- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

As Meena Blesing explained in an interview on Sixty Minutes, writing an autobiographical account of her life during the Combe-Ivanov Royal Commission was something she needed to do. Writing the book allowed her to discuss the events of 1983 and their consequences in a way that gave expression to and ordered her anger. For the reader, Blesing’s very personal story provides a perspective on the Combe Affair which has not been canvassed in the other published material: media reports, the Hope Report, David Marr’s The Ivanov Trail. That the book concludes on a note of somewhat ironic hope is but one indication of the emotional complexity of the material story, she covers. For, in telling her own story, Blesing also presents us with what can be read as a rare discussion of the impact on private, family life of state actions and policies.

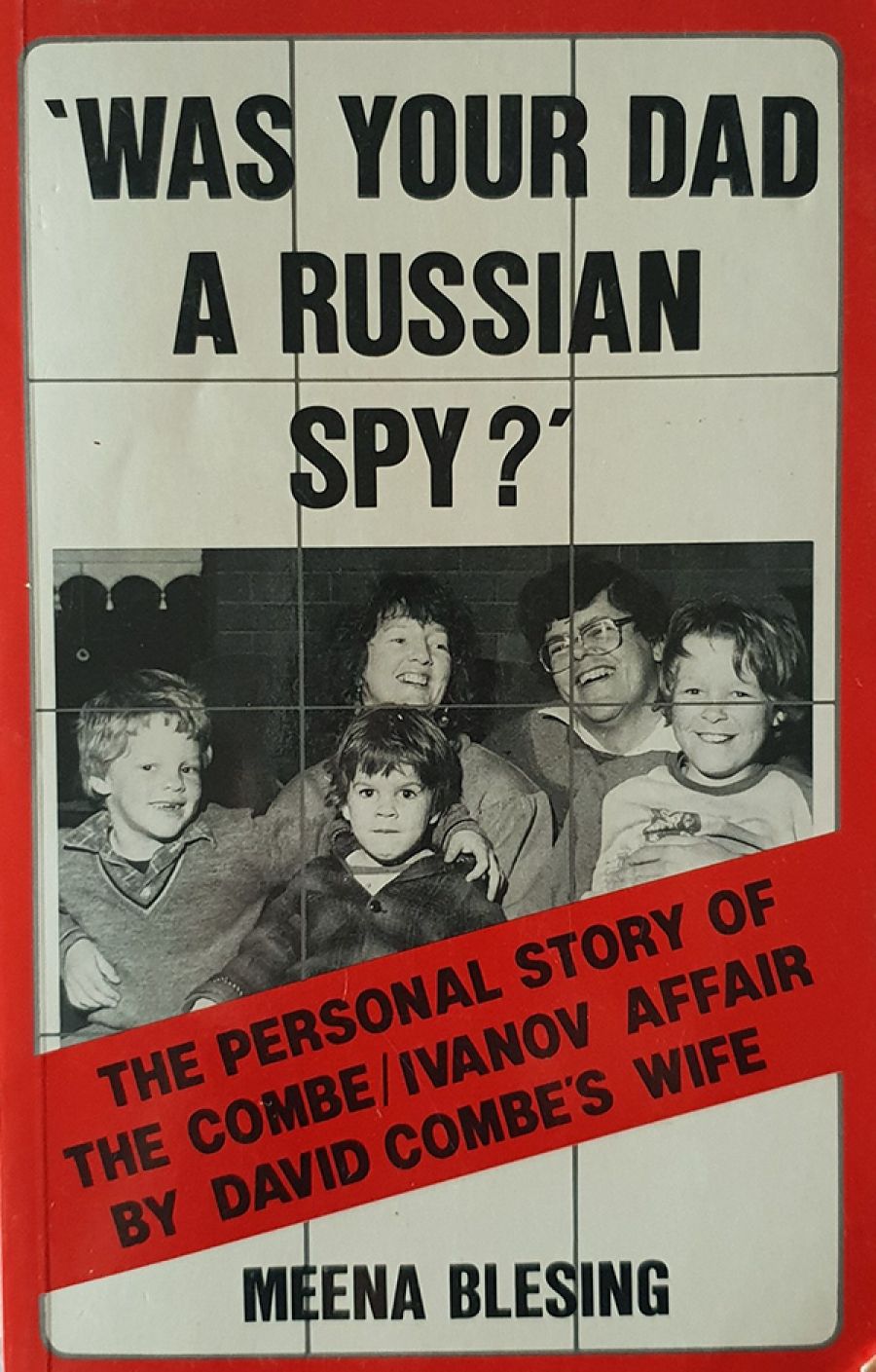

- Book 1 Title: Was Your Dad A Russian Spy?

- Book 1 Subtitle: The personal story of the Combe/Ivanov Affair by David Combe’s wife

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan, 223 pp, $9.95 pb

Having recently made the transition from being the wife of the ALP National Secretary to being the wife of a consultant and joint director of their company, Blesing was glad to leave the pressures of public life behind. Her disillusionment with ALP polities and with the personal behaviour of many in politics, often men, had also led her to look forward to getting on with her own life: art, yoga and meditation, gardening, work in the business, bringing up four children. The demands of public responsibilities and the media on politician’s families are great, particularly for wives like Blesing who also desire an unconventionally independent life.

Ironically, it was after the departure of David Combe from party officialdom that the Combe family faced their greatest public exposure. The accusations and innuendoes levelled against them seemed like madness to Blesing and Combe who for many years, in the knowledge of their innocence and their wish for a normal life, had refused in relation to their own lives to take ASIO and its more paranoid fantasies seriously.

The book functions as a defence of Combe, but that is not its central preoccupation. Combe’s innocence is instead the underlying assumption from which Blesing writes of the cost in personal terms of the Commission’s allegations. The cost included a temporary separation from her husband. For Blesing, Combe’s innocence becomes proof that the events experienced by the whole family are akin to madness. She charts her responses to the fears and paranoia that were produced in a period when her private life was restructured by the state almost to the point of the extinction of any privacy. The book draws on diaries, letters, remembered conversations and Commission material to construct a picture of a life which included the demands of children as well as those created by government, personal and political responsibilities all requiring Blesing’s careful attention.

Private life tends to get short shrift in public discourse which concerns itself with what it sees as more important things. So trivial was Blesing for the public record that ASIO in its muddled transcribings and Justice Hope for his own convenience continually got her name and contribution to the family business wrong. Interestingly, Hope also refers to Jvanov’s wife by an incorrect version of her name, again for his convenience. Minor as this may be in the overall context, these signs of her lack of individual existence in the eyes of the state added to Blesing’s feelings of helplessness and, no doubt, helped fuel her resolve to speak in this book for herself. What she does here is speak from the marginalised position of private life to argue for its importance and simultaneously refuse the role of political outcast.

The book is structured like a descent into and emergence from madness, as the family lives through the Commission. Blesing shows the impact of the relentless procession of legal and media events on their day to day lives. Here, scrubbing potatoes coexists with telephone calls from journalists and politicians, all monitored, as it turned out, by ASIO. Public events were not so much a backdrop to her daily life as intertwined with it, yet her ability to influence those events was minimal. Rather there was an attempt to negotiate events by providing support for Com be, support for the children, receiving support from friends, taking time off for herself. The pressures were enormous and the emotional needs and reserves of the members of the family not always in harmony.

Remember that at this period the media became for Blesing a report on and a barometer of her own life. Circumstances were such that sometimes she could only follow her husband’s whereabouts by watching television. Rather than a report of external events, her own fortunes were reflected back at her from the TV screen. Yet one of the strengths of the book is the way her depiction of ordinary life in extraordinary circumstances is combined with a critique of the political and judicial system. By the end of the book, Blesing identifies the Commission and the government as not only functionally unjust but structurally anti-human. She frequently mentions that Combe was not seen as a person and that she and the children appeared not to exist at all.

Like many others, Blesing is no wiser at the end of the Commission than at its beginning of the reasons for its institution. Did Matheson as an ASIO informer set the whole thing up? Were there connections with secret foreign espionage arrangements? So empty and unsatisfactory was the Commission as a way of casting light on events, its main purpose seemed the reinforcement of the status of the law and the legal profession, the perpetuation of the lie that justice is both done and seen to be done.

The still unresolved controversies of the Combe Affair will lead to different readings of Blesing’s book. Judy Fasher in an interview on ABC Radio’s ‘Tuesday Despatch’ allows for a sympathetic and serious discussion of the issues Blesing raises, but two other reviewers have been quick to use their more conservative politics as a starting point for dismissing Blesing’s interpretation, particularly in regard to the civil liberties aspects. Interestingly, both Thelma Forshaw in The Age and David Harris in The Advertiser share a distaste for Blesing’s description of the personal aspects of the injustices she faced. Forshaw, in particular, see this as ‘self-aggrandisement’, as Blesing wanting to get in on the political act. Further, both Forshaw and Harris use Blesing’s frankness about her then membership of the Rajneesh sect as an excuse for undermining her overall argument. Members of other religious groups like Seventh Day Adventists and the Ananda Marga have for not dissimilar reasons been defined in Australia recently as beyond the pale. Such churlishness about a faith which, at the least, helped Blesing through a difficult period causes this reviewer to wonder how Forshaw and Harris might have responded had Blesing been a more conventional wife practising a more acceptable religion. But perhaps we wouldn’t then have had a book like this at all.

At this point it is necessary that I make my personal sympathies with the Combe family clear, my political sympathies already being apparent. As an undergraduate student in Canberra in the mid-1970s I was for over three years the regular babysitter of the elder Combe children, an experience on which I look back with great pleasure. The children were imaginative, lively and intelligent, and I can visualise well their performing an impromptu spy show for the television cameras, as Blesing describes. But what I also gained from my babysitting was an insight into the pressures faced by politicians’ families, both under normal circumstances and during political crises, pressures that were to be exaggerated so dramatically in the course of the Commission. During the 1976 Iraqi Breakfast Affair I took Nep and Solly to parks, on walks, anything to get them and myself out of the house and away from the non-stop telephone and the journalists who came to the door even at eleven or twelve at night. So short of gossip were they that one hapless reporter hoped for a story on the babysitter!

My small experience of the kind of life Blesing describes is only one reason for my support here of the seriousness of her discussion. There are others, for the book speaks for those who don’t make decisions and asks that their lives be of public concern. In extending the material available on the Combe Affair, she contributes to its scandalous implications remaining on the agenda of Australian political and civil liberties discussion. In showing how the Combes got through their crisis she insists in the face of the Commission on always maintaining her humanity.

Comments powered by CComment