- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

David Foster is obsessed with opposites. He likes to play polarities of place and value against each other: in The Pure Land he contrasted Katoomba and Philadelphia, the sentimental and the intellectual; in Plumbum he put Canberra against Calcutta, the rational against the spiritual. At a talk in Canberra several years ago, he commented that it was the symmetry of the words Canberra and Calcutta that attracted him to the idea of the cities as polarities. Words themselves invite Foster to play games with meaning and suggestion, and he finds an endless source of absurdity in the gap between actuality and the words chosen to label it.

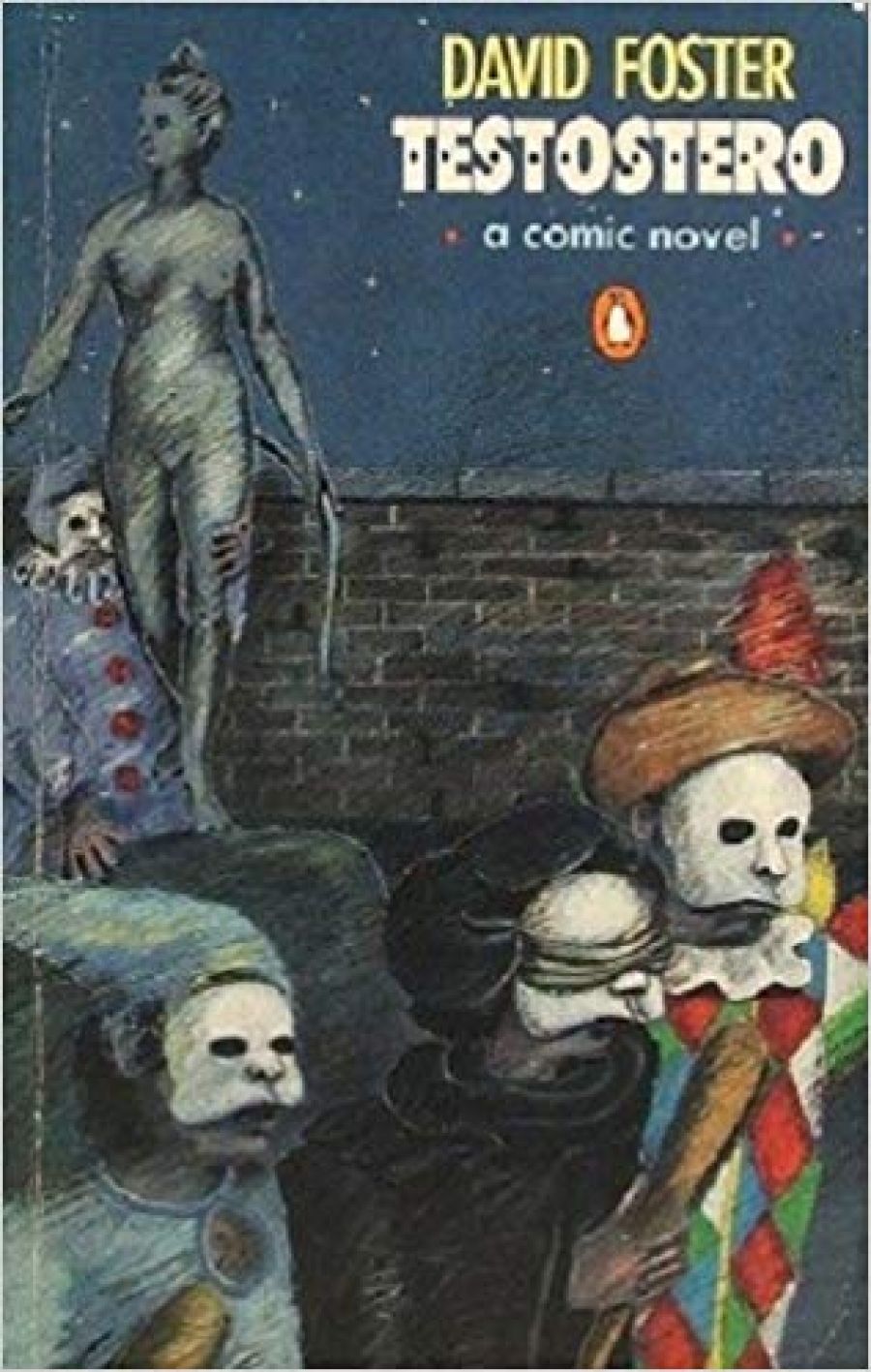

- Book 1 Title: Testostero

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, 188 pp, $8.95 pb

The title of his latest novel, Testostero, alerts us to Foster’s interest in the absurd conjunction of opposites – the reference is to the male sex hormone, with the suggestion of sterility (stero) and fertility, as well as referring to one of the characters (a gondolier turned mafia boss). It is by playing with such opposites, such failures in human logic, that Foster charts his way through the infinite idiocy of human life. In this novel, he gives us Venice/Marrickville, intellectual/physical, academic/clown, homo/hetero and then transsexual.

Moreover, in this novel Foster has found a tradition which can accommodate his peculiar kinds of interest. Testostero deliberately refers to the favourite and familiar comic plot of the separated identical twins. It plunges us into the world of Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors, Goldoni’s The Venetian Twins (and the more recent Nimrod updating of the story) and Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Gondoliers. Of course, these are all plays most appropriately accompanied by comic songs which lift the exchanges into the ridiculous fantasy world where anything can happen in the name of entertainment. Foster is restrained (but only just) by the choice of a novel for a plot which should by rights be accompanied by singing, dancing, cheap stage effects and grand entrances by comically confused nursemaids. The favourite stage trick of this kind of farce – the actor who plays both twins – was the principal interest of the recent British stage thriller Corpse; all the evil of murder is lost as the audience wonders whether the actor will make it backstage and change his jacket in time to enter as the other twin.

Foster enjoys all these references and even pays homage to Tom Stoppard, who shares his passion for the mixture of death and farce, visual play and word play. By the central part of Testostero, Foster has thrown the novel away in order to present a little Stoppard-like interlude, with corpses all over the place. One begins to wonder why he has written a novel at all.

Yet, Foster needs the novel to allow room for his own personality, ever ready to comment on the foibles of his characters and the rest of the world. He begins in Venice with Bernard Hickey masquerading as Perry Patetic, the academic in charge of the Commonwealth Writers’ studio. Noel Horniman, the working-class Australian poet, meets his lookalike Leon Hunnybun, the upper-class English psychologist who would rather be an art critic. After canal adventures they move to London, then Scotland searching for the mystery of their multiple birth. They swap places successfully until Noel’s penchant for reviewing psychology books and Leon’s lack of a bronze medallion (he becomes attendant at the Marrickville pool) catches up with them. Parents, ex-wives, sons, pseudoparents, nurses, appear on all sides until the mystery of Leon’s and Noel’s birth is cleared up in a suitably outrageous fashion.

Foster’s writing is packed with satiric observations about human behaviour, and particularly human thought-patterns, which cannot find their way into the dynamics of dialogue and action in a play. He forces his way into the reader’s mind with endless puns and asides which push us from the concrete into the abstract world. The old tension between the rational and irrational remains, with Leon putting the argument for induction while Noel waits hopefully for intuition. And the rational progress of the novel is broken constantly by sallies into the irrational. In this novel, Foster demonstrates the human capacity for high levels of rational thought and the corresponding commitment to irrational passions, activities and failures.

One obvious reason for Testostero to be written as a novel is that Foster has no company of actors or film production crew, but there are moments when the novel reads like the script outline of a wonderfully funny play where the visual jokes may be at least as important as the verbal ones. For example, in the scene where Noel meets Leon for the first time, Leon is overcome not by this gross image of himself but by Noel’s uncanny likeness to St Peter in Luigi’s Lion Triptych. The scene proceeds entirely in dialogue where the reader must guess who is speaking each line and Foster indulges in some of the oldest jokes of all time. At the same time, he plays the characters against each other with Patetic anxious to please the waiters rather than his guests, Noel’s ex-wife expressing disgust with Cortesana Lottotatz’s leopard-skin coat, Leon being unbearably polite and Noel unbearably vulgar.

Only the alert, visually imaginative reader will pick up everything in a scene like this, and a reader who can read at a pace which will allow even tasteless jokes to pass. Often, too, the jokes are of the kind which would be better enjoyed in a room full of people sharing the silliness. But that may be the nature of all extroverted comic art.

On the other hand, how could a play do something like this?

As Hunnybun presses one of the many buzzers that embellish the marvellous door of Ca’Pantaloni, a blackamoor with a knocker in his teeth starts violently on a floor above, throws open the shutters, and using a convex mirror like that over a blind canal intersection, squints in annoyance at the street below.

The blackamoor is the black American, Colt Cargo, who has been making love to Cortesana upstairs. These verbal tricks are everywhere and they need rereading or they will be overlooked entirely.

As in his earlier novels, Foster asks a lot of his readers. His perfect reader needs to have an imaginative and intellectual range almost as wide as Foster’s own, but even the imperfect reader will find plenty to laugh about in the course of this novel. Essentially, neither the play nor the novel seems an adequate form for Foster’s kind of writing. The words on the page are no more than clues to the games of the mind and the reader’s mind must meet the novel more than half way. It is a compliment to the reader ready for the challenge – you, too, may be as rational and mad as the characters in Foster’s world.

Comments powered by CComment