- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: War

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In a response to Peter Weir’s film Gallipoli published in Quadrant in 1982, Gerard Henderson observed that ‘recounting the story of the Anzacs has become something of a growth industry’. Five years on, the Gallipoli industry shows no sign of a downturn. The salvaging and publication of war diaries, letters and manuscripts that had long mouldered in museums, libraries and attics, the spate of ‘epic’ teledramas and ersatz war fiction (like Jack Bennett’s spin-off from the aforesaid movie), new historical studies and the resurrection of old ones such as C. E. W. Bean’s Official History and, at the other end of the scale, John Laffin’s Digger: The story of the Australian soldier (its subtitle magically changed to ‘The legend of the Australian soldier’), all attest to the enduring appeal of Australia’s military exploits to writers and filmmakers and to the subject’s ability to tap a popular audience.

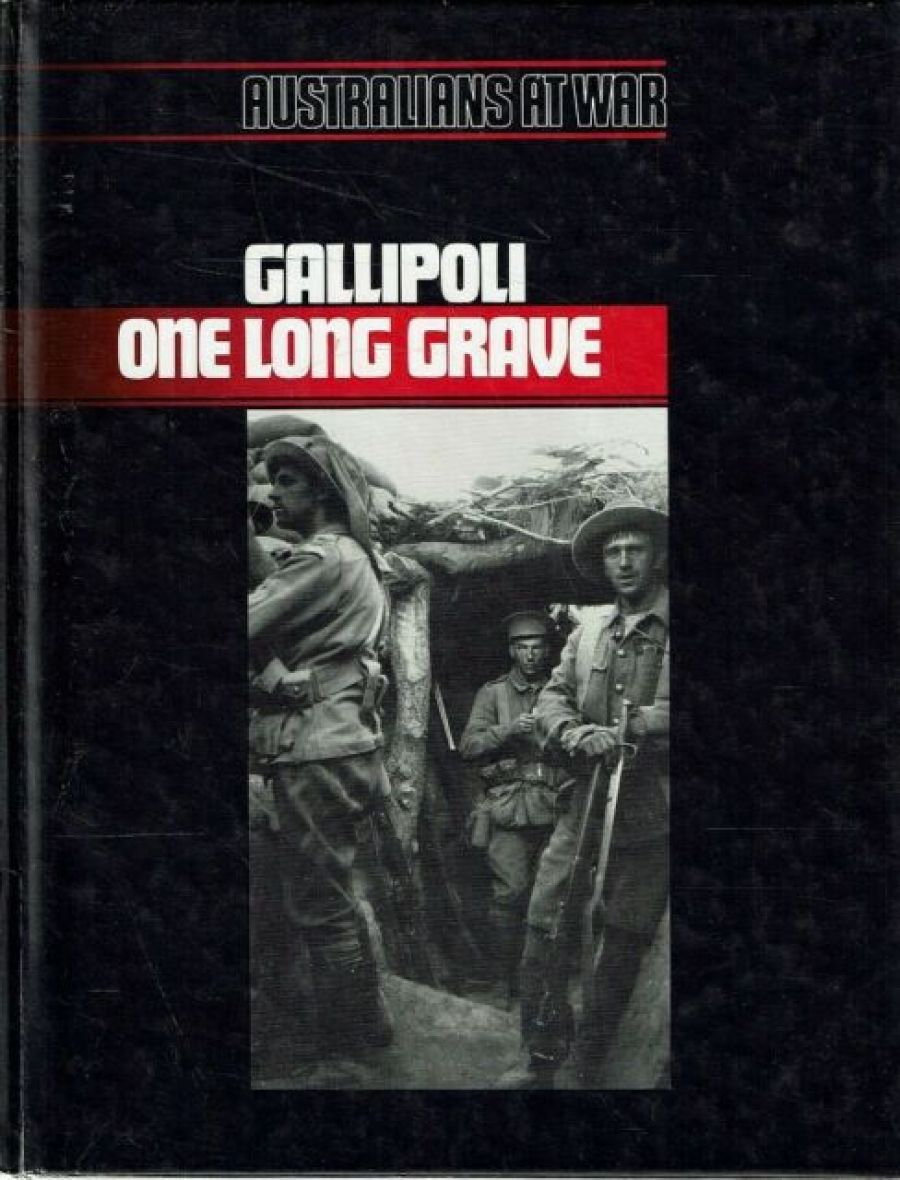

- Book 1 Title: Gallipoli

- Book 1 Subtitle: One Long Grave

- Book 1 Biblio: Time-Life Books Australia, 168 pp, $23.95 hb

And now – predictably, perhaps – ‘Australians at War’, a fifteen-volume attack on the Australian market by Time-Life Books in conjunction with the Sydney publisher John Ferguson. Apparently we should all feel grateful to Time-Life for its vision and enterprise. The series, intended as ‘a tribute to our nation as a whole’ (did Bob Hawke write the blurb?), is the first produced by the American firm for what its public relations people call an ‘indigenous’ market, and will embrace several aspects of the Australian participation in the two world wars, plus Korea and Vietnam. Time-Life has kindly paid us the compliment of allowing Australians to tell their own war story – according to Bonita Boezeman, the American managing director of the company’s South Pacific division, exhaustive research had uncovered the startling fact that ‘no one was writing war books from an Australian point of view’. (She was interviewed for the Australian.) TimeLife should sack its researchers: parochialism, often of the most unpleasantly blinkered kind, is one of the more obvious traits of what has always been a robust local war literature.

Never mind, no Australian publisher has packaged war more stylishly than in this first volume of the series, Kit Denton’s Gallipoli – One Long Grave. Gallipoli – in the dreaded phrase dutifully trotted out by Denton, Australia’s ‘baptism of fire’. It just had to open the collection. The curious thing about our continuing fascination with the ‘Anzac legend’ is the largely uncritical treatment it continues to receive. If Vietnam is a sort of military pariah, Gallipoli remains sacrosanct. Think of Weir’s romantic, eulogistic film and its screenplay (written by David Williamson), which pays such loving deference to the heroic mythology that it is difficult to believe that it came from the pen of the same playwright who is so mordant and cynical in his dramatisations of contemporary Australian society. Why do basically sceptical modern writers go weak at the knees when they tackle Gallipoli? Perhaps it is a measure of cultural pressure and the hegemony of sexual stereotyping – as Samuel Johnson said, ‘Every man thinks meanly of himself for not having been a soldier’. Or maybe it stems from a nostalgia for a distant, simpler age when it was still possible for patriotism to propel people into an enterprise ‘larger than oneself’. Such sentimentalism even manages to find its way into the complex texture of the novel 1915, Roger McDonald’s otherwise iconoclastic excursion into the psychological dimensions of the Anzac story.

Gallipoli – One Long Grave is historiographically superior to most popular war histories published in the last few years – books like Laffin’s horribly boastful Digger and Alec Hepburn’s True Australian War Tales (a work which promises to make ‘every Australian throw out his chest and hold his head a little higher’ – my emphasis). It will not, however, create any waves among the horde of Australian military enthusiasts. It says most of the right things. Denton’s account of the 25 April landings offers one example of the rhetoric that seems obligatory in books of this kind. He writes that the Anzacs

... began to forge a steel-hard legend of something like invincibility as they fought their way off a narrow and bloodstained beach and moved in and up through a killing sweep of fire.

Thankfully such passages – which seem better placed in the yellowing leaves of a wartime Age or Argus than in such a glossy, self-consciously sophisticated 1980s production – are kept to a minimum. For the most part, Denton’s narrative is restrained and balanced, and offers a detailed account of the military and political aspects of the Dardanelles campaign, together with a coverage of the Home Front reaction. Especially praiseworthy is his acknowledgement of the high percentage of emigrant Britons in the ‘quintessentially Australian’ AIF, something about which C.E.W. Bean was rather churlish. English-born himself, Denton is possibly personally sensitive on this point, although as the author of the novel The Breaker (1973) he has been a major propagator of the Boer War ‘Breaker Morant’ legend, the anti-English slant of which turned a boorish rogue into the innocent victim of vindictive British ‘justice’. (In Denton’s defence, it should be stated that he later debunked the legend he helped create: see his 1983 work Closed File.) In any case, the textual component of Gallipoli – One Long Grave is not great, and not even all that important. Essentially it is a picture book, and a classy one at that. Denton’s words form an accompaniment to a collection of war photographs (many of them unfamiliar: a minor triumph), paintings, cartoons, maps and diagrams which is splendidly produced and presented.

A new work in the ‘Australians at War’ series will appear every two months up to and running through 1988 to coincide with the Bicentennial celebrations. Some spoil-sports have already dismissed the Bicentennial as a feast of self-congratulatory chauvinism, and I suspect that those hardy souls who intend labouring through this fifteencourse literary meal will have had their fill of the Australian war experience before they finish. That may well be a healthy thing. Nevertheless, Gallipoli – One Long Grave is a reasonably appetising starter.

Comments powered by CComment