- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Architecture

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Saltbush Building

- Article Subtitle: Towards an Australian architecture

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

He that hath no relish for the grandure [sic] and joy of building’, wrote Roger North in 1698, ‘is a stupid ox.’ Unfortunately, despite the considerable progress made over the last thirty years, such oxen abound in Australia. One has but to think of the destruction of Brisbane’s Bellevue Hotel, or of Townsville’s Buchanan’s, its balconies the most artfully cast-iron laden in the country: fire had destroyed the rear of the building, justification enough for the council to move against the façade. Not even appearance on a postage stamp was enough to save it. But it is not only in Queensland that we see the depredations of these Captain Midnights: Melbourne recently saw the Toorak Methodist Church similarly attacked, to the point where it was deliberately placed beyond repair. Developers and the imperatives of capitalism still effortlessly outpace both half-hearted conservation measures and the degree of public awareness necessary to make such sanctions work.

- Book 1 Title: The History and Design of the Australian House

- Book 1 Biblio: OUP, 328 p., illus., biblio., index., $50.00

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

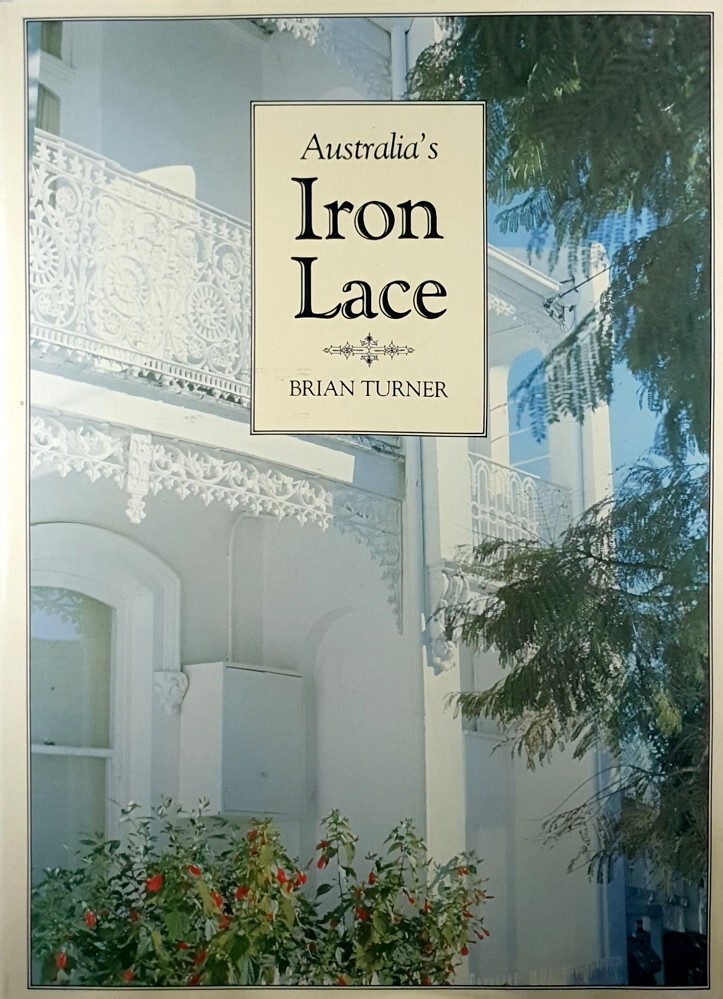

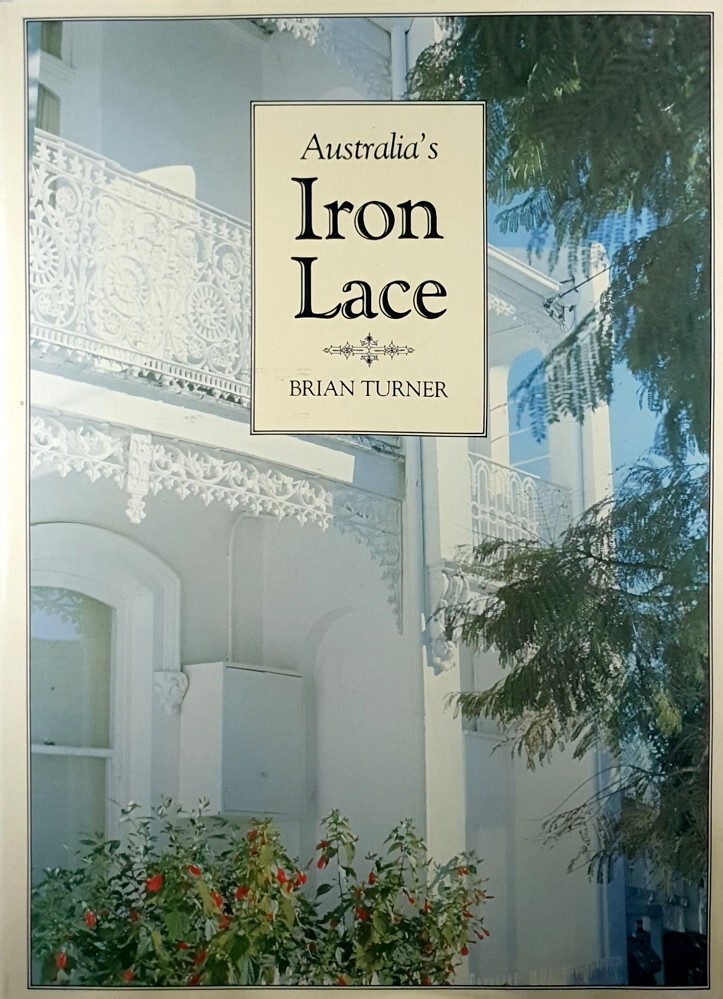

- Book 2 Title: Australia’s Iron Lace

- Book 2 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, 192 p., illus., biblio., index, $39.95

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 3 Title: Leaves of Iron: Glen Murcutt, Pioneer of an Australian Architectural Form

- Book 3 Biblio: Law Book Company, illus., biblio., index, 148 p., $37.50 hb

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

The present three books all assist with the consciousness-raising still required in heritage and environmental matters. The History and Design of the Australian House, compiled by Robert Irving, as one would expect of a tome from Oxford by various hands, is analytical and slightly dry; less expected are the excellent illustrations and the way that the book makes a valiant effort to say as much about the twentieth century as it does about the nineteenth. Philip Drew’s Leaves of Iron, on the other hand, is a vigorous and erudite polemic arguing that, in Glen Murcutt, the country has produced its first real architect. Brian Turner’s book, Australia’s Iron Lace, is also the work of an enthusiast: it offers many useful insights into cast-iron and its culture, and the author’s affection of the form and its whimsical ways is evident throughout.

The question of whether a distinctively Australian style of architecture has emerged over the past two hundred years – or has been glimpsed at odd moments – is clearly a preoccupation of the present writers, whether addressed by them directly or allowed to remain embedded in the text. If one were being cynical, it could be said that the most conspicuous Australian style evident is the compulsion the country seems to feel every forty years to engage with contemporary architecture, as if to see who will win. Butterfield, Griffin, Utzon: all accepted important commissions here, and each retired defeated. (One of Butterfield’s last letters concerning the construction of St Paul’s Cathedral concludes with the line: ‘Am sorry to have heard of Melbourne.’) Certainly, we produced the terraced house in great numbers, but it is not unknown elsewhere, even to the lace, while the veranda was a stock item of tropical colonial architecture and may have originated in Portugal. Ray Sumner, in the Oxford volume, argues energetically if not entirely convincingly that even the Queensland style, with the veranda included in the roofline while the whole house sits on stumps, is far from unique. (Perhaps it’s the lack of style, then – the exposed timber frames which Ms Sumner refers to.) The Australian element has often been merely gestural: flora and fauna cast in iron panels, stranded on Federation gable tops, or put pertly in place in Art Deco motifs. New techniques there have been, such as light timber framing, cavity walls and brick veneer, but a new architecture, closely attuned to Australian conditions, has been slow to develop. Conservative values meant that the harbingers of new styles stood out like shags on a rock, unheeded if not unnoticed. When Hardy Wilson built his colonial Georgian house ‘Purulia’, its clear lines were the despair of his North Shore neighbours, who thought it would lower property values. Instead, it became a prototype. But, as Philip Drew argues, in his concern with style – even so classical a one as colonial Georgian – Hardy Wilson took the wrong turning. Style as such has to be abandoned in Australia, for, derived from abroad, it is ‘an obstacle and not the means’, impeding the architect from responding fully to the challenges and opportunities presented by natural conditions in Australia. He must deconstruct, in order to invent and build anew.

Drew, who speaks of Murcutt’s work as ‘restoring our national self-respect’, is highly conscious of the derivative nature of Australian architecture. For a long time it could scarcely have been otherwise, and the influence was not always baleful. The Tasmanian architect John Lee Archer worked with Rennie, the engineer of Waterloo Bridge, while Greenway had worked for the famous John Nash, the architect of Regent’s Park. Pugin and Gilbert Scott undertook projects in Australia; an Adelaide house was furnished by William Morris, working from the plans. English architects were sometimes used to embellish the local, as when the editor of Building News was asked, by the commissioning Fairfaxes, to clothe a local architect’s design in convincing Queen Annery.

As this last example suggests, such derivativeness went on for far too long. Right to the end of the century, most architects of note had been born in Britain and had even practised there. The first local qualification, a diploma from Sydney Technical College, was not established till 1896. Its necessity was underlined by the way Robin Dods, a Brisbane architect, had already returned home to practise after having gone to England and known such people as Mackintosh and Norman Shaw, leading architects of the day. (Dods was to dramatise this return by his imaginative refinement of the vernacular Queensland house.) Thereafter Australian architects increasingly went abroad to examine trends for themselves. The temptation to remain there diminished, as many had established themselves in practices already.

Claims have often been advanced for the uniquely Australian character of cast-iron lace, and Brian Turner, in his generally careful account of the subject, asserts as much here. Apart from New Orleans, cast-iron of a kind familiar to Australian eyes turns up everywhere. Many have seen the green balcony on the corner adjacent to the British Museum. E. Graeme Robertson was entranced by a bandstand he found in Bangkok; I once came across a house in Swellendam, South Africa, which would have been entirely at home in Carlton. In short, cast-iron was an international currency. (Turner himself shows how even some French patterns made their way to Sydney.) What probably makes it ubiquitous in Australia was that, unlike almost anywhere else, white settlement proceeded hand in hand with the progress of the industrial revolution. As a matter of course townships were established with foundaries, many of which turned their attention to making cast-iron panels as well as farm machinery. One might say, too, that cultural lag helped to keep alive the Regency idea of a balcony: witness the painted stripes of their roofs, a relic of earlier fashionable awnings. This legacy combined with the colonial veranda, a defence in the face of an ‘extreme’ climate, to make the cast-iron façade a fixture in much nineteenth century Australian building. In the towns, probably the majority of houses in 1890 were terraces, and together with those which were not, the degree of cast-iron ornamentation was such that Melbourne probably had more iron lace than any other city in the world. As Turner shows, ‘cast-iron impudence’ was linked with a colonial desire for display, a sign of success, which was why that phrase came so readily to hand to its first detractors. Indeed, the particular value of Turner’s book – bearing in mind that we must modify ‘uniquely’ Australian to ‘peculiarly’ – is that he traces the decline of the fashion, pointing to a last pub built in the style in Dimboola in 1924, and includes accounts from old-timers which help to account for it. Talking easily to a former wool-classer, they told him that on country pubs the problem was not so much the iron as the wood beneath it, which would rot, loosening the panels and making them dangerous. Force of fashion dictated removal rather than renovation. But then as late as the sixties, some will remember, inner suburban real estate agents still referred to ‘brick balcony residences’: the cast-iron might as well have been invisible.

Comments powered by CComment