- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Ida Mann’s autobiography reminded me a little of the kind of speech that well-known elderly women tend to give to girls’ speech nights – full of zest, homely admonition, and assurances to the rows of upturned young faces that they’ll get out of life what they put in.

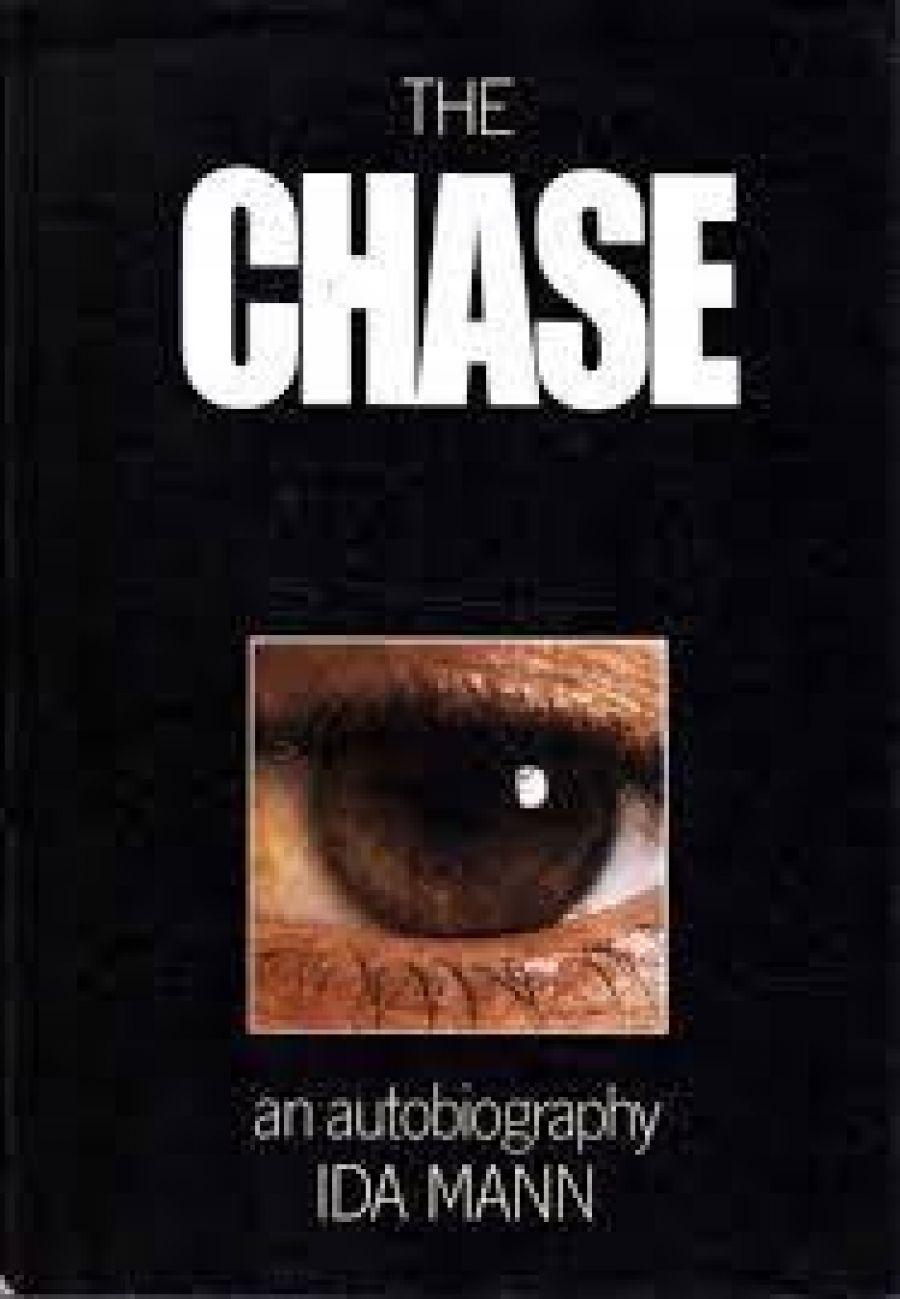

- Book 1 Title: The Chase

- Book 1 Biblio: Fremantle Arts Centre Press, 224 pp, $14.95 pb

Like so many autobiographies, The Chase has a curiously undigested quality about it. Only if you stand well back and listen carefully is it possible to pick up the moments when self-awareness breaks through the public presentation – when the voice changes for a moment or two before briskly carrying on with the account of people and places and professional milestones.

But none of this matters at all. Written, it seems, when Ida Mann was nearly eighty years old and at the suggestion of her friend Mary Durack, the book has quite rightly been reviewed as a life rather than as a piece of writing; and what a dazzling life it was. Mann was an ophthalmologist with an international reputation, the first woman professor at Oxford, beloved all over the world for her work with trachoma and other communicable diseases of the human eye.

She makes much of her rugged beginnings. ‘I started off in an unhappy uterus in a debilitated, resentful, forty-year old mother. No wonder I popped out as soon as I successfully could.’

Her first six weeks of life should have left her with a damaged sense of herself. She was born prematurely ‘on a crimson flood. I had no toenails, looked like a boiled shrimp and was bundled up and left on the floor ... Dr Howell arrived, dealt effectively with my mother and, as an afterthought, looked at me. “Goodness, it’s alive,” said he. “Don’t wash it, you might kill it.”’ She was put in care of a hired nurse, fed cow’s milk and lime juice and thrived, ‘secure but separate’, until given eventually to her mother who would thereafter treat her with guilty over-solicitude.

Ida Mann belongs to that generation of women (she was born in 1893) which broke much new ground for others, yet she would have been compelled to dismiss the idea: ‘It was simply that I had the best qualifications for the job.’

She set about obtaining those qualifications with great zeal. She left school at sixteen wishing she was a boy and could study medicine. Her ‘yearning for life as a medical student becomes almost a physical pain’ and she is eventually accepted into St Mary’s Medical School in London when the numbers of young men seeking admission fall during the First World War.

After sitting her first examinations she was ‘surprised and slightly horrified’ to find that she had scored nineties in every paper. ‘The thought came: So I am clever. This meant that I must now work very hard and try to be, and to do, something worthwhile … not merely observe.’

This sense of calling, of life being a gift, is what sets Ida Mann apart. She describes herself disarmingly as fiendishly ambitious, as ‘wanting to be one of the famous people’, as competing determinedly with her male colleagues. She was often the only women in lecture halls.

‘Ophthalmology seems a very suitable line for a girl,’ remarked her supervisor in 1920 soon after she’d taken her final exams. In a flash she made the decision to specialise and only much later realised that she’d hit upon a discipline that combined all her major interests, and was to keep her engrossed for the next sixty years.

She describes how her work fed her libido. It was her passion, her excitement in life. But her idealised and adored older brother Arthur was always at hand to take her out to dinner where they sometimes held hands and gazed into each other’s eyes feeling no guilt, which is refreshing. ‘What a pity we were not of Egyptian royal blood.’

‘Research for me … was a religion and a game, the greatest reward in life, and so satisfactory a substitute for love that I never knew for what it was a surrogate. Just the thrill of knowing I had seen something that no-one else had seen, like my aphakic embryo, kept me happy for days.’

Gradually, of course, other rewards followed. These were the ‘fat years’ with plenty of money, two houses, admirers, dinner parties and motor cars. There was lots of sturdy travel – backpacks and big boots – with women friends through the Pyrenees, India and Finland; sometimes they found themselves to be ‘so happy, they could hardly speak’.

Her brother dies and she is bereft and it is not until she is in her late forties, during the war years, that she falls in love with Professor William Gye, and they come together after the death of his wife. Her capacity for joy is enviable – his too. A touching photograph shows the two of them on their arrival in Australia, radiating pleasure in each other.

Ida Mann and William Gye lived in Perth for the few years that they had together before his death which ‘nearly unhinged her’. ‘I felt as emotionless as a centurion. Isolation was complete. Freedom was utter.’

She includes in the book a poem called ‘Love and Loss’ written some years later.

My love, I love you with an all-consuming passion

Till all earth’s beauty is a garland for

your neck,

Till the great old trees of autumn are a

background for your manhood

And your burning dark eyes come

between me and the stars.

Then the Flying Doctor Service wanted an ophthalmic surgeon to make a short trip to the Kimberleys and report on eye diseases there. Ida Mann discovered trachoma among the Aboriginal children in numbers she had never before encountered. She became engrossed with the outback and her research again. ‘Here was something completely new, luring me away from the easeful sunshine of professional success and its comfortable rewards.’

For the next four years she carried out a major identification project, finding over ten thousand Aboriginal people infected with trachoma, and 144 already blind. Her reputation in the field took her all over the world. She published in her lifetime over 150 scientific papers as well as books on her travels.

But it was her energy and resilience, her ability to respond to people with sensitivity and excitement, that friends remarked on most, and that she reveals in the course of her account. Somehow that little baby – the only baby in the book, as it happens – grew up able to empathise with others, reaching out to them constantly from the reserves she found inside herself.

Comments powered by CComment