- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Living with Stress and Anxiety is the title of one of those self-help guides put out by Manchester University Press in its ‘Living With …’ series; Living with Breast Cancer and Mastectomy is another. Living with Literary Theory is not a scheduled volume, I imagine, although some people who work in the lit. crit. business seem to regard literary theory as a prime source of anxiety for which the only remedy is theorectomy. In the decade since Terence Hawkes first taught us how to live with Structuralism and Semiotics (1977), Methuen has succeeded admirably through its expository ‘New Accents’ series (edited by Hawkes) in making it easier for everybody to cope with such anxiety-provoking processes as Lacanian psychoanalysis or Derridean deconstruction; too easy, in the opinion of those who them-selves feel uneasy at the politics of marketing criticism’s nouvelle cuisine as fast-food takeaways, with Methuen playing the role of the big M.

- Book 1 Title: Criticism in Society

- Book 1 Biblio: Methuen, 244 pp, $52.95 hb

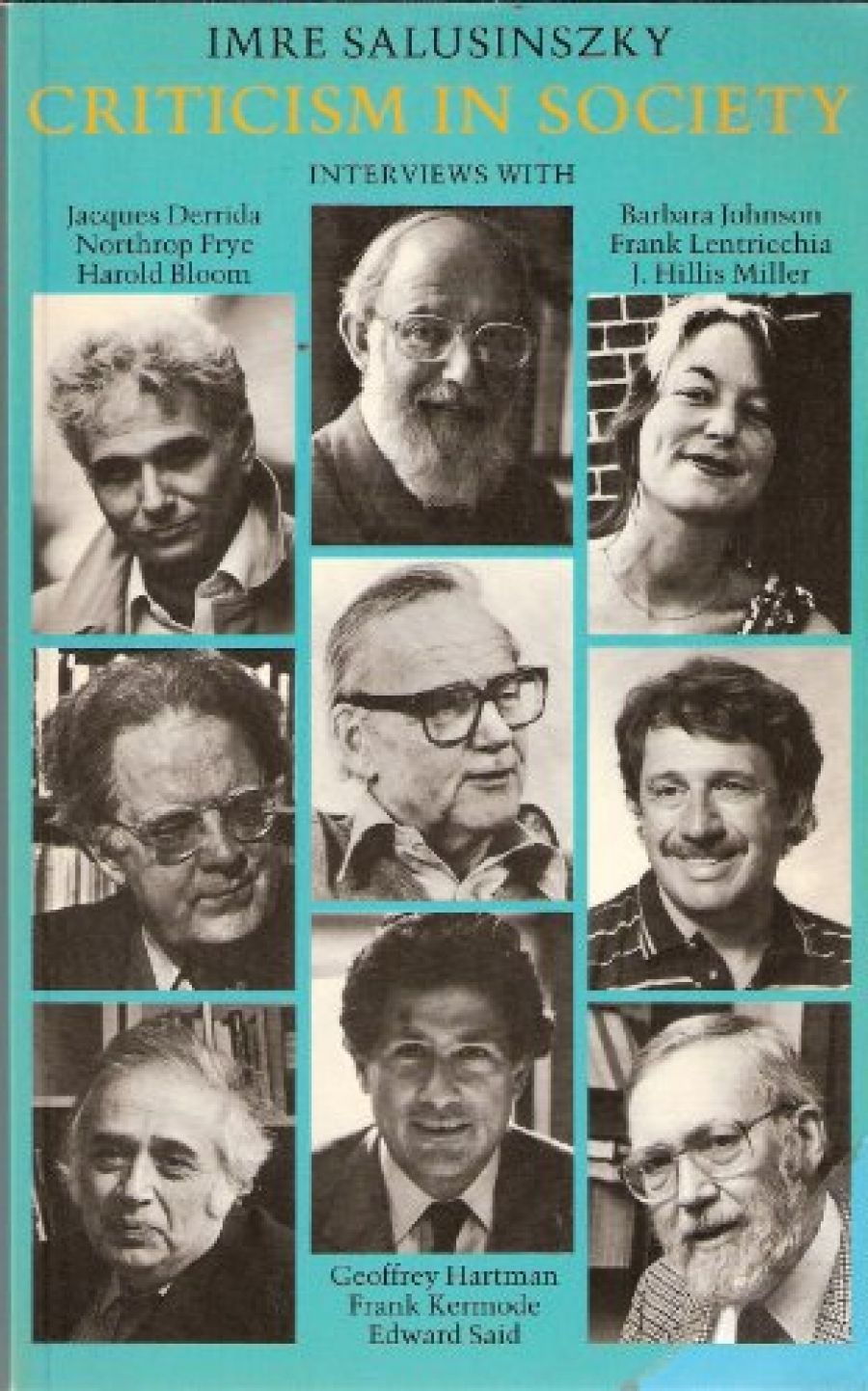

The tenth anniversary of this outstandingly successful series is celebrated unexpectedly with a book of interviews conducted by a local gourmet of critical practices, Imre Salusinszky, with some of the chefs. Two of these interviews were first published in Australia, the one with Harold Bloom in Scripsi, and the other with Jacques Derrida (the very first he has ever given in English) in Southern Review; but none of the others has appeared anywhere in print before. Interviews with writers are encountered commonly enough, and some of them are done extremely well, like the Paris Review series. But interviews with critics? The very existence of Salusinszky’s book acknowledges the new criticism’s boldest claim: in its weak form, that the critical act is just as ‘creative’ as creative writing; and in its strong form (as put by W.J.T. Mitchell at a recent Humanities Research Centre conference in Canberra on literary journals), that the avant-garde nowadays is constituted not by creative writers in the old sense but by critical theorists.

The opening interview is with that brilliant French philosopher Jacques Derrida, whose proof of the groundlessness of all claims to origin or centre or presence in discourse was to become, ironically, the grounds of Anglo-American deconstructive criticism. He is followed by Northrop Frye, the Canadian typist turned critical typologist, whose Anatomy of Criticism (1957) first opened up the possibility of a systemics of literary study.

Next come a couple of Yale celebrities: Harold Bloom, best known (although it appears to worry him) for reconceptualising in Freudian terms the idea of literary influence as an anxiety neurosis; and the colleague he calls ‘the Ayatollah Hartmeini’, Geoffrey Hartman, whose magisterial writings reveal a seemingly effortless assimilation of every significant critical development over the last three decades. The only Brit in Salusinszky’s gallery is Frank Kermode (the ‘Frankie Mode’ of a Clive James satire), whose centrality as a mediator between newer and older ways of writing about writing is represented by the positioning of his photograph on the jacket of the book and his interview inside it.

There is a potentially awkward moment when the Hungarian-born Jew from Melbourne meets the Palestinian Arab from Jerusalem, Edward Said, but it is negotiated skilfully. As a survivor of death threats and raids on his office, Said is acutely aware of the political contexts in which writing takes place, and his account of exploitative constructions of the east by Eurocentric imperialists has made his Orientalism (1978) a model for postcolonial enquiries into the cultural tyrannies of imperial ideologies.

A transition from politics to sexual politics looks possible in the pages occupied by the only female interviewee, Barbara Johnson, but nothing much comes of it. For although this former student of deconstruction’s most rigorous exponent, Paul de Man, thinks the duplicities she experienced in growing up female in a man’s world gave her an aptitude for deconstructive analysis, she doesn’t come across as being much interested (in the way that Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak is) in using deconstructive skills to firm up a sexual politics.

And so, we come to Frank Lentricchia, a working-class boy (so many of them were, it seems) who made it, wrote an influential book called After the New Criticism (1980), and has now convinced himself, as he draws his professorial salary, that ‘the only serious site of Marxist struggle in the United States is in the university’.

Salusinszky’s final encounter is with the prolific and charming apologist for deconstruction, J. Hillis Miller, who is placed in the privileged position of commenting on all the other interviews. It is a valedictory moment in several senses, for Miller was about to leave Yale for Irvine, California, taking (as it turned out) Derrida with him, and hastening the end of that deconstructionist moment symbolised by the death of Paul de Man.

Why choose to represent contemporary criticism by interviewing these people and not some of the others, like Jonathan Culler, or Stanley Fish, or Fredric Jameson? Well, Salusinszky taught at Yale for a year, and the people he interviewed were either there or within reach. Had he stayed longer; his book might have been bigger. Had he gone to Berkeley instead of Yale, he would have met Stephen Greenblatt and west-coast new historicists would have been represented in some other book as strongly as east-coast deconstructors are in this one.

Criticism in Society is attractively produced. It is prefaced by a short introduction, and at the beginning of each section is a photograph of the interviewee and an outline of the characteristics of that person’s writing. Lists of their principal publications are printed at the end of the book, where I looked in vain for an index to help me check quickly whether I’d merely imagined Bloom referring to Fish as ‘the Fishyfoo’ (I hadn’t: see page 54). Salusinszky’s text is lightly annotated, perhaps too lightly: will everybody recognise ‘Joe Frank’, and know where to find not only his three-part essay on spatial form in modern literature but also Kermode’s disagreements with Joseph Frank on this matter?

To effect a kind of unity in diversity, Salusinszky asked his interviewees to comment on a short poem by that darling poet of theoreticians, Wallace Stevens, ‘to highlight how different critics begin the process of criticism, how they begin to work with a poem, and what they look for in it’. By and large they cooperated, and revealingly, although Derrida doesn’t seem to have been asked for an opinion; and when Salusinszky went to interview Kermode at Columbia he forgot to take with him a copy of ‘Not Ideas about the Thing but the Thing Itself’. Unperturbed by this lapse, Kermode tried to say something about the poem nevertheless, and then gave Salusinszky a copy of a sonnet by John Peale Bishop which turned out on closer inspection to contain an obscenely dismissive acrostic.

Salusinszky got his Ph.D. for research on Northrop Frye, but he wears his considerable learning lightly, and his experience as a literary journalist has enabled him to produce a highly readable and entertaining as well as informative book. He did the necessary homework before every interview, identified and asked some leading questions, and had the good sense not to pursue every tendentious remark made by his celebrities, who in some cases (Bloom especially) gave away far more than the questions invited. Salusinszky’s style is rather more formal in his prefatory remarks than in the interviews themselves, when occasionally he dons the mask of ocker brashness before enquiring urbanely into matters which well-bred persons think about but would never dream of mentioning, as when he asks Hillis Miller whether his withered arm caused him to have a bookish childhood (‘It is a good thing that an Australian is doing these interviews’ he reassures Miller, ‘because it is necessary to be quite without tact, and Australians are naturally gifted in this regard’). What we now need, of course, is somebody with Salusinszky’s energy and initiative to interview these people again, this time to find out what they all thought of our Imre …

Criticism in Societv is a book which will appeal to different sorts of readers. If you know all about recent literary theory then you’ll enjoy reading what this galaxy of superprofs is coaxed into saying about it, and in some cases about one another. If you don’t, but would like to, then this is a good place to start, for it’s a more attractive because more personalised introduction to part of the subject than any of the available introductory guides, which emphasise schools and methods rather than the personalities of the people involved. It should certainly be required reading for all those intellectual derros who complain in the literary pages of our newspapers about the ‘jargon’ of contemporary criticism. Salusinszky’s book should help them overcome their fear and loathing of something they really ought to know about, if only as an antidote to the superannuated chatter they themselves serve up as literary criticism.

Comments powered by CComment