- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

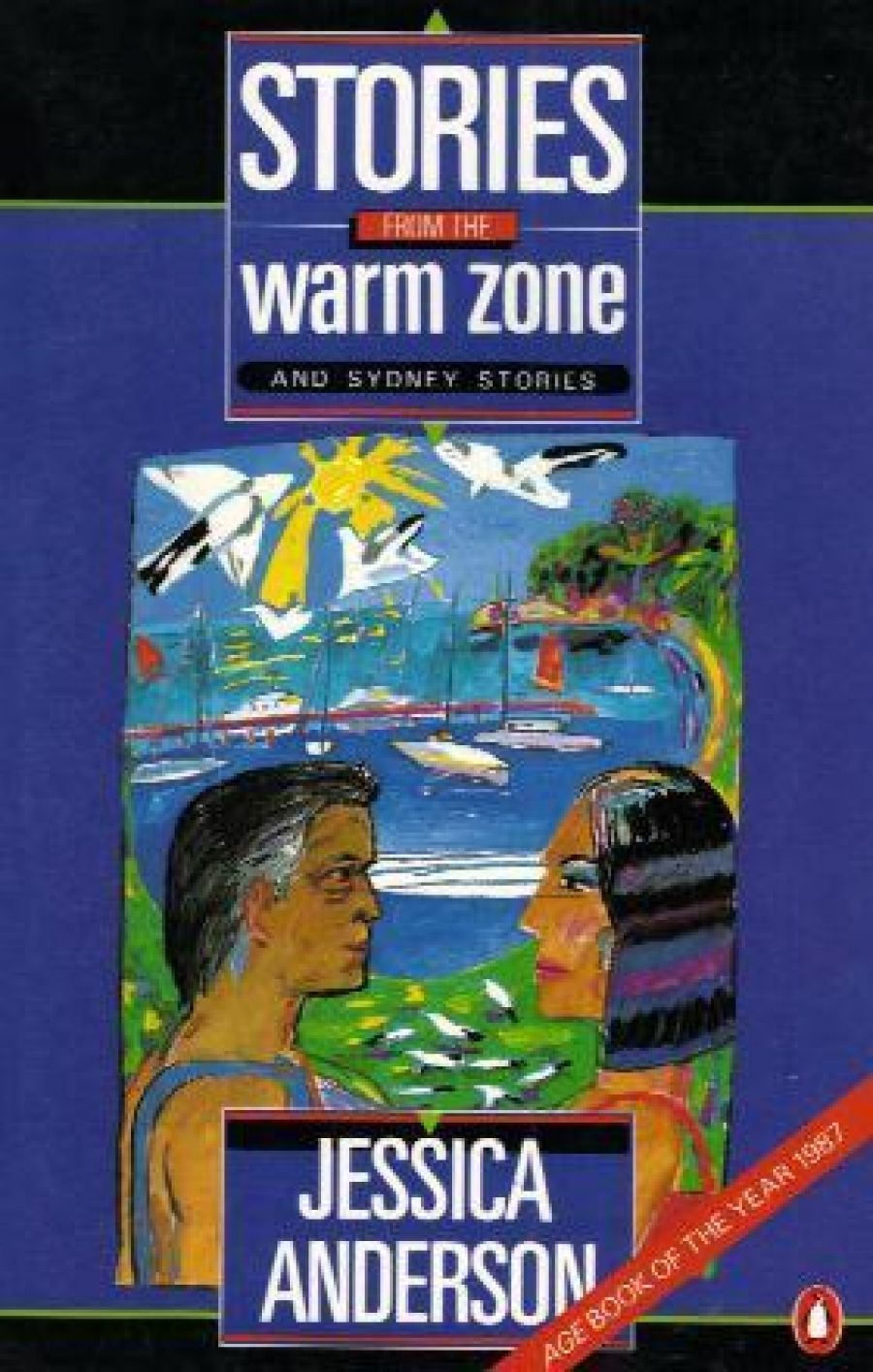

In her interview with Candida Baker for Yacker 2, Jessica Anderson expresses her dissatisfaction with the covers of a number of her books, citing in particular the glum face on the paperback of The Impersonators and the representation of The Commandant as, in Baker’s words, ‘a Regency romance’. Anderson, who began as a commercial artist, stresses that ‘Design and presentation ... really matter. They’re the introduction to a book.’ It seems to me to be particularly unfortunate (although she may well have given it her blessing) that her new book sports a clichéd Ken Done cover. Perhaps Done’s bright colours might evoke the ‘warm zone’ of the title, although Anderson is referring to Brisbane, not Done’s mock-naïve view of Sydney. Unfortunately, the cover subliminally suggests that Anderson’s writing is sunnily comforting, easily assimilated.

- Book 1 Title: Stories from the Warm Zone

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, $9.95, 245 pp

That is, perhaps, an easy mistake to make. Anderson’s stories are certainly easy to read. As she pointed out in her interview for Jennifer Ellison’s Rooms of Their Own, Anderson is, in her writing, ‘interested in families’; and that is, surely, a novelistic cliché. But the families have always been viewed from their borders by an involved but still distanced character: Frances in The Commandant, Nora in Tirra Lirra by the River, Sylvia in The Impersonators. In this new book, her first collection of short stories, Anderson continues to explore this oblique and often ambivalent view of family life.

This volume contains five ‘Stories from the Warm Zone’ and three ‘Sydney Stories’. (I must say that for a Melbourne reviewer writing during an exceptionally wintry few days, Sydney counts as a warm zone too!) In keeping with Anderson’s complex view of families, no easy division between the childhood ‘warm zone’ stories and the fracturing marriages of the Sydney stories should be made, despite the suggestion of the jacket blurb. The author explains that the sequence of stories set in Queensland, and seen through the eyes of a child, Bea, are what she calls ‘autobiographical fiction’. Anderson suggests that the technique she has used is primarily designed to enhance what I have been calling the view from the borders of the family:

Though I have been true to the characters of my immediate family, and to our circumstances and surroundings, few of the events described occurred as written, but are memories fed by imagination and shaped by the demands of the narrative form. As a reflection of this fictional content, and to put myself at a necessary distance while writing, I changed the names of the characters and of various streets and places.

In the sequence of stories, Bea, the youngest of three sisters, is first spotted in that ambiguous Queensland realm of shape-shifting, ‘under the house’, described so eloquently by David Malouf in 12 Edmondstone Street as ‘the underdark’. Bea’s perspective is thus oblique initially, and as the stories proceed, her stammer (one sign that she represents, in a fictional form, the author herself) leads to her removal from school for a year. Her experience of this is related in a key story, the superbly crafted ‘The Way to Budjerra Heights’. At this stage of the sequence, we realise how easily ‘warm zone’ mutates linguistically (through a stutter, perhaps) into ‘war zone’, that these stories are not simply celebrations of a childhood idyll in familial security – though such elements are present. ‘The Way to Budjerra Heights’ makes subtle and telling use of a double time scheme; the immense tact and skill in this comes as no surprise from the author of Tirra Lirra by the River. Bea’s time alone in the house with her mother as a child is merged with a much later time:

But when I hear her whispering alone in her bed at night, I know that the woman in her eighties, walking about the house and garden, threatens to absorb the rigorous middle-aged woman who supervised my lessons that year, and whose sick husband still lay beside her at night. In our lives, there were two spans of time when she and I were alone in the house together every weekday, the first lasting for a school year, the second for only a month. They have become ravelled together, and deliberation is needed to untangle them.

The childhood and adult knowledges merge to question this warm family, as Bea’s aged mother lashes out at her long-dead husband’s ‘weakness’ (‘Your father gave in’), and a peculiar complicity is established on Bea’s part, a complicity that involves a questioning of what it is that breaks through (or fails to) the patterns of expectations that clog all social interaction, families included: ‘Though my father had become one of those to whom I could not speak without stammering, he remained, if less beloved as a man, a beloved and remote figure …’

It would be wrong to leave the impression that this story sequence is as unrelentingly sombre as these quotations may imply. Anderson’s characteristic dry humour is present everywhere, but it also characteristically resists any easy transformation into the genre of ‘amusing childhood reminiscence’, just as Anderson’s other books break open generic demarcations: The Impersonators works on the family saga, The Commandant on the historical novel, Tirra Lirra by the River on the ‘woman’s novel’, and even The Last Man’s Head on the detective novel/thriller.

Another superb story in the sequence is ‘The Appearance of Things’. This begins with an example of Anderson’s brilliant use of dialogue (she has attributed her affection for and skill with dialogue to her radio writing):

‘Rhoda wants to go to church,’ said my mother.

‘Now why?’ said my father. ‘Why should Rhoda want to do that?’

‘She has become friendly with Helen Scott.’

The amusing tale of Bea’s two sisters taking up religion is also an exploration of the title’s implications, from Bea’s fascination with the new name that baptism will allow her to assume, through to the disturbing conclusion, which once again involves a dramatic and effective time shift: ‘I wept long and hard when Rhoda died. I was in my thirties, she in her early forties.’

The place where form or self-presentation meets and is undermined by passion, in many ways the principal theme of The Impersonators, is examined retrospectively by Bea:

‘What was he like? Do you remember?’

‘Oh yes,’ I said. And I went on to describe him – his manner of bending, his fine light bones, his narrow head, his unused hands, his silver hair, never once pausing to reflect that that was not what Rhonda’s widower had asked me. He had not asked me what Mr Gilliard looked like.

The three Sydney stories which follow the sequence of ‘warm zone’ stories are also concerned with the problems of what Bea calls ‘‘reading’ people’, and with the precarious relationships that make (and unmake) families. As it is in The Impersonators, Sydney itself is an important character in these stories. ‘The Milk’ centres on Marjorie’s divorce, a 1976 divorce:

The divorce laws had been reformed the year before, sweeping away grounds such as adultery, cruelty, and desertion, and putting in their place only breakdown of marriage. Carla said, ‘He can’t believe you can leave him, and not be legally punished.’

Marriages in the Sydney stories don’t spectacularly break up, they break down. What might have been an easy story about Marjorie finding her independence as she takes up a full-time career as an illustrator is again characteristically complicated by her tussle with a milkman, who is reluctant to provide her with the simple milk delivery that seems to symbolise a false ease with her new life. This is a story of small victories.

On the surface, the next story, ‘The Late Sunlight’, might seem to be the exception to the theme, as Gordon, a historian undertaking research in Sydney, has a happy marriage, and the story focuses on a few encounters he has with a dying Hungarian countess (a character only Anderson could see without producing a parody). But Gordon reveals that the theme does persist:

He sometimes felt more genuinely a part of his family when away from them than when at home. There, he occasionally had the curious feeling that he had had no part in their making, but that he had come gambolling to their door one day, and they, calmly, smilingly, kindly, had taken him in and given him a good home.

The final story, ‘Outdoor Friends’, is almost a novella in length. In another echo of The Impersonators, ‘Outdoor Friends’ sets up a situation that could be called near-incest. Owen Thorbury, after he leaves his wife, has an affair with Freda Thewen, the mother of the man his daughter has recently married. This flirtation with a situation that isn’t really incest at all, but is still touched by the taboos associated with it, adds to Anderson’s wry view of passion, individual development, and families. ‘Outdoor Friends’ is full of marvellous observations of the bond between Owen and his three very different children. His affair with Freda engages him in a process of unknowing; whenever he feels he has pinned down the emotional overtones, he is disappointed. Anderson constantly depicts the sudden shifts of awareness that the affair provokes, and writes with a wonderful economy and depth of feeling:

When he rose and they stood face to face he was startled by the lines across her forehead and round her mouth. As he had sat with his cheek embedded in the flesh of her belly he had had the illusion that they were both young. And he saw by her eyes, fixed for a moment on his face, and so tense and inquisitive, that she had shared the illusion. They both laughed, but Owen thought it was sorrow they mocked, and to console or assure her he would have embraced her again, but she turned out of his arms, shaking her head, and wrapped the towel under her armpits.

By the end of the story, Owen remains puzzled at the marriage which Freda protects at such apparent cost. His thoughts of the future christening of their mutual grandchild lead to his final reflections on a situation that even his empathy cannot comprehend:

And there they would be: the Thewens. By that time he would have learned more about her, and more about him, and about the conjunction would know less than before. He would never know what the Thewens were really like.

This rewarding collection of stories will not disappoint readers who have come to expect the highest literary achievement from Jessica Anderson.

Comments powered by CComment