- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A mixture of courage and an innocent hopefulness seem to be the necessary ingredients for finding rewards and compensations during the painful searching after self-knowledge. Lark Watter, the student daughter of Henry and Mrs Watter, embarks, as so many do, on the voyage of self-discovery.

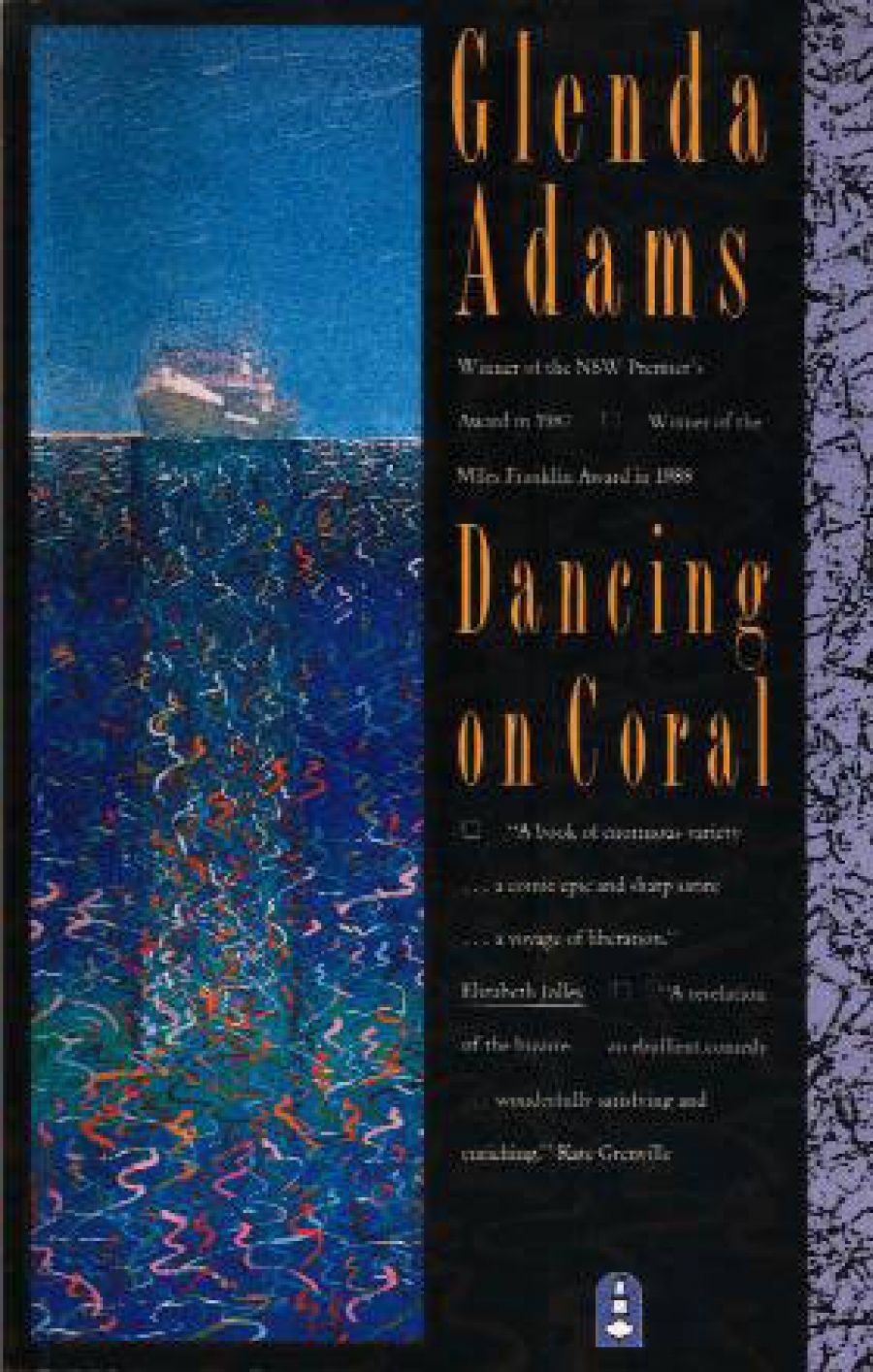

- Book 1 Title: Dancing on Coral

- Book 1 Biblio: Angus and Robertson, 291 pp, $19.95 hb 0 207 15522 4

Some readers will discover that the town is Sydney. For others the setting will be vague. A writer is under no obligation to provide a precise location for a novel but the light-hearted way in which the characters float in undefined space shows the determination of the author not to be restricted by unnecessary realism. But the book has realism enough when it is needed. The fierce and pointless argument between Lark and her mother on the topic of scrimping is a very realistic picture of family life. The larger social setting can be conveyed in a few words. Mrs Watter surveys her bag of rolled nylon stockings: ‘But these are just right for tying up the tomatoes and the vines. It would be silly to have thrown them out. After you’ve lived through a depression you can’t throw anything away.’

Mrs Watter, like Ibsen’s Gina, is a dust pan and brush character, a wife and mother, finding and accepting her place in society, making her own ‘alternative life-style’, holding her household together, at least for the time being. To Lark she remarks: ‘ “You’re home then,” said Mrs Watter. She was in the kitchen in her hat and peeling potatoes. “I never know these days …”’

She represents commonsense values in a world of inflated talk. Her husband is making a large crate and refuses to discuss its purpose. She worries that he is building his own coffin but, reflecting on the little he has said, concludes: ‘that would certainly cut costs when he goes’.

The voyage of liberation is one of the two main themes of the book. It is a voyage which is seen from many view-points. The book is set in the years after the world had largely recovered from the Second World War. It had become fashionable for the young Australian to take a trip to Europe or the United States. The Watter family is not unaffected by this fashion. Mr Watter has had his case packed for many years. Lark, a little precocious, has had hers packed since she was four. Mrs Watter has not adopted the fashion. The Watters do not appear very often in the development of the narrative, but when they do they provide a new viewpoint. In the end, Mr Watter has the last word on voyages of liberation. In a passage which is half farce and half restrained irony, he indicates the end to which all such voyages lead. Mrs Watter, finding her own liberation, places few restrictions on her daughter. Irregular appearances at meal times are met with remarkably flexible menus. The formula is:

‘Luckily it’s stew, rabbit. So there’s enough.’

The older Watters are essential to the development of the novel but the main characters are Lark, Tom, and Donna Bird. Lark makes the physical journey from Sydney to New York and to Paris. She also makes the mental and emotional journey from native simplicity of mind and heart to sophistication and a rather bitter toughness. It is a long journey and Lark often feels she has reached her goal only to find herself mistaken.

‘Lark remained awake as the train sped down the east bank…and [into] the tunnel that brought the train to Grand Central. Lark was aware that this was the most significant day of her life, that she was about to ascend to the surface of Manhattan and begin a new life, although Manhattan was not exactly the island she had had in mind when she packed her bag and planned her escape as a child…’

There is a culture to be conquered as well but Lark finds this not as difficult as she had feared. Her doubts are quickly put away. ‘ “Don’t kid yourself,” said Elizabeth, “I’ll tell you something. Just subscribe to The New Republic, The New York Review of Books and read I.F. Stone’s Weekly. That’s all it takes.”’ Lark is eager to learn and easily impressed. ‘Lark knew that she was very lucky to be sitting in this restaurant with uninhibited politically aware students. Seminal she guessed they were.’

Through Lark’s innocent vision the author is able to make sharp comment. The skilful portrait of Tom is unforgettable. He is the opposite of Lark. An intellectual Don Juan dispensing knowledge and a comforting hug to any female in distress. Often the two at once. He knows the real truth about everything and is not deceived by accepted wisdom. He is a very good specimen of a widely distributed type. Perhaps there is something of Tom in most men and many women.

Donna Bird is a modem example of what a seventeenth century writer would have presented as a ‘character’. Her rivalry with Lark for Tom provides a framework for the story. She is the one who always comes out on top. ‘But she is charming, charming.’ To which Lark painfully reflects: ‘How did Donna Bird do it? People were drawn in without fail, happily allowing her, a scavenger, to pick at them.’

The two women are the only passengers on a freighter on which they are crossing the Pacific. It is from the freighter that they make their walk ever a submerged coral reef. For Lark, at least, it is a painful and alarming walk in no way suggesting a dance. The book comes to an end with Lark making fundamental changes to her own life (it would be wrong to disclose them here). It is enough to say that she makes up her mind to get rid of the representatives of hypocrisy and selfishness ‘in the space of a baby’s afternoon nap’.

The last word is left with Lark’s parents. In a remarkable letter to her daughter, Mrs Watter reveals that she knows what has happened to her husband and that she expects Lark to know. It is a letter full of natural kindliness and common sense rounded off with a fanciful hope; ‘There’s no news at this end. Perhaps he escaped and is wandering on some island and is happy.’ Mrs Walter’s letter includes the last reported words of her husband; ‘He said to tell you – you have made your own way in this tricky world. You have done it all yourself.’

It is not necessary to accept or reject these words as an accurate summary of the book. Dancing on Coral a brilliant exposition of intellectual humbug and personal hypocrisy. It does not aim to supply wider judgements. For many it will provide illumination and reinforcement.

Comments powered by CComment