- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Short Stories

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There is a lot of work still to be done on the place of the yarn in our culture. Has its pre-eminence to do with the roving outback life, with traditions of taciturnity, with an inability to cope with the size of our land? Or has it more to do with the rapid urbanisation of this country and a need to celebrate and protect myths, an abiding sense of nostalgia? Or are there more pragmatic, economic reasons – the dearth of publishing houses, the lack of a landed gentry, the impossibility of survival as a full-time writer? Whatever the cause – and speculation is interesting – there can be little argument about the fact that the yarn has a central place in our literature, whether firmly embedded in a longer novel as in Such is Life and The Wort Papers, or staring at us from literary magazines or collections of short stories.

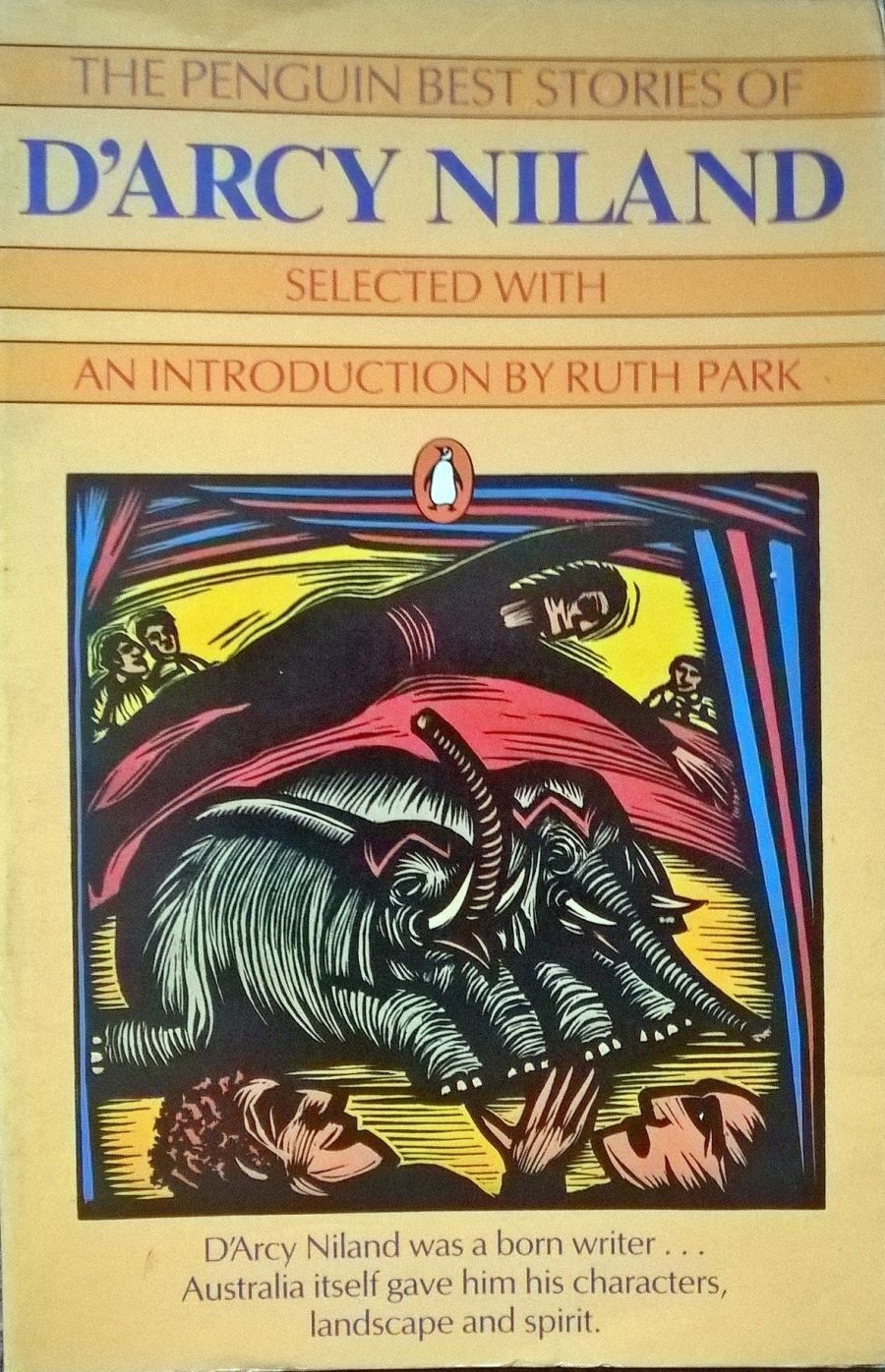

- Book 1 Title: The Penguin Best Stories Of D’Arcy Niland

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, 205 pp, $9.95 pb

The yarn is protected from too much destructive ferreting by those literary critics who dislike writers but love theoretical constructs. It is an elusive form dodging about through the tone and voice of the narrator who is now a naïve bystander, at other times a central participant and, on occasion, the detached God-artist, paring the fingernails.

Ruth Park, who is no mean storyteller herself, has seized this opportunity to select, from her late husband’s work, the yarns that best represent his range and style. She maintains that D’Arcy’s love of the language ‘must have been genetic and filial’:

About it he once said ‘Other people had warm clothing and the best cuts of meat, but we had the words’. This was true. His family’s day-to-day conversation was straight out of Behan and Myles na Coppaleen. In more tumultuous moments it became pure Synge.

D’Arcy was Irish, certainly, by temperament and tradition, but he was also thoroughly Australian, a man who took his experience first-hand as he wandered this country recording his observations, meeting the characters, working the odd jobs. Ruth Park insisted that D’Arcy was strongly influenced by the classic European short story writers – Tolstoy, Maupassant – and spent a good deal of time crafting the shape of his stories, ‘Because I’d suspected it somehow, the shape of the European stories. A strong shape, like a tree. Not at all like Henry Lawson or the others.’

Reading this selection gives proof to Ruth Park’s claim. Each story is carefully crafted, the voice in control of its own telling, classical examples of beginning, middle and end. Here are but some of the opening lines:

There is a name without a place. That’s what they say and they’ve been saying it/or a long time. But it’s a place to me, a belonging, and that’s why I came and that’s why I’m here.

The directness, the boldness of the voice, its unselfconscious address to the reader, is a challenge that can’t be resisted. We must go on, we must meet this person and find out about her (yes, it’s a her) place.

Another story opens even more bluntly:

This was the woman I took for mate and I wanted no other.

I met her in Tintinara, the daughter of a cocky there, and I married her and gave her seven children.

This remarkable story is about love, the love between husband and wife, the love between parents and children. It is immensely moving but sharp and clear like a ghost gum.

What I’m telling you might sound soft coming from a man, coming from me, but what I’m telling you is what I feel in here. It’s what I feel. I don’t tell it to anyone, not even here.

That simple, direct tone slices away sentiment and, in the manner of yarns, draws you in as stranger-confidant, the privileged one.

Yet another story commences as follows:

A man called Fingal lived with his family in a house in the shade of a great tree. The tree and Fingal were enemies.

I remember the beginning of the Laxdale Saga – ‘Ketill Flatnose was the name of a man’ – and realise that the great epics which plunge you in medias res have that magic power of yarns. You are shoved, willy nilly, into their world curious and excited like a child, wanting to know what’s going to happen and why, and what you would do if you were those characters.

Before you roar with laughter or go off thinking I’ve gone dotty, let me make one more unashamed remark. One of the joys of reading, perhaps the fundamental pleasure, lies in the magic of story, and no amount of modem scepticism ought be allowed to infringe on that joy.

Comments powered by CComment