- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Not ‘Holmes the Man’

- Article Subtitle: One man’s way of looking at the world

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Like many students of Australian film, I became aware of Cecil Holmes’s work through the viewing of a scratched print of Three in One in a lecture hall in one of our tertiary institutions, many years after it had failed to gain general release within Australia and killed off the dream of an indigenous film industry, yet again. A brave and naïve film, it was clearly well-made, stylish, and addressed a local audience without condescension or parochialism. Three in One was an early hint of what an Australian cinema might look like, and is now held to be one of the landmarks in the history of Australian film. To those who see the film now, though, its maker must seem to have suffered the same fate as its optimistically named production company, New Dawn Films. There is some satisfaction, then, in reading One Man’s Way to see what did happen to a substantial talent squandered by an insecure and conservative Australian film industry.

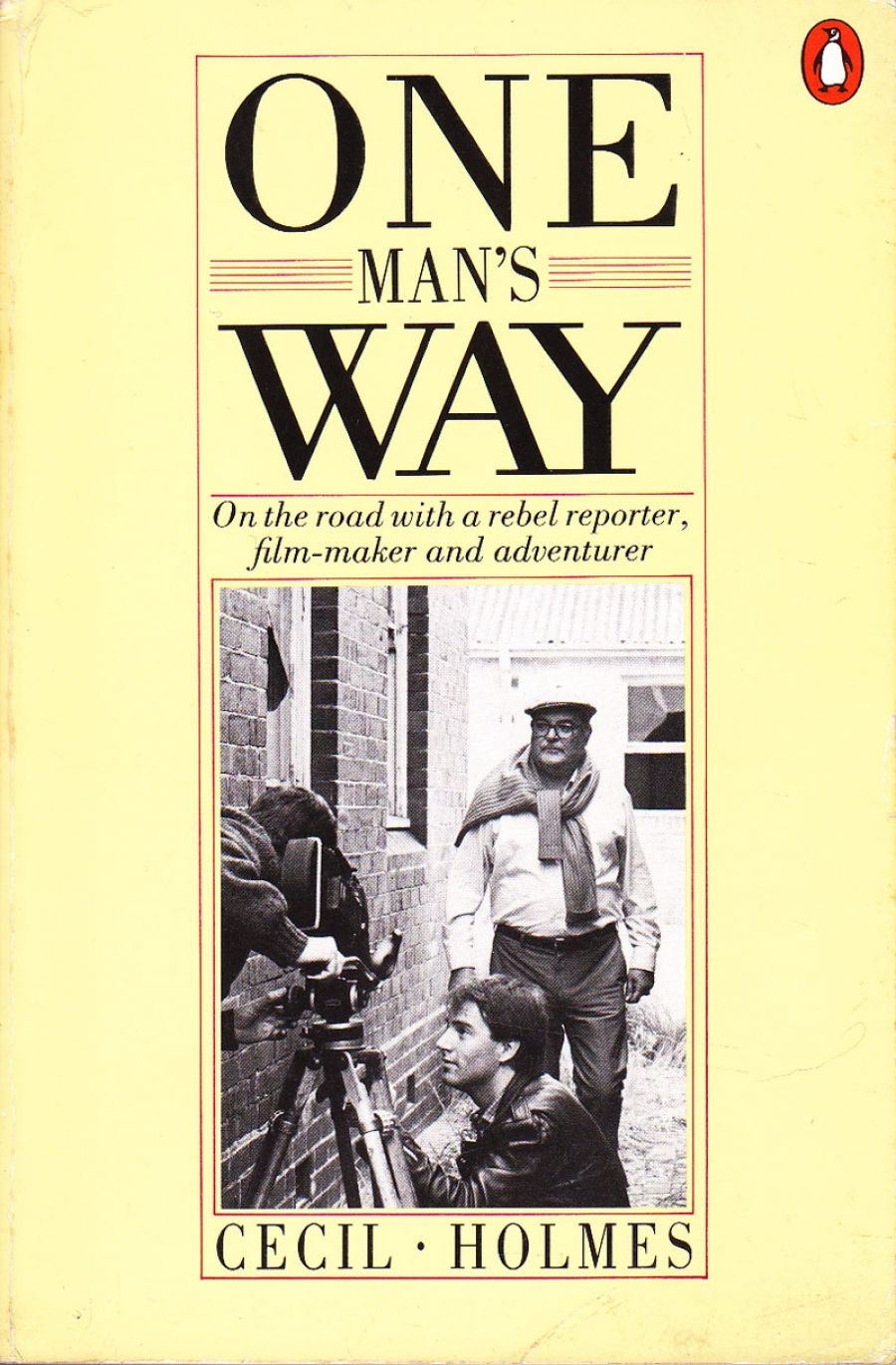

- Book 1 Title: One Man’s Way

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, $9.95 pb, 256 pp

It is not a typical autobiography. ‘Holmes than man’, as Sixty Minutes might call him if they were interested in humane and unrepentant Australian communists, does not occupy much of the text. It is the kind of self-effacing account of experience that marks some of the finest essayists. Holmes assumes, for the most part, that his experiences are not of interest because they are his, but because he was fortunate enough to have them happen to him. As experiences, they have the potential to be both representative and illuminating. But they do not include discussions of his marriages, his children, his personal crises, or his dealings with rejection, discrimination, and what amounts to blacklisting in the Australian media. This may cause frustration for readers who want that kind of information – and certainly some reviewers have expressed disappointment at the absence of this perspective.

The book is, however, not so much about the man as about politics. In Holmes’ essays we have a thought-provoking account of what happens to a man whose life is dominated and determined by his political beliefs in a country which is suspicious of politics, sceptical about ideas, and downright afraid of ideology. Holmes is typed by his publishers as a ‘rebel reporter’; in contrast, the man who emerges from the contents is engagingly ordinary. He is a victim of the histories he writes, not their agent or their author. The trips around the globe are not exercises in tourism or consumption, but reflections on politics – on the systems under which people live and those systems’ failure to provide freedom and equality. His last essay underlines this concern, the ‘familiar dilemma of how to solve social/economic problems, yet safeguard, even develop, freedoms that have been so hard won over the centuries’.

There are other reasons for reading the book. Those sections which deal with the film industry in Australia – and they are surprisingly few – reveal how little has changed. The struggle for backing, the attempts to attract overseas sales, to arrange local exhibition, and to make films that actually speak for the Australian culture as well as to foreign cultures, are documented in Holmes’ book and would be recognised by contemporary film-makers. Holmes’ sense of history, a benefit of his Marxism, enables his views of other cultures to take in both the immediate and the personal as well as the structural determinants of the lives on offer to their people. In some cases, a counterpart is provided by the juxtaposition of two views – displaced in time – of the same phenomenon. The piece on Rum Jungle, for instance, pairs a celebratory view of industry and progress with a critique of the ‘bland and soothing’ nature of the former. The method of providing perspectives on perspectives is used frequently. Holmes as a journalist has much in common with Holmes the film-maker. The reporting is so effective because it is so visual; and while it has a point of view it is in no way didactic or restricting. Writing prose, Holmes sees in pictures, arranges them in montage, and refuses to deliver the final pithy line (mostly) that will ‘fix’ the meaning for his readers. As a result, the pieces have a resonance and thoughtfulness that becomes one of the real pleasures of the book.

I awaited the arrival of this book with some eagerness and am not disappointed. Cecil Holmes emerges as an observer and writer who can do more with his experiences than most of us. Despite the book concluding with his return home – to work on a film version of Conrad’s ‘The Planter of Malata’ – it still provokes the reader to regret the wasteful facility with which the Australian media has repeatedly dispensed with than man’s services. That Holmes’ account of his own dispensability is without bitterness or resentment is a credit to the man; that one could forgive it if it did surface is an indictment of the society and the industries he should have served more often.

Comments powered by CComment