- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Short Stories

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Peter Goldsworthy uses the short story to examine and question elements of the kind of life he leads. There is an attractive lack of pretence in his kind of story; Goldsworthy sketches social situations clearly and succinctly so that he can move on to probe the weaknesses in his characters’ otherwise complacent lives. As the back cover tells us, and the stories reveal, Goldsworthy is a medical practitioner in Adelaide and his fiction is in a tradition which begins with social experience and reflection on it.

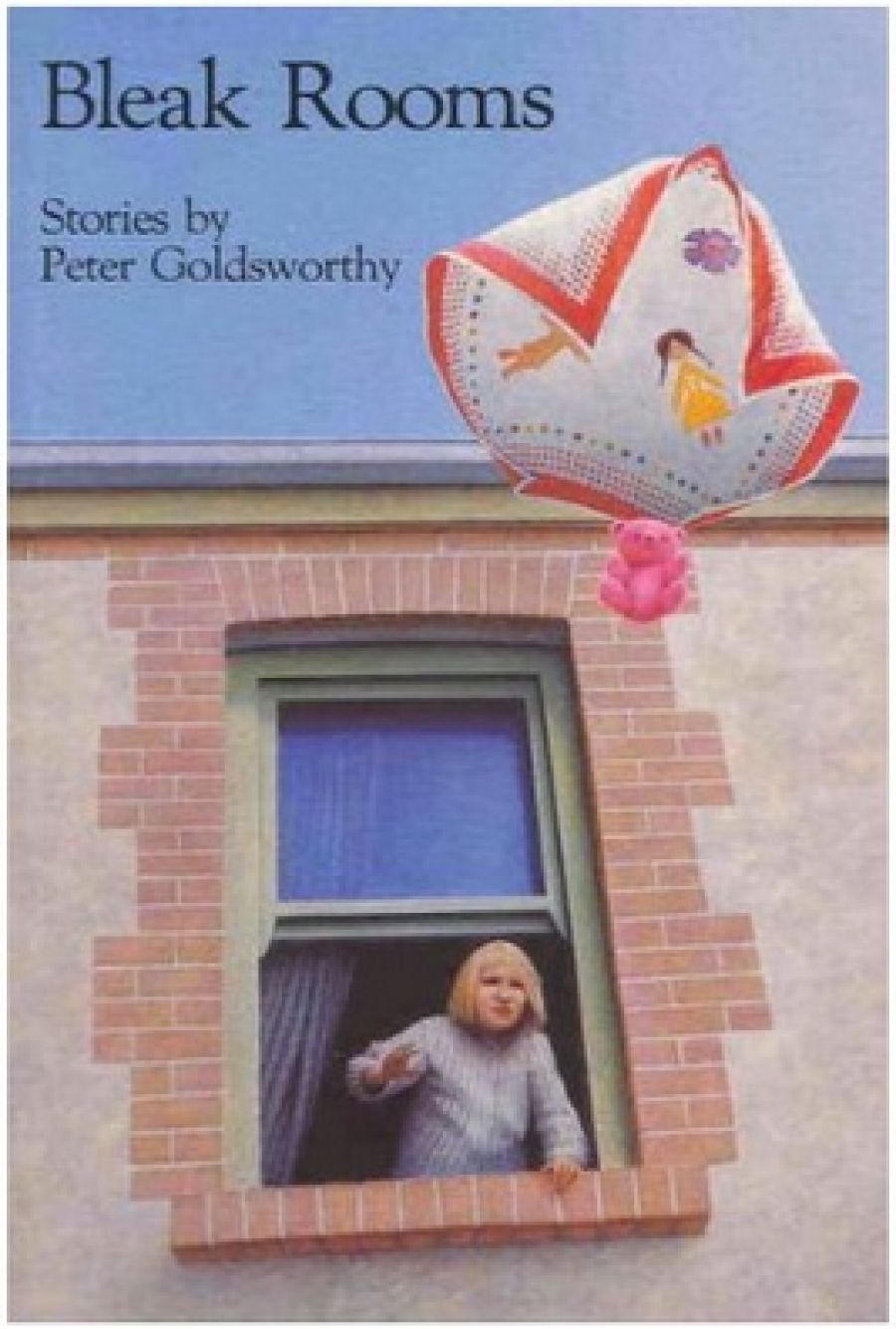

- Book 1 Title: Bleak Rooms

- Book 1 Biblio: Wakefield Press, 137 pp, $12.95 pb

Each of the stories in Bleak Rooms observes relationships familiar to other urban professionals of his generation – sister and brother, mother and son, husband and wife, professional and client, professional and rival. Most of them describe aspects of the life of a general practitioner in suburban Adelaide but it is the practitioner himself, not his clients, whose attitudes are usually questioned. In the story ‘The Affirmative Action Dinner Party’, for example, a doctor invites a hippie leftover from the early 1970s to dinner with his wife and friends. This woman brings out the worst in the group of doctors, as they exchange jokes about their patients and present themselves as deliberately heartless. At the end of the story, the doctor’s wife accuses him of using the woman to make the kind of criticism of his friends which he does not have the courage to make himself. But he admits that he is looking for someone to challenge his own va1ues only to hear an affirmation of those values in the response: ‘You don’t need a stranger to do that ... We’ll tell you you’re full of shit anytime you ask.’

There is a degree of confession and recognition of guilt in the stories, especially in the first story, ‘Requiescat in Pace’. Here, a clever brother feels responsible for his older sister who, in middle age, is trying to throw off her sense of missing out on education, missing out on the freedom to be young and missing out on love or professional success. The story builds up over several small chapters while the sister indulges in the sort of activity which might have been presented as funny. In fact, the figure of the middle-aged woman who leaves her husband and tries to find personal fulfilment through university courses has become a standard subject of satire in Australian fiction. Instead of cheap jokes Goldsworthy manages to tease out the kind of critical and caring relationship between siblings: the brother recognizes his sister’s complaint about her own beauty as the Starlet’s complaint: No-one Takes Me Seriously, the sister admires the brother but cannot find a way to win his admiration. Yet the brother’s pride in his own intellect is undermined in telling ways – his brother-in-law must make an appointment to discuss his marital problems.

In another story, ‘Innocence’, two clever and cynical people observe a seemingly successful marriage from the outside. They are looking for the cracks which experience has taught them to expect but the entertaining game of ‘find the fault’ only heightens the bitterness of their own lives. This pattern of the quick-witted and cynical characters being caught in their own cleverness is repeated several times in the book. Goldsworthy sympathises with the privileged, intelligent, educated professionals – after all, the stories show him to be witty and clever himself -but he exposes the emptiness and directionlessness of lives nourished only by ‘being smart’. Through the book is a strong humanity for those deprived of the intellectual, educational and social advantages the doctors enjoy.

Most of the characters in the stories are called Cassie, Terry, Mandy, Frank, Rich, Jill, Sue, Tony in different combinations so that the book gives the sense of studying a small circle of people in a small city. It comes close to a ‘discontinuous narrative’ in the Moorhouse manner and, as the central character in most stories is a male doctor in his thirties it would not be difficult to arrange the stories as a novel. At the same time, most of the stories reach satisfying endings and manage dialogue very well so that it is tempting to see them as possible television scripts. If only the ABC was in a healthier position Goldsworthy might be able to subvert the Young Doctors–Country Practice–Flying Doctors tradition with the tales of failure within success.

Comments powered by CComment