- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Wild About the Man

- Article Subtitle: Much sense, much feeling

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘The Man of Slow Feeling’ is the title story of a selection of Michael Wilding’s short stories published between 1972 and 1985.

These stories vary widely in setting, content, character, tone, but Wilding’s voice is consistent. By ‘voice’ I mean that if I was given an unidentified story in an envelope I’d be able to tell if it was Wilding’s before I was halfway through. It would be a plain, sealed, brown-paper envelope, of course.

The voice I hear is that of the writer as condemned observer. It records experience, it records itself in the midst of experience, it records itself recording. The title story is apt: the man of slow feeling is broken in the attempt to record and experience at the same time. The voice telling the stories is so distinctive that very soon I gave up trying to keep writer and writing separate in my mind. Whether they are first person narratives or not, the stories are intensely personal. They always seem to reveal what the writer chooses to expose of himself.

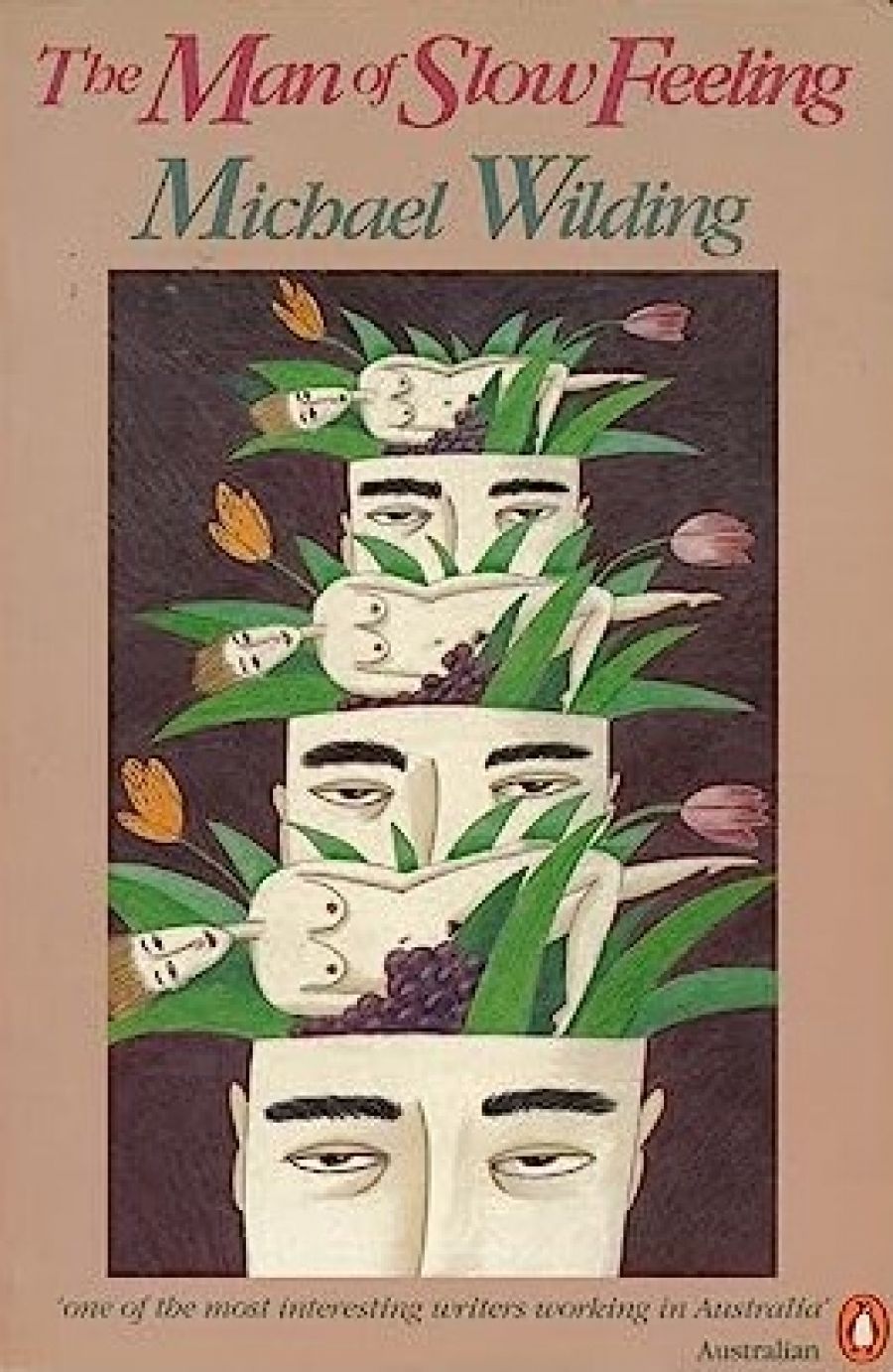

- Book 1 Title: The Man of Slow Feeling

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin Books, 303 pp, $8.95 pb

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

There is a familiar ring to this quality of voice, and Wilding identifies it to my satisfaction when he says of one of his distrait characters: ‘Probably he had read Camus and Sartre at too impressionable an age, when they had been issued in Penguins during his adolescence.’

Sartre, Camus, you heartbreak old existentialists! The ghost of the Outsider walks these stories, and it is quite at home in the junk-tilted, slippery slope to apocalypse-when? eighties.

So there’s a sense of estrangement, with consequent misanthropy, running through all the stories. But they are by no means flat, nor is the storyteller disinterested. Some are impelled by anger, more have sexual dynamos.

This description of what I’ve called this writer’s voice is necessary to explain why I think ‘sexism’ is too blunt an instrument to use here, although that was the word that sprang to mind. Wilding’s protagonists, usually male, are so self-absorbed that anyone else is just another external event, an occasion for experience, and women rouse sexual responses, every time it seems. So women are often written about with chilling objectivity, as instruments for sexual experience.

Women are alien of nature to the estranged male observer of so many of the stories. They bond together, excluding him; they toy with him, seduce him, and dump him; they lead him into worse temptations than just those of the flesh; they are hysterical or calm, but always remote. They are dangerous, and dangerously fascinating because they are a key to the release of sexual energy, which is essential for living.

On a more intimate, almost domestic note, a woman is seen as a means to salvation in at least one story, and in another, sympathetic and sensual, the world is seen through a woman’s eyes. It is a different planet from that inhabited by the male characters.

If the sexes were reversed and the men were doing all the toying, seducing, dumping, and promising (one way or another) to take her away from all that, it would be easier to yell ‘Sexist!’ Besides, the male characters are at least as flawed as the females, they often collude in their own undoing, and they don’t have as much fun.

The most interesting stories were the vertiginous ones about writing itself, that process that goes on and on whether there’s a pen in your hand or not. Although ‘The Man of Slow Feeling’ is dated 1975 it remains the right title for this selection. It is a fable that illustrates the condemned observer-recorder’s dilemma with elegance and pathos. ‘The Words She Types’ is elegant too, but more a piece of machinery, as this kind of story often is. More moving (not tears: teeth-grinding) were the most personal stories about writing, the cris de coeur from the depths of the dilemma, ‘Writing Again After a While’ and ‘Their Minds Keep on Working’. All these stories are from the 1975 collection ‘The West Midland Underground’.

Most of the stories in this volume carry an erotic charge, but some from ‘The Phallic Forest’, 1978, positively blaze with it. Sexuality is celebrated here and it’s powerful stuff. It can sicken or sustain, it gives the screaming heebies when its impulse is frustrated, it can be transmuted by writer’s sleight-of-hand into something else, for instance comic despair and horror comic in two stories about nights spent in other people’s houses.

In this section is the magnificently pornographic parody of an episode from Jane Austen. This time it’s the real Emma, vain, snooty, smug, and silly enough to keep her dignity, as we suspected she would, always. Each of these stories sounds different from all the rest, and it seemed to me that there were other parodic echoes: another Alice in another Wonderland; a story that J.G. Ballard might have written; a character who said he felt like Jimmy Porter just as I began to think he was another Jimmy Porter; a Poe-like tale of something nasty under the bed, with a female character to match old man Steptoe. And others.

It is satisfying to read work written across such a span of years. The later stories are no more developed or polished or closer to perfection than those written a dozen years earlier; rather it is possible to see Wilding’s progress towards his current preoccupations and clarity of intention. The early stories are relatively neat and well-closed: the latest acknowledge the infinitely amorphous quality of experience and its recording in story.

It’s as if Wilding has hit his stride in the stories from the final collection. (Reading the Signs, 1985). Life – of the street, in the mind – merges with story. He puts it better than I can paraphrase it in ‘Yet Once Mote’:

Everywhere is redolent with stories. They leap from windows and beckon from gratings. These are the bars, those the alleys. Stories hang around us making the air thick to move through … Stories settle on us like pigeons on a national memorial.

I haven’t said how sentence by sentence l liked reading this book. I haven’t commented on the satirical bits, or grizzled from some more alleviating irony. But the cover of the book (Penguin, no doubt issued during someone’s impressionable adolescence) is so good that I’ll spend the last words on it. The illustration by Noela Hills is a metaphor for the contents, and also

Comments powered by CComment