- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Photography

- Custom Article Title: Helen Grace reviews 'Bill Henson: Photographs' by Bill Henson, introduced by David Malouf

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The silence of Bill Hensen

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In under a decade Bill Henson has managed, by careful and strategic marketing, to become probably Australia’s leading art photographer. This status is based on the precise circulation of three or four exhibitions of work, Untitled Sequence 1979, the Untitled 1980–82 series, the Untitled 1983–84 series, and the Untitled 1985–86 series. The titles indicate a continuity of practice rather than anything else, a statement that the photographer has been engaged throughout this time in producing work. By an economic placement of the work in different commercial and public galleries around the country and in contemporary survey shows, such as the 1981 Perspecta and more significantly, the Australian Bicentennial Perspecta, Henson has managed to maximize the exposure and impact of his work. The Australian Bicentennial Perspecta provides a useful means of circulating the work internationally (the exhibition has been shown in Germany), although Henson, like most of us, does not really need the bicentennial; it simply provides a free trip into the international market in which Henson’s work is already placed by virtue of its content and formal qualities.

- Book 1 Title: Bill Henson: Photographs

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $90.00 hb, 120 pp

The temporal presence of the work, indicated by its title, also covers the work of marketing; Henson’s activity is economic in every sense of the word. No time, no effort is wasted in the process of refinement of a product and the maximisation of its circulation. This is why the dates in the titles of the work provide nothing more than a sense of continuity; Henson does not spend every minute producing photographs, but no time is lost in unproductive activity, nonetheless. The means of display is always part of the work. Robert Rooney, in a review in The Australian, notes that Henson’s work is always carefully shown; lighting of the installation is always considered to heighten the effect; specially constructed partitions are used.

A concern with the presentation of the work is also carried into a desire to control what might be said critically about the work. Since a very critical article by Adrian Martin in Photofile, Henson has refused to have his pictures used in the magazine, even in the review of his work. This too, makes a good business sense …

The publication of a book of the work is inevitable, given the clear focus of Henson’s project. A book of work functions as a sort of mail-order catalogue, taking the work to audiences who may not have seen the photographs in galleries, extending even further the availability of the work, placing in continued circulation a proper name, the name of the artist, Bill Henson. This is another effect of calling a body of work Untitled; in the absence of a name for the photographs, every photograph is ultimately entitled Bill Henson. This is most clearly seen in the series which Henson did for the C.S.R. photographic project. This project, conducted over ten years, engaged most of Australia’s best photographers in an attempt to photographically interpret the corporate entity C.S.R. The project, one of the more interesting instances of corporate engagement in the arts, was begun to commemorate C.S.R.’s centenary in 1978. Whereas photographers like Micky Allan, Sandy Edwards, Gerrit Fokkema, Carolyn Johns, Jon Rhodes, for example, attempted a more critically based portrait, Bill Henson’s work, once again entitled Untitled, succeeded in subverting C.S.R.’s own efforts in corporatizing the work of the other photographers, in a way which the more consciously critical work was ultimately unable to do. Notwithstanding the efforts of a socially concerned photography to be critical of the corporate environment, even this work could be appropriated within the corporate image; each critical photograph finally carries the caption, C.S.R. This is not the case with Henson’s work. We do not finally see another set of C.S.R. photographs; we see only Bill Henson photographs.

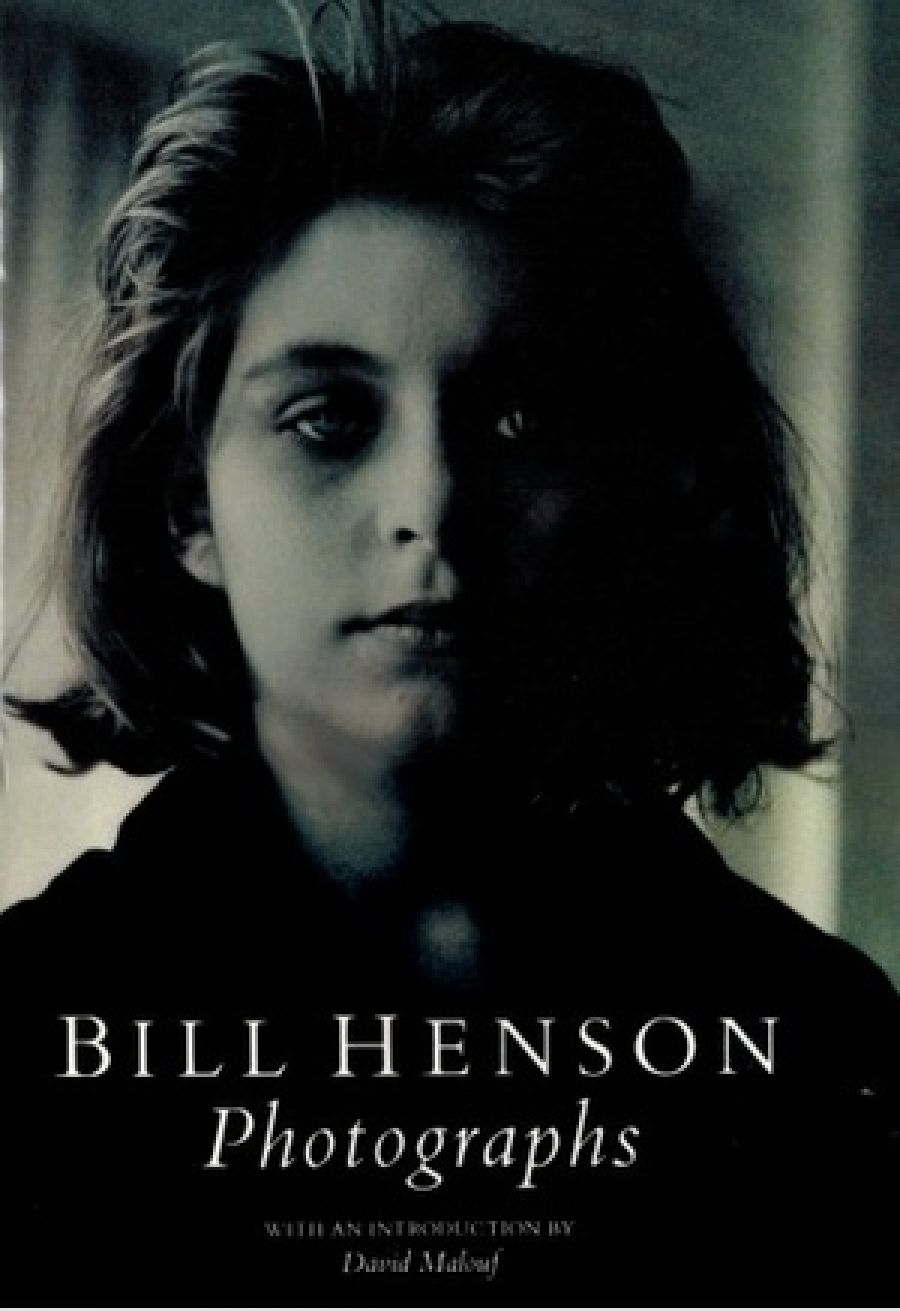

The book, Bill Henson, Photographs is yet another instance of the economy of Henson’s approach, with its clear focus on the proper name. The dust jacket carries a head and shoulders image of a young woman looking blankly at the camera; laid over the blackness of her clothing is a caption in a forty-eight-point, serif face, upper case: ‘Bill Henson’. Below this, in italic upper and low case, the word ‘Photographs’; already less emphasised than the proper name. Below these again, the invocation of another proper name, ‘With an introduction by David Malouf’. The title, Bill Henson: Photographs, is repeated again, twice, before the arrival of the contents; two short written pieces about Henson’s work and two sequences of photographs, the Untitled 1979 series and part of the Untitled 1983–4 series.

In the Untitled 1979 series, a sense of narrative is achieved by the apparent movement of a young boy in between still images of tightly cropped telephoto frames of crowds, almost like surveillance pictures. The photographs are quite cinematic in their neo-realism. Yet it is impossible to say what they are about; they are suggestive of an ‘elsewhere’ (Europe), certainly not ‘here’ (Australia). A wide range of readings might be made of them; the 1981 Perspecta catalogue, for example, attempted to list the possibilities in the breathless language of advertising which promises the consumer everything he or she is looking for and more:

So many nuances and contrasts are threaded into the infinitely varied visual and psychological texture of the work: motion and immobility, naked and clothed, youth and age, the private and erotic resonated against the public and social response, composure and violence, interaction and isolation, vulnerability and withholding, prosaic incident versus monumentality and transcendence.

What Henson gives us is a montage of attractions, which demand our attention, forcing us to look, in an attempt to find a place for ourselves in relation to the images, but there is no place for us; we are as displaced by the images as are the alienated subjects of the images.

The Untitled 1983–4 series is perhaps easier to respond to in that the scenarios of bodily abjection juxtaposed on an environment of architectural excess allow for an immediate response; we are placed in a voyeuristic relation to the naked pubescent subjects; the suggestion of violence is more explicit. These pictures are more discomforting than the earlier series, all the more so because of the distaste of the content. Although (we are led to believe that) we are dealing with the wasted bodies of youthful junkies and the suggestion of the exploitation of children, there is a sense that the photographic process is as much to blame for the exploitation. Henson has refined the structure of juxtaposed oppositions and has aestheticized his subject matter considerably, but the effect which the images produce is still dependent on a crude structure of juxtaposing opulence and poverty, the simplest of oppositions. Whereas a more deliberately political use of these oppositions is no longer permitted to get away with a technique of this kind, art photography can still appropriate the effect without any qualms. These images are probably Henson’s best known, but for me they are his least successful, since they lack any subtlety. The shock value which is achieved on the surface by the subject matter is lost entirely in the context of a now familiar media fascination with abject youth, drugs etc. Henson’s pictures are certainly more beautiful than the bleak, grainy images of anti-drug campaigns, which usually have the opposite of the desired effect. But there is no sense of concern in Henson’s images, only a sense of vicariousness. The images are at times as striking as some of Mapplethorpe’s more confronting work, but Henson, unlike Mapplethorpe, is an outsider in this environment; his concern seems to be more with art than morality in the deliberateness of the sequencing which he employs.

In this book of photographs, we are presented with what are probably some of Henson’s more marketable pictures; his more recent work is far better than the work included here, depending less on crude oppositions and more on a striking photographic technique rather than a content chosen for effect only. His use of colour leaves most other local art photographers for dead. Henson has been more successful than any other Australian photographer in producing a self-consciously artistic photography; but ultimately, art photography’s success can only lie in its capacity to provide illustrations for the marketing, not of a consumable product, but of a proper name, a signature, an artistic persona which is displaced onto finely printed paper in images which remain silent, mute.

Comments powered by CComment