- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

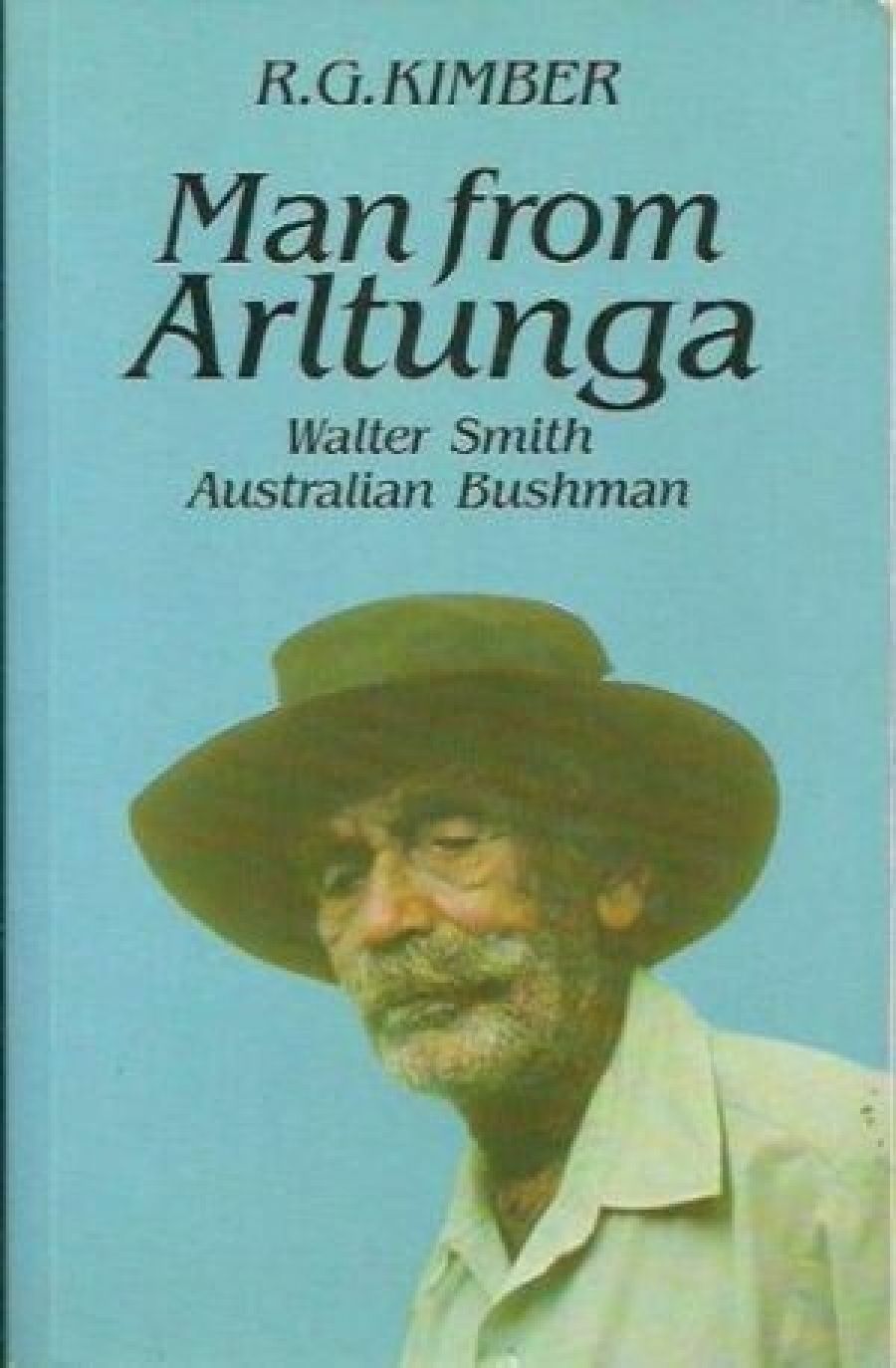

- Article Title: The Last of the Camel Men

- Article Subtitle: A bushman's tale, romantically hued

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Much that is published on the Centre is from the perspective of the jet-and-chopper journalist, so it is with sheer delight that one greets Man from Arltunga, written from the perspective of a local and a bushman. The author’s knowledge of this country is of a rare quality. Not only is he interested in the White settlement of the area but he also has a broader appreciation for the prehistory and for the Black version of their history. In the thirteen years that Dick Kimber has lived in the Centre he has travelled extensively with Aboriginal people through their ancestral country. He has travelled the Aboriginal way, with Aboriginal navigators, journeying slowly, digressing for relatives, or for bush tucker, or for ceremonial business. His first-hand knowledge together with his affinity for the country made him an ideal companion for Walter Smith on their journey to record Walter’s story.

- Book 1 Title: Man from Arltunga

- Book 1 Biblio: Hesperian Press, 193 pp., $22.05

Walter Smith is the last of the camel men to relinquish his team and one of the last of the true bushmen of Australia. He is also the last man to be put through all degrees of Eastern Aranda men’s law. Born in 1893, Walter has lived in the Territory when much of it was still being ‘discovered’. His career as a bushman began like that of many a boy of his times – as a horsetailer. Unlike many, Walter seemed to thrive on new experiences. He worked at mining and prospecting and became an accomplished cameleer whilst working for Sadadeen, an Afghan.

Walter had his first real job at the age of twelve, working for Billy Coulthard a job involving 4000 kilometres of riding. For many years he worked at cattle and horse droving, often in enterprises which involved borrowing and selling to the same owner. He tells the tale of mustering cattle that were lifted from Kidman’s New Crown Station whilst riding a horse stolen from Bloods Creek.

Droving cattle and horses meant traversing some of the most desolate country, from Urandangi and Camel’s Soak (Mt Isa) to Newcastle Waters, or from the MacDonnell Ranges through the Simpson Desert to markets at Adelaide. Walter has this to say of one of these trips:

Before you get to the Birdsville country there might be a sandhill, might be ten feet high. In the morning when you get up, it’s not there! And you’ve got a job to get out of bed too, because you’re buried up in that sand, shifting sand, white sand. We reckon that was great. No policeman will follow us.

As a cameleer Walter’s contribution to the country was in carrying all manner of goods – minerals, salt, cement (which he reckoned was the worst when the sky clouded up). Working out of Oodnadatta the camel trips took him across the Musgraves to Kalgoorlie, to Marble Bar and back, an epic feat even with today’s transport.

Walter’s fluency in Aranda and other Aboriginal languages made him at ease with Aboriginal etiquette. In times when Aborigines and Afghans were shot for ‘being cheeky’, this skill was invaluable in ensuring smooth travel. Between 1924 and 1929 he participated and was initiated into the Rain and Red Ochre ceremonies of the Pitjantjatjarra and Eastern Aranda. He accepted the role of law man, the training for which involved painful operations and a great deal of responsibility. It also meant travelling in tribal territory deep in the Simpson, learning the secrets of survival.

Walter Smith’s story is worth knowing and wherever possible is told in his own idiomatic style. He has a yarn for every bit of the country, stories of the pioneering men whose deeds left them indelibly etched in the collective memory as characters of the Centre. Modern Alice Springs and its environs owe much to these men and Walter Smith worked with and knew many of them. He is also familiar with the land associated with Dreamtime ancestral figures and played his part in the Lasseter Legend.

In allowing Walter to tell his story his own way Kimber has shown respect for his privacy. Kimber has used the only approach that could have worked in interviewing a bushman. Knowingly or unknowingly he has used the old Aboriginal way of not putting himself forward, in both the listening and the writing of the account. And if Walter is unassuming about his role in the history of the continent, the author’s unobtrusive yet informative narrative blends well with the tale. Perhaps this explains its romantic hue and the meandering chronology in the latter part of the book. The inclusion of a chronological chart would have strengthened the structure, especially as Kimber has thoroughly researched the primary sources and yarned with old-timers in order to corroborate the authenticity of this oral history.

Man from Arltunga is mandatory reading for all those who wish to share the romance of the swag.

Comments powered by CComment