspondent, was obliged to keep diaries for official histories to be written, if requested, after the war. So, these particular diaries are more or less fair game. All the same, though, there’s a good deal of personal detail here which is really no one’s business but Slessor’s and which he may well have wanted excised had the diaries been edited in his lifetime. And what makes matters worse is a curious moment of editorial coyness. Perhaps for reasons of partial indecipherability, perhaps for reasons of delicacy, Semmler has omitted several entries in Slessor’s diaries for March and April of 1942. There is a note informing us that the entries are in Slessor’s idiosyncratic shorthand and pertain to an affair which his wife, Noela, was having with the journalist and author John Hetherington. I can’t imagine anything less interesting than what these details actually consist in, but one thing is certain: if Slessor’s poems continue to rise in critical esteem, as I hope they will, it’s possible there will be a second, unexpurgated version of these diaries on the market.

The message is plain. If you are a writer who feels at all touchy about having your official or private papers published after your death, destroy them all now. At the moment, the arguments from interest and from morality carry no weight when compared with the arguments from scholarship and theory. If you are a reader interested in war diaries, you might find Jean-Paul Sartre’s more compelling; and if you are interested in Slessor, you can’t do better than reread his poems.

Comments powered by CComment